Roman Megaliths

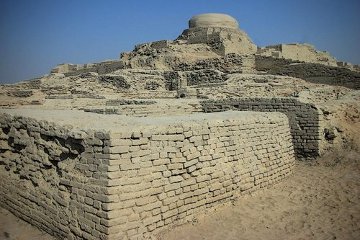

| Mohenjo Daro | 27 19 29.84N 68 08 10.82E | The impressive mound can be clearly seen beside the Indus River, and you can make out the excavations very clearly. |

| Harappa | 30 37 42.67N 72 51 50.18E | The L-shaped mound can be seen, but I presume the excavations have eroded badly, for there is nothing to be seen in the picture, unlike Mohenjo Daro. |

| Arikamedu | 11 54 12.01N 79 49 40.46E | The ancient site of Airkamedu is on the right bank of the Ariyankuppam river, just as it enters the Indian Ocean. Despite proud boasts that this is one of India's foremost archaeological sites, there are no visible remains in the picture and not a single photograph of the archaeological remains. |

| |

| The mudbrick citadel of Mohenjo Daro gives us some idea of the sophistication of this early civilisation. |

The first direct contact between East and West, as far as we know, came when Alexander the Great invaded India and fought a successful battle against King Porus (probably Chandragupta). Like many Westerners since then, Alexander was fascinated by India. The Greek Alexander Romance, which was written within a century or so of his death, describes his meeting with the "naked philosophers" — the Brahmin holy men who wore no clothes but smeared their bodies with ash. They returned clever but evasive answers to the various questions he put to them and impressed the Greeks more by their ascetic lifestyle than with their supposed wisdom, though the Alexander Romance has them predicting Alexander's death at the hands of one of his companions. (Supposedly Alexander was poisoned with a cup of water from the River Styx, a liquid so virulent that it could only be transported in the hollowed out hoof of a female donkey. Presumably it had to be served in the same container, which makes Alexander's unconscious imbibing of the deadly potion rather unlikely. In any case, the first scientific observer to identify the River Styx reports that the water is cold but refreshing.)

The Greeks were even more impressed by the deed done by Calanus, a Brahmin who accompanied Alexander back to Babylon. Plutarch, in his Life of Alexander tells the story.

It was here too that Calanus, who had suffered for some while from a disease of the intestines, asked for a funeral pyre to be made ready for him. He rode up to it on horseback, said a prayer, poured a libation for himself and cut off a lock of hair to throw on the fire. (This probably refers to the single lock of hair which Brahmins keep on their shaven heads - KKD.) Then he climbed onto the pyre, greeted the Macedonians who were present and urged them to make this a day of gaiety and celebration and to drink deep with the king whom, he said, he would soon see in Babylon. With these words he lay down and covered himself. He made no movement as the flames approached him and continued to lie in exactly the same position as at first, and so immolated himself in a manner acceptable to the gods, according to the ancestral custom of the wise men of his country. Many years afterwards an Indian who belonged to the retinue of Augustus Caesar performed the same action in Athens and the so-called Indian's Tomb can be seen there to this day.

From the somewhat breathless tone of Plutarch‘s report we may conclude that as a means of self-advertising, burning oneself alive was highly effective, though in the long run rather self-defeating!

In their turn the Indians seem to have been impressed by the Greek warriors in their bronze armour. The eponymous ancestor of one of the Greek tribes was Javan, a word which, when slightly softened, is the source from which we get "Ionian". The original pronunciation is preserved in the Indian word for soldier — jawan, a word which is still used today and which seems to have entered the language about the time of Alexander.

From the Greek period onwards, trade and contacts between India and Europe increased. Nard, the perfume used by Mary to anoint Jesus' feet, was regarded as "the foremost of perfumes" according to Pliny, while Indian elephants were exhibited in the circus at Rome. The high point of these contacts, from the Roman point of view, was under the reign of Claudias when, according to Pliny, the king of Ceylon sent an ambassador named Rachias (rajah?) to the court of Rome. The alleged reason for this embassy was a shipwrecked sailor who landed in Ceylon and was promptly made a captive. When his pockets were turned out he was found to have a number of gold coins and the natives, eager to know the worth of their prize, promptly weighed them and were impressed to discover that, even though the coins were minted by different kings, they were all the same weight, a fact which was considered to show unusual honesty on the part of the Roman government.

| |

| Somewhere near this beach, Roman galleys and Chinese junks brought the riches of the world to India in exchange for Indian produce such as beads. |

The coin part of the story may well be true, for since 1775 Greek and Roman coins have been discovered on the south and west coasts of India, as well as other objects. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, then Director General of the Indian Antiquities Department, but trained in Britain, was the first to use these artifacts in order to positively date Indian sites. In July 1944 he happened to visit the Madras Museum where he noticed part of an amphora which, his European training told him, had been made about the time Christ was born. He enquired into its source and learned that it had recently been dug up at Arikamedu, a site near Pondicherry, about eighty miles away to the south.

