Egyptian Medicine Revealed

In 1822, the year that Champollion announced that he had deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics, a boy was born in Connecticut in the New World. Little is known about Edwin Smith's childhood; we do know, however, that he became interested in Egypt and its history and in 1861, at the age of 40, he went out to Egypt to see the country for himself.

Naturally, he went down to Luxor to visit the Valley of the Kings and the famous temples, and while there he purchased a number of "antikas", the souvenirs that every tourist (or scholar, for that matter) simply had to take back to his homeland. Among these was a papyrus scroll about fifteen feet long and just over a foot wide which was quite well preserved but which, it was obvious, had lost some portion of its beginning. It was, however, sufficiently important for Smith to record that he purchased it on January 20, 1862 from a dealer by the name of Mustapha Aga.

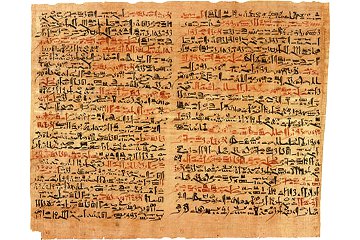

| |

| Two columns from the Edwin Smith medical papyrus. |

Tourism in Egypt then was a much more leisurely occupation than it is now. Today the Diggings tour flies from Cairo to Luxor, usually calling in at Abu Simbel on the way! In Edwin Smith's time, most travellers chartered a dahabiyeh and sailed up the Nile, a journey that could take several months. It is not surprising, then, to learn that two months after purchasing the scroll, Edwin Smith was still in Luxor and the local rascals were beginning to run out of things to sell him. He had already rejected most of their stock and there was a limit to how many tombs could be clandestinely opened and excavated.

In this extremity, the local mafia of antiques sellers put their heads together and came up with a solution. The rather tattered beginning of that scroll was still in their possession but had been removed in order - so they thought - to enhance the price of the rest. They now commissioned a suitable length of papyrus from the local antiques manufacturers, glued the fragments to it and presented the composite to Edwin Smith.

The forgery was clumsy and Smith had no difficulty in seeing through it. However he thought he recognised the fragments and reference to the original scroll convinced him, and so he bought it. Both parties went on their way happily.

Smith, who had dabbled in hieroglyphics, made an attempt at translating the scroll but either he failed miserably or others did not recognise the importance of what they were reading. In either case, the scroll remained in Edwin Smith's possession until his death in 1906.

After his death, Edwin Smith's daughter, Leonora, presented her father's collection to the New York Historical Society and fourteen years later the trustees of that society finally got around to examining the treasure which had fallen into their hands. None of them could read hieroglyphs, so they send the scrolls over to the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute, where they came into the hands of James H. Breasted, the institute's director.

Breasted examined the scroll and translated it, a task that took him ten years. His conclusion was that it was a copy of an ancient manuscript, probably dating from the very earliest period of Egyptian history - between 3,000 and 2,500 BC - but that it had been copied several centuries later by a scribe who had added 69 of his own notes, explaining technical terms or clarifying medical procedures. Unfortunately the scribe had also stopped work abruptly in the middle of a sentence, leaving a good 15.5" of scroll unfilled.

The text of the scroll consists of 48 cases of injury, arranged for easy reference beginning with injuries of the head and then moving down to injuries of the chest and the spine. The most interesting thing about the scroll is that the treatments are all what we might call surgical. There is only one mention of a spell to be recited, a fact which should dispel the common perception that early medicine was all mumbo-jumbo.

Almost equally surprising is the fact that although fractures (even depressed fractures) of the skull are described, there is no mention of the technique of trepanation. We know that many patients went through this rather drastic surgical procedure, where a hole is drilled in the skull. Some even survived it, for the hole in the bone shows clear signs of healing. Although surgeons talk learnedly about relieving pressure on the brain after trauma, sociologists have long suspected that such holes were more likely to be drilled in order to provide an exit route for the evil spirits that caused insanity. The absence of the procedure from this scroll is, perhaps, a support to that suspicion.

This is not to say that all Egyptian medicine was free of superstition. Some of the papyrii are filled with chants and invocations and those who relied upon mumbo-jumbo for their effects were not above claiming esoteric origins and great age as authority for their often dubious cures. The Berlin Medical Papyrus begins with the claim, "Found in ancient writings in a chest containing coduments under the feet of Anubis in Letopolis, in the time of the majesty of King Usephais, deceased; after his death it was brought to the majesty of King Sened, deceased, because of its excellence."

In the same way, the London Medical Papyrus claims, "This book was found in the night, having fallen into the court of the temple in Khemmis, as secret knowledge of this goddess, by the hand of the lector of this temple. Lo, this land was in darkness and the moon shone on every side of this book. It was brought as a marvel to the majesty of King Khufu." Fortunately, both for the ancient Egyptians and for our evaluation of their medical expertise, there are the more "scientific" documents, such as the papyrus we are considering.

