The Coming of the Chariot

It is thought that the first vehicles of transportation invented were in the arctic north of Europe, where composite wooden sledges were dragged across the frozen tundra by sheer brute strength. The first Middle-Eastern evidence of the use of a vehicle to carry a load comes from the Linear Script of Mesopotamia and our earliest actual example is a sledge found in the royal tomb of Queen Puabi, dating to early dynastic Ur.

When animals were domesticated they began to be used for more than milking or shearing for wool. Their first use in transport was as pack animals and then for drawing these sledges. Later still, solid wooden disc wheels were invented and attached to axles below the heavy sledges.

In time these cumbersome wheels were replaced with lighter (though less durable) composite "cross-bar" wheels, which allowed smaller, lighter carts to be developed. The first wagons were drawn by oxen, but the smaller carts could be harnessed to faster, more manageable animals such as donkeys, mules or even goats.

| |

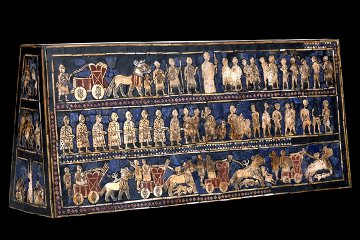

| Early chariots - four-wheeled battle wagons - are depicted on the "Standard of Ur" found by Woolley. |

The advantages in warfare of these small but sturdy transport vehicles quickly became apparent and on the fertile plains of Mesopotamia and Anatolia the precursor to the chariot was created. This earliest form of a military vehicle was a four-wheeled battle-wagon drawn by four asses or ass/onager hybrids. The famous Sumerian "Standard of Ur", now in the British Museum, depicts the driver and a warrior armed with spears and axes riding into battle over the corpses of the slain.

Some warriors and kings were buried with their carts and wagons as well as the draft animals and the drivers. Sir Leonard Woolley uncovered several such burials among the Royal Tombs of Ur.

A later development in Mesopotamia was a type of two-wheeled vehicle whose solitary occupant sat astride a central beam as if riding an animal. However it is likely that the first true chariots were developed on the Eurasian steppes, as shown by the burials discovered along the border between Russia and Kazakhstan, although this is still the subject of scholarly debate.

Radio-carbon dating of horse remains interred with chariots now indicates that this ancient grassland culture, called by archaeologists the Sintashta-Petrovka people, began using chariots around the beginning of the Middle Bronze period, two hundred years before the first evidence of Middle Eastern chariots. (Based on the style of the artifacts found at the burial sites, Russian researchers previously dated the Sintasta chariots to two centuries after the first evidence of chariot use in the Middle East. More accurate radio-carbon testing is required to settle this dispute.)

The chariot quickly became the transport of the elite, whether for war, religion or affairs of state - though the humble donkey remained an important and dignified mode of transport until the introduction of the horse. It was this development that gave the real impetus to the chariot, which now became an even greater weapon, combining high speed, strength, durability and mobility that could not be matched by infantry.

At about the same time the "cross-bar" form of construction gave way to the extremely light spoked-wheel. This gave the chariot even greater speed and manoeuvrability without compromising stability and strength. The number of spokes in the wheel varied from region to region, as did the method of construction, from the very basic slot-and-groove of Assyria, to the sophisticated heat-bent wood of Egypt.

Unfortunately, developments in the chassis and wheels of the chariots were not complemented by developments in the harnessing systems. Horses were attached to the pole of the chariot by yokes in much the same way as oxen and cattle were harnessed to heavier wagons. Until the invention of the bit, the animals drawing the chariot were steered by reigns attached to nose rings!

Much of our knowledge about the design and construction of chariots has come from actual remains interred in the graves and tombs of their owners. In many Bronze Age societies the dead were buried with a rich assortment of grave goods such as food, tools, clothes and weapons - including chariots and their draft animals. Among the treasures found in Tutankhamun's tomb were six chariots that he had used in processions, warfare and for hunting expeditions.

By the 18th Dynasty the chariot had come to dominate land warfare as its potential against the slower foot soldiers came to be realised. Historians tell us that the whole mode of war changed with the introduction of the chariot during the Bronze Age. Infantry were relegated to a supporting role as the chariot spread west from the Middle East into Europe and as far east as India and China.

Before the introduction of the stirrup, bare-backed riders were limited in how they could engage an enemy - they were too easily unseated. Assyrian reliefs show Arab tribesmen seated on camels, one man facing foward to drive the beast while another faced the rear and fired arrows using a short bow. More often horses and other animals were used to transport the warriors to the battlefield, but they then dismounted to fight.

