The Tombs of Petra

| |

| The grill in front of the Treasury cover the recently discovered tombs. |

Those who went on our 2004 tour were surprised - as, indeed, we were - to find digging going on in front of the Khazneh in Petra. However once we had peered down the hole and taken a few photographs, we went on our way, little realising the amazing things that were being discovered there.

The excavation was begun mainly as a way of providing employment for the local arabs who, until recently, worked on the excavations at the Garden Tomb (shown and discussed in the film on Petra available from our website). However it did have a serious purpose: over the last few years a lot of work has been done in the Siq, the narrow gorge leading into the heart of Petra, uncovering the original Nabatean paved road that ran along the base of the gorge.

When David Down first visited Petra in 1958 this road was completely covered by debris washed down by centuries of flooding. As we now know, that amounted, in places, to more than twenty feet of gravel and stones. Hidden beneath it were the remains of the watercourse, a succession of altars and betyls or god-boxes, and substantial stretches of paving.

Shortly before the end of the Siq, however, the remains of the paving disappear and it was suspected that it was still buried beneath more flood debris. As, however, this debris provided an appropriate floor for the entrance to the Khazneh, it could only mean that the original Nabatean road had run well below the entrance to the Treasury.

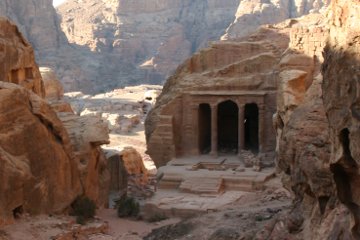

| |

| The recently discovered tombs in front of the Khazneh. |

This, indeed, is what the excavation has shown. The workmen uncovered three classical Nabatean tombs some twenty feet below the modern surface. The facades of the tombs were more or less pristine and, much to the astonishment of the archaeologists, the tombs were found to contain human bones. This must surely settle the long-running controversy over whether the many monuments in Petra were tombs or houses.

Even more fascinating, there was a stone-cut altar in front of the tomb nearest to the Outer Siq and embedded in it were the remains of frankincense!

It has long been known that Petra's prosperity depended upon trade and one of the objects traded was frankincense, brought up from southern Arabia and highly desired by the Greek and Roman world both for personal adornment and for religious ritual. This, however, is the first time that ancient frankincense has been found in Petra.

At the base of the tombs the excavators found traces of the paving that runs through the Siq, confirming that these tombs and the paving are contemporaneous. The archaeologists were keen to clear the entire area and link up the two areas of paving - the Siq and the plaza in front of the Khazneh - but unfortunately funds ran out and the excavation has been filled in again. It is hoped that in 2005 more funds will be available and that the entire area can be cleared.

Where this will leave the Khazneh we are not certain. At the moment the first view of it is the most impressive and memorable sight in Petra (and, indeed, in the whole of Jordan). Whether it will be quite so impressive if it becomes an incongruous facade hanging twenty feet above the plaza, is open to question.

| |

| A line of tombs in the Outer Siq buried deeper by gravel washed down from deforested hills. |

It also raises the interesting question of how these newly discovered tombs came to be buried. We know that the Outer Siq gradually filled with gravel, for in one place there is a line of tombs, each one more deeply buried than the next. Obviously they were not constructed to be buried, but as the floor of the valley rose, so the next tomb was built a little bit higher than its predecessor.

The discovery of the frankincense, however, indicates that at least the first part of the deposition of flood debris must have been very rapid. What is even more remarkable is that the Khazneh was built in the second century AD, since when there has been hardly any flood deposits.

I would attribute this to the effect of man on the environment. The original Nabatean settlers found the Siq more or less free from flood deposits. As Petra grew, so the demand for wood for fuel and building increased until finally the hills around Petra were thoroughly deforested. Eventually, as we are seeing in modern Bangladesh, this deforestation reached a critical point and when heavy rains fell, a devastating series of floods was the result. The first of these washed down vast quantities of loosened soil and gravel, burying the Siq and the plaza at its end, including the altar and its offering of frankincense.

Subsequent floods were less destructive simply because all the loose material had been washed down already and although gravel continued to be deposited, it was also eroded away at about the same rate, meaning that the level in front of the Khazneh remained more or less constant, so when that monument was built, it was constructed at the level of the present-day plaza.

Visitors to Petra today see the tombs as a series of facades, but work done in recent years in the Wadi Farasa has shown that many, if not all, of the tombs were originally constructed with more or less elaborate courtyards in front of them.

Only two of these courtyards survive in any degree: the so-called Urn Tomb in the Outer Siq, which has an enormous vaulted structure approached by steps leading to a colonnaded courtyard; and the Roman Soldier Tomb in the Wadi Farasa, where the foundations of a colonnade can be seen. In this tomb the burial chamber is on one side of the narrow valley and the Triclinium, where ritual feasts may have taken place, is on the other.

| |

| The "Garden Tomb", showing the recently discovered pool in front of it. |

Archaeologists point to the Garden Tomb, just a little further up the valley than the Roman Soldier complex, as another example, but there I fear that I disagree with them.

Unlike the tombs, which have an imposing facade in which there is a doorway leading directly into the tomb chamber, the Garden Tomb comprises a pillared porch and then the doorway and inner chamber. In front of the pillars is a deep pool supplied with water from a purpose-built reservoir. Steps leading down into the pool imply that it was intended for pleasure, not just ornament.

Finally, the inner room has a large window constructed to let light into the room. As it could also let in flies or even carrion birds, this is a most undesirable feature in a tomb chamber and more or less proves that the Garden Tomb was not a tomb but may have been a pleasant place in which to relax.

The only reason I don't call it a triclinium is that it lacks the characteristic benches around the walls (as does the Roman Soldier Triclinium, by the way). However I am by no means convinced that these triclinia were only for funerary feasts.

Little Petra (which also features in the film about Petra available from our website) has three identical triclinia side by side and a fourth directly opposite. This seems to imply either wholly excessive grief (or a very large family of mourners!) or that the triclinia had more mundane purposes, such as the equivalent of a restaurant or cafe.

Indeed, despite the traditional interpretation of the shelves as places where diners could recline, it is entirely possible that these were sleeping platforms and thus the equivalent of lodging houses for Petra's no doubt large itinerant population of traders, camel-drivers and caravan guards.

The recent excavations in the Wadi Farasa have also turned up a number of Christian tombstones from the mediaeval period, which probably belong to the Crusaders or their hangers-on, who were responsible for the small castle on el-Habis in the centre of Petra and the more impressive castle outside the city, which can be seen in the distance from our hotel. Both are shown and discussed in the video.