As Sir Mortimer was particularly interested in the question of Indian chronology, he was impatient to go and investigate the site, but at that time the French still maintained a presence in India and it required some diplomatic negotiating for an Indian (British) government official to enter French territory. Once in Pondicherry, however, Sir Mortimer visited the library with its small display of artifacts and immediately recognised several sherds of red-glazed pottery that he knew had been made in the Italian centre of Arretium before AD 45.

The next step, of course, was to visit the actual site and, if possible, conduct some excavations in order to establish which Indian culture was contemporary with — that is to say, came from the same level as — the Italian pottery. It was not until 1945 that Sir Mortimer was able to fulfil his ambition and do some digging at Arikamedu. There he discovered a distinctive type of native pottery which had been made in Arikamedu in imitation of imported ceramics. (Nothing much changes in the East; today the wily Oriental pirates CDs, back then he pirated pottery.) This distinctive pottery was fairly widespread in south India and, of course, enabled Sir Mortimer to date a number of other sites.

It was one of these other sites that provided an intriguing puzzle. The ancient town of Brahmagiri, high in the Deccan, had been a large and prosperous city whose inhabitants were buried in megalithic tombs; that is, huge slabs of rock had been arranged to form a burial chamber or cist, and the whole was then covered with a mound of earth. In most cases the earth had disappeared over the centuries, leaving the megaliths exposed. What made these tombs so interesting was that the cist was entered via a circular hole, rather like a ship's porthole, that had been laboriously hacked into one of the upright stones.

This is such a distinctive feature of the tombs that archaeologists and prehistorians conclude that such tombs were made by one particular tribe or race or, at the very least, by the adherents of a particular religion. These "porthole" tombs are to be found in the Middle East, in north Africa, in Spain and other parts of southern Europe, and even as far west as Britain, where they exist side-by-side with other, more conventional megalithic tombs. In the West, of course, such tombs are dated to prehistoric times but careful excavation at Brahmagiri revealed that the megalithic "porthole" culture lasted well into the first century AD and overlapped the succeeding culture with its imitation Roman pottery.

In fact, Sir Mortimer found evidence for three distinct but overlapping cultures at Brahmagiri. The first was a crude, Stone Age affair whose pottery was made by hand and whose tools were made of polished stone. This Chalcolithic culture lasted until the second century BC and survived by many years the arrival of the Megalithic culture with its different customs and its iron tools and weapons. The Megalithic culture made pots on a slow wheel and, in its turn, survived for a long time the arrival of the Andhra culture, which used the fast wheel to make its imitation pots.

Unfortunately the significance of all this has failed to be appreciated by most archaeologists and historians, who tend to view different cultures as exclusive and progressive. If you find a Chalcolithic site it must, by its very nature, they claim, be older than a Bronze Age site and certainly far older than an Iron Age one. That, however, is a fallacy. Imagine some archaeologist of the year AD 3,000 who goes out to excavate amid the ruins of Alice Springs. In one place he uncovers the ruins of a comfortable brick house complete with piped water and air conditioning. Half a mile away he discovers the evidence for a crude gunyah and camp fire. Obviously, he thinks, the second discovery is hundreds or even thousands of years earlier than the first; yet you and I know that in fact the two are contemporary and that the inhabitant of the gunyah made his beer money by washing the car of the inhabitant of the brick house!

It would be a revolution in historical ideas if all the megalithic monuments were to be dated to classical times instead of to the dim mists of antiquity. It would mean that their creators may well be identifiable with some of the outlandish tribes mentioned by authors such as Herodotus or Pliny instead of being merely "the beaker people" or "the painted-ware people". Unfortunately this concept would require a considerable shake-up in chronology and a major readjustment of thinking in all sorts of fields, which is why such a re-dating is unlikely to be accepted until the evidence is positively overwhelming.

a funeral pyre The awe with which the Greeks and Romans regarded this voluntary self-immolation is probably what lies behind St Paul's comment in 1 Corinthians 13, where he says, "Though I give my body to be burned - if I have not charity it profiteth me nothing." Return