In the 15th century BC, Pharaoh Tutmoses III had over a thousand chariots at his disposal; by 1400 BC the Great King of the Mitanni had amassed several times that number. We can picture these huge numbers of vehicles charging across the plain straight towards the enemy; the psychological impact of such a charge would have been enormous on untrained and unsteady troops.

However the chariots did not actually come to grips with the enemy. Instead, the chariot provided a mobile firing platform for archers who, because they were standing, could handle a longer and more powerful bow. Chariot borne archers could hinder a foe's preparations for battle and deal a deadly blow to his courage and enthusiasm for the fight, while remaining safely out of reach of retaliation. It is not too much to say that the deployment of chariots could turn the tide of a battle, while their use against a fleeing enemy ensured total victory.

The royal chariot formed a mobile command post, giving the king and his generals unprecedented control over their army during the chaos of battle. The chariot also provided a swift means of retreat for the king if the battle should go against him (though the story of Sisera in the Book of Judges records at least one occasion when heavy rain caused the wheels of a commander's chariot to become clogged with mud, forcing him to dismount and flee on foot just like any common soldier.)

Naturally infantry began to adopt new weapons and new tactics to deal with the threat of the chariot. Javelins or throwing spears proved particularly effective, for lightly armed javelin throwers could nimbly avoid the more pondorous chariot while inflicting considerable damage on the vulnerable horses. Against a mixed force of heavy and light infantry, the huge chariot armies of the the Late Bronze age were less successful and by about 1,000 BC the chariot was all but replaced in warfare by mounted cavalry.

However the chariot continued to be used in hunting. The first evidence of its use in this field comes from a Syrian cylinder seal dating to the 18th/17th centuries BC. Beaters on foot flushed out the game which was then pursued and killed by spear-wielding hunters in chariots. Considering that the animals so hunted included lions and wild bulls, the skill of both hunter and driver must have been considerable!

If the ancient accounts are to be believed, the numbers of animals killed in these grand hunting expeditions were staggering. Amenhotep III of Egypt claims to have killed 102 lions in the first ten years of his reign and one particularly successful hunt resulted in a bag of 96 wild cattle. The later Egyptian pharaoh Rameses II went so far as to have a lion tamed and trained to accompany him in his chariot on hunting trips, where it would seek out and chase the prey to within range of the pharaoh's bow.

The final stage for the chariot came in Greece and Rome when wealthy chariot owners entered teams of horses into the races held in the hippodrome. Though the owners of the chariots rarely participated in the actual race - which was a highly dangerous affair - the victory belonged to them alone.

The Athenian politician and general Alcibiades entered seven chariots in the Olympic Games of 416 BC and though we do not know whether he drove any of the chariots himself, we do know that he was awared first, second and fourth places. In 396 BC a team owned and trained by Princess Kyniska of Sparta was victorious and in this case we can be sure that she did not drive the chariot herself: being a woman she was not even permitted to enter the stadium!

By Roman times it was the charioteers who were winning the hearts and minds of the public. The first century AD epitaph of one of the earliest heroes of the sport declares, "I am Scorpus, the glory of the roaring circus, the object of Rome's cheers and her short-lived darling. The Fates, counting not my years but the number of my victories, judged me to be an old man." Having won more than 2,000 races, Scorpus, the darling of Rome, died in the arena.

In the Roman circus there were usually four teams, distinguished by the colours they wore. Over time two of these colours - green and blue - came to dominate and their partisans, much like football supporters of today, were quite capable of rioting in the streets, attacking and killing one another or even deposing a Caesar who failed to please them. Even the mighty Justinian came very close to losing his throne when he upset the all-powerful Blues.

The arrival of the barbarians, however, put an end to the long career of the chariot. Although the Celts of Britain had used the war chariot, it had mainly been as a means of troop transport and the axe-wielding occupants dismounted to fight. The successive waves of invaders from the east who over-ran the Roman empire had long abandoned the chariot in favour of the more manoeuvrable and cheaper cavalry and when they took over the estates of the conquered there was no one left to support the expensive training and grooming of chariot teams.

We do not know when the last chariot race was held, but at its close the sun finally set on nearly four thousand years of history. Today we can only marvel at the elegant simplicity of Tutankhamun's chariots or wonder at the thought of Ahab's thousand chariots plunging into battle. We shall not see their like again.