Thera and Poiseidon

A cruise through the blue waters of the Aegean must surely be one of the most relaxing ways of spending a holiday. The gleaming white ship cutting through the waves, the shoals of flying fish scuttering over the sunlit water, the white islands topped with green that dot the sea, the warm sunshine and, for those with a feeling for such things, the sense of history that pervades this part of the world as Cos, Lesbos, Crete, Rhodes and Salamis float serenely by.

| |

| The cliffs at Santorini are the inner walls of a volcanic crater! |

It comes as somewhat of a shock, therefore, when the ship sails into the sheltered waters of Thera, a vast circle of cliffs in the centre of which is a low, smoking island. Incredibly, the ship approaches ever closer to the cliffs, to tie up to a jetty only yards away from the sheer rock walls and a swarm of donkeymen arrive with their mounts to take the visitor up the zig-zag track to the tiny village whose white houses cling to the edge of the precipice.

If you were interested enough to attend the onboard evening lecture arranged by the cruise company, you will have learned something about the amazing history of Santorini. Around 1,600 BC Santorini was one of the larger islands in the Aegean, part of the wide-spread Minoan empire. The gentle slopes that led up to the central summit were covered with vineyards or golden fields of grain, basking under the gentle Mediterranean sun.

The first hints of disaster came when Poiseidon, the Earth-shaker, stirred beneath the ocean and a series of shocks toppled walls on Santorini. The warnings were ignored. The dead were buried, mourned and forgotten and life continued, richer and more comfortable than before. Then the shocks came again, closer together and more violent than before. Cracks opened up in the earth, springs dried up and dull rumblings sounded beneath the ground. Had the people been equipped with the necessary precision instruments, they would have discovered that the summit of the island was now higher above sea level, as the ground beneath them swelled under an intolerable pressure.

| |

| Minoan-style frescoes from buried houses on Santorini. |

We do not know whether there was anyone on Thera when the final cataclysm came, or whether they had taken heed of the warnings and fled in their ships, scudding white-winged across the sea to take refuge in Crete. Probably there were several days when rocks erupted from the volcano and ash rained down, covering the houses and fields beneath 30 to 100 feet of volcanic ash. Then, with an apalling blast of sound, the whole island burst apart; the central cavity collapsed, an ocean of water poured in on top of white-hot rock and turned instantly to steam. Our planet was to know nothing like it until Krakatoa erupted a century ago.

A tidal wave, unleashed by the explosion, raced across the Mediterranean and struck with cataclysmic force at exposed ports and harbours. It smashed the ships on which the Minoan empire depended, surged high up the coasts of Crete and reached out watery fingers for the palaces of Knossos. After that, there was silence. New peoples came in, the Dorians and Achaeans rose to prominence and Greek ships took the place of Minoan in trade and battle and found refuge from stormy seas in the huge natural harbour that Santorini had become.

It is only in the last forty years that this story has been unravelled. Geologists slowly recognised that the neighbouring islands of Thera and Antithera were linked, the remains of a larger island that had been blown apart by a volcanic eruption. The circle of quiet water ringed by cliffs was recognised as the remains of an ancient caldera and the unusually fertile soil of the outer slopes as the product of a volcano. Even then, perhaps, the full scale of the event was not appreciated.

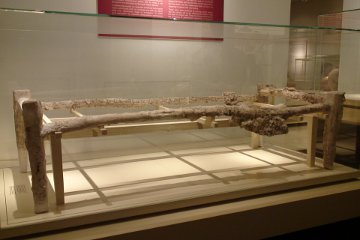

| |

| A bed frame found in one of the buried houses on Santorini. |

Meanwhile survey ships were exploring the bottom of the sea, perhaps in search of oil. Drill cores revealed a layer of volcanic ash covering the sea floor in a huge oval stretching south-east from Santorini, the direction of the prevailing winds.

Professor Marinatos, a Greek archaeologist, began to dig in the ash on Santorini, convinced that the eruption had taken place in historical times and that there must be evidence beneath the ash. Despite the mockery and opposition of colleagues, he dug deeper and deeper and finally, forty feet of sterile ash later, he found the remains of buildings and the usual archaeological debris - broken pots, lost jewellery, discarded tools. He also found frescoed walls, decorated in the distinctive Minoan style, conclusive evidence of the date of Thera's destruction.

The initial date given for the eruption of Santorini was mid-fifteenth century BC - in other words, about 1450 BC. This was sufficiently close to another better known event to cause quite respectable scientists to speculate on the possibility of a link. Particularly suggestive was the ninth of the ten Plagues of Egypt, when darkness prevailed on the land for three days, a thick darkness that could be felt. A dense cloud of volcanic ash would certainly produce just such a darkness and the marine evidence pointed towards just such a cloud heading in the direction of Egypt.

Seismic disturbances could account for the change in colour of the Nile, which in turn could cause the frogs to leave the water. Their death from dehydration would certainly encourage a swarm of flies, which in turn would bring disease to man and animal. Disturbances to the upper atmosphere could be responsible for the unseasonal storms that brought thunder and hail to Egypt, or brought about changes in the wind patterns, carrying locusts from the normal breeding grounds. Even the "crossing of the Red Sea" - assuming a northern route for the Exodus - might have been brought about by the sea receding prior to its thunderous return as a tsunami.

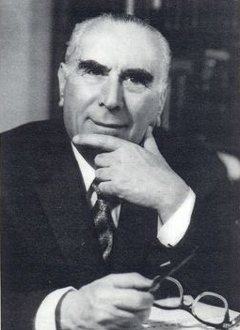

| |

| Professor Spiridon Marinatos, the Greek archaeologist who pioneered excavations on Santorini. |

Now it should be noted that Digging Up the Past does not necessarily subscribe to this interpretation, but neither do we reject it. God is quite as capable of working through nature as of doing miracles against nature. We simply report what scientists and archaeologists are saying and it is gratifying to find the Exodus story being taken as a serious historical record for once.

Now scientists in Israel are claiming a dramatic new confirmation of the Biblical story. Dr Johannes van der Plicht of the University of Groningen's Centre for Isotope Research, in Holland, has