Of the 48 cases described by the Edwin Smith Papyrus, four are deep scalp wounds, 11 are skull fractures, ten more deal with other injuries to the head and six deal with spinal injuries. They give us the first description of the brain itself, describing it as "like the corrugations which form on molten copper"; the first description of the meninges or covering of the brain, the first mention of cerebro-spinal fluid and the first mention of aphasia (loss of the ability to talk) due to brain damage.

A typical case is number two.

Instructions concerning a gaping wound in the head which penetrates to the bone.

When you examine a man who has a gaping wound in his head which penetrates to the bone, you should lay your hand upon it and feel the wound. If his skull is uninjured and has no hole in it, then you should say, "He has a gaping wound in his head, an ailment which I will treat."

Bind fresh meat over the wound on the first day using two strips of linen. On following days cover the wound with grease, honey and lint until he recovers.

(Note: "two strips of linen" means two bands of linen arranged over the lips of the gaping wound in order to close it.)

Less promising was case four.

Instructions concerning a gaping wound in the head which penetrates to the bone, splitting it.

When you examine a man who has a gaping wound in his head which penetrates to the bone and splitting his skull, you should lay your hand upon it and feel the wound. If the bone moves and the man shudders violently, if a swelling protrudes through the injury, if he discharges blood from his nose and his ears, if he cannot move his head from side to side or up and down, then you should say, "He has a gaping wound in his head which penetrates to the bone and splits his skull, with a discharge of blood from his nose and ears and stiffness in his neck, an ailment with which I will contend."

Do not bind up the wound, but moor him to his mooring stakes until the period of his injury has passed. He must remain sitting, so make two supports of brick until he reaches the crisis. Apply grease to his head and soften his neck and his shoulders with it.

(Note: "moor him to his mooring stakes" means putting him on his customary diet, without administering to him a prescription.)

The instructions for treatment are interesting. First of all, the doctor is not to apply a tight bandage, for this might distort the skull and in addition cause pressure on the already damaged brain. Secondly the doctor was to massage his neck and shoulders regularly. Thirdly, the scribe who added the notes almost certainly has misinterpreted the phrase "moor him to his mooring stakes". Instead of talking about diet, it may be a reference to the need to immobilise the patient, an interpretation confirmed by the reference to building brick supports to hold the patient upright until he either recovers or dies.

The prescriptions of the papyrus may sound a little strange to modern ears, but they may well be based on sound medicine. After all, the Egyptians had a great reputation as physicians and doctors were held in great esteem in Egypt, as is proved by the proud inscriptions some of them left in their tombs or on stelae. One man, who held the post of "Palace Stomach and Bowel Physician" rejoiced in the twin titles of "One Understanding of the Internal Fluids" and "Guardian of the Anus". In view of the prevalence of tummy-bugs in Egypt, I believe that the Egyptologist who first translated that went around smirking for days!

The Egyptian reputation was quite well deserved. For example, pregnancy testing Egyptian style was to have the woman urinate on a bag containing wheat and barley. If the grain sprouted, the woman was pregnant - and if the wheat sprouted first, she could expect a boy. When this was first discovered, it was regarded as little more than priestly hocus-pocus, but in 1933 some doctors put the method to the test and discovered that it was accurate in 40% of cases, a rate that compares favourably with modern pregnancy testing kits.

It is probable, therefore, that the Edwin Smith Papyrus is based upon good observation, sound common sense and long experience of head wounds, which could be the result of industrial injury or of battles fought with clubs and maces.

The papyrus was positively pessimistic about case eight.

Instructions concerning an injury to the skull under the skin.

If you examine a man whose skull is injured under the skin, with no external sign of injury, you should feel his wound. If there is a swelling under the skin, if his eye is askew on the side of the injury, if while walking he shuffles his foot on the side of the injury, then you should regard him as one who has been injured by something entering from the outside, one whose head cannot freely move, who clenches his fist with his nails in the middle of his palm, who discharges blood from his nose and ears. This is an injury not to be treated.

Cause him to sit upright until he regains his colour and his condition passes the crisis.

(Note: "while walking he shuffles his foot" means that his foot is weak and the sole is turned over while the tips of his toes are contracted into the ball of his foot.)

It is interesting that the papyrus refers to the patient with what is obviously a very severe injury walking! Presumably if a patient was not ambulant, he could not be brought to the doctor and his case was assumed hopeless from the start. Other symptoms noted in cases of head injury include discharge from the eyes, loss of the ability to speak (aphasia), and twitching or shuddering when the wound is touched.

The final case in the papyrus concerns a sprained vertebra - back injuries were probably as common in ancient Egypt as they are today, but perhaps with more reason. Very few workmen today are required to move two ton blocks of stone around by muscle power alone.

Instructions concerning a sprain of a vertebra in the spine.

If you examine a man who has a sprain in a vertebra in his spine, say to him, "Extend your two legs and contract them again". When he extends them both he contracts them immediately because of the pain in his spine. Then you should say, "He has a sprain in the vertebra of his spinal column an ailment which I will treat."

Place him prostrate on his back and make for him . . .

and there the papyrus ends. We shall never know what the Egyptians recommended for back-pain sufferers.