Interview with Lord Renfrew

Dates continue to be a vital issue in the archaeological world. There are the noisy critics who concede that there is evidence for an exodus from Egypt, the destruction of Jericho, and an invasion of Canaan by a new people, but who insist that this all happened centuries before Israel left Egypt. There are also those who claim that the archaeological dates need revising and then the evidence matches the inscriptional records.

Dr Immanuel Velikovsky was the first scholar to ring the alarm bells in his book "Ages in Chaos" in which he claimed that the early chronology of Egypt and Palestine needs to be reduced by some 600 years. When I was in Israel in May this year I had the opportunity to spend an hour with Shulamit, Velikovsky's daughter. She vigorously defends her father's revised chronology.

| |

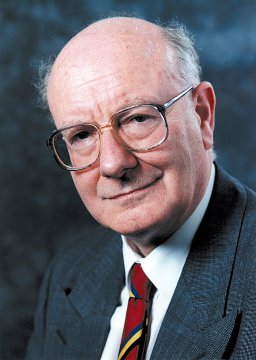

| Professor Lord Colin Renfrew, one of Britain's leading archaeologists. |

While in London a few weeks later I was privileged to spend an hour in the House of Lords with Lord Colin Renfrew. In 1991 Peter James published a book called "Centuries of Darkness". The foreword to this book was written by (then) Professor Renfrew, who is the leading archaeological scholar at Cambridge University. He wrote in part:

"The revolutionary suggestion is made here that the existing chronologies for that crucial phase in human history are in error by several centuries, and that, in consequence, history will have to be rewritten. ... I feel that their critical analysis is right, and that a chronological revolution is on its way."

Centuries of Darkness pp XV, XVI.

Professor Renfrew was promoted to the House of Lords, not because of any family connection but on the merits of his archaeological standing. I was therefore eager to talk to him about his present views. I asked him, "Do you still hold the opinions you expressed in Peter James book?" He assured me that he did and that he presents these views in his lectures.

I consider this development significant in the chronological issue. It means that a revised chronology, challenging the traditional dates of Egyptian history, is no longer a fringe concept promoted by some obscure scholars with few archaeological credentials, but that the revised chronology must be considered a recognised alternative to the traditional dates usually assigned to the dynasties of Egypt and the archaeological ages of Palestine. What is even more significant is that the revised chronology undermines the supposed astronomical certainty of Egyptian dates. The claim that the dates of Egyptian history are astronomically fixed was not based on an ancient eclipse that happened to coincide with some known events of Egyptian history, but on the so-called Sothic cycle, described by David Rohl as "a weird and wonderful thing" (A Test of Time, page 128).

The Sothic Cycle theory was not accepted by all archaeologists, but they went along with it because it was the only basis for claiming any sort of certainty for the dates of Egyptian history. But deduct 350 years from the chronology of Egypt by eliminating the Third Intermediate Period (TIP) and that leaves the Sothic Cycle in a shambles. It means that the dates for the dynasties of Egypt are up for grabs. Scholars can now work on a revised chronology without the restraints of so-called astronomical evidence.

In particular it will free the dating of the Hyksos period from the restrictions of the Sothic Cycle. A period of 150 years is usually assigned to the Hyksos, not on the basis of known lengths of reigns, but simply to squeeze the Hyksos into the Sothic Cycle. The Hyksos can now be assigned a period of some 400 years that enables them to be identified with the Amalekites, wiped out by King Saul of Israel at the end of the period of Joshua and the Judges which lasted for almost 400 years. It will also be closer to the period of 440 years allocated by Eusebius' translation of Manetho.

Truly, a chronological revolution is on its way.

Interview with Professor Lord Colin Renfrew

By David DownDavid Down: You wrote a foreword to the book "Centuries of Darkness" by Peter James in which you said, "This disquieting book draws attention to the very shaky nature of the dating - the whole chronological framework - upon which our current interpretations rest. ... The revolutionary suggestion is made here that the existing chronologies for that crucial phase in human history are in error by several centuries, and that, in consequence, history will have to be rewritten. ... I feel that their critical analysis is right, and that a chronological revolution is on its way." Do you still hold those views?

Colin Renfrew: That applies particularly to the time period around 1000 BC which corresponds with the so-called Dark Age of Greece. But I do believe the chronology is not very secure and I think, strange though it may seem, that the chronology of about 2000 BC is better understood than the chronology around 1000 BC.

DD: What started you? Was it Peter James book that drew your attention to it, or did you already have some ideas about it yourself?

CR: You may be aware that the application of radiocarbon dating, particularly as related to the calibration of dates, had a big impact on European pre-history in general, and it was a great shock to realise that the tombs of Europe were much older than had been thought, so all these changes have taken place, which I think archaeologically are much more significant than adjusting a century or two around 1000 BC. So I don't regard the chronology as less secure than is sometimes claimed around that time. But it did quite rightly educate us that matters were not so well defined as were sometimes believed. I don't think matters have been resolved yet mainly because we still don't know a secure tree ring chronology for that period.

DD: Your book on archaeology is very wide ranging. Is that your specialty?

CR: I am certainly very interested in pre-history and archaeology in general.

DD: Today is a day of specialists. You are rather unique in being so comprehensive. In your lecturing at university you also cover a wide range of subjects.

CR: I have lectured on chronology and I specialise in the Early Bronze Age of Greece and the Aegean, but I think it wise to have a broad view as well.

DD: The major contribution of a revision is that it challenges the theory of the Sothic cycle, because once you challenge that theory you knock the bottom out of the traditional chronology.

CR: I don't know what is wrong with the Sothic cycle in principle. The early Egyptians were keen observers of the astronomical movements. I think the problem lies with the Egyptian king lists and whether they overlap, so it is reasonable to question, particularly during times of trouble, when there were dynastic gaps as to how neat the king lists are. I would not question the basis on which the calculations have been made. When you look at the Early Iron Age of the Aegean you don't have very good links with Egypt to allow you to get hard and fast chronology for the Aegean.

DD: How did you first become interested in archaeology?

CR: I was interested as a child in archaeology. I went to a school in St Albans, which is a wonderful city with rich Roman remains, and by the age of thirteen I had to choose between art and science, so I decided to do science. I was collecting coins by that time and decided to go on an excavation where I met the local archaeologist, and she put me in touch with the archaeologist who was doing excavations. By the time I went to university I decided to switch from natural science to archaeology part 2.

DD: Have you been involved in excavations outside of the UK?

CR: Yes, I was involved in excavations in Greece. If you look at my web site you will find a list of excavations. The web site is called the McDonald Institute.

DD: What is your opinion about Biblical history? Has it influenced you in your observations?

CR: Not really. I soon came to the view that Biblical archaeology was based on texts and that Biblical archaeology did not stand on its own feet. So there was a question as to whether the conclusions should be based on biblical texts or archaeological findings. I think that archaeology should be allowed to speak for itself.

DD: That means your conclusions have not been influenced by a religious viewpoint, but are based on scientific conclusions?

CR: Yes, that is probably so. It is quite possible to be influenced by spirituality or religious thought, without being focused on the archaeology in Palestine. The conclusions drawn are sometimes coloured by religious convictions. In the early days scholars were out to prove the Bible true. From 1859 scholars were emancipated from these restrictive views. By coincidence, this was the year that Darwin published his Origin of Species.

DD: Concerning carbon 14 dating, do you feel it is 100 per cent reliable?

CR: Yes, though it cannot be considered to be absolutely precise and it is not unusual for archaeologists during their excavations to misinterpret their findings, and sometimes archaeologists find that radiocarbon dating is not what they expect. If it is possible to get a stratigraphic sequence of a site by radiocarbon dating, it is of great assistance. I'm afraid there are some archaeological traditions where people don't like things that don't agree with their preconceptions. I don't know of any serious archaeologist who disputes the general validity of radiocarbon dating.

DD: In your University lectures do you deal with the question of chronology? In particular concerning the revision of dates at the time of the TIP?

CR: The revision has taken place. I quite agree with what we said earlier, although we still have to study the details of about 1000 BC. But the broader picture of the overthrow of the diffusionist chronology, and the acceptance of chronology based on radiocarbon dating has been accepted, and that is lectured on not only by me but every lecturer in the University will say those things.

DD: As an alternative view do you think?

CR: No, but as what is now regarded as correct. I don't think that any lecturer in a pre-history department in the universities of the world would not urge following the radiocarbon chronology

DD: Yes, but I am talking about the elimination of the TIP?

CR: Well, we'll get back to details of what is worrying you in the Near East. I think you will find that almost any archaeologist would say that the way to solve such a problem is to get well stratified samples for radiocarbon dating. There is a problem when you try to use radiocarbon dating to solve a matter down to just a hundred or two hundred years. There are some areas where it gets a bit wiggly and that means in practice that sometimes there are some patches where radiocarbon dating is quite precise, but there are other patches where it is sometimes hard to decide within a few hundred years to appoint a single date for what the right answer is. So there are some areas where radiocarbon dating does not solve all your problems, but there are other areas where it does, and that is what needs to be done for the area around 1000 BC.

DD: What would be the attitude of University lecturers to Peter James book?

CR: I think there will be two views. Many would think that he was too sweeping, but there are one or two like myself who think it a very good idea and throws things open for discussion, as he has done.

DD: Thank you.

© David Down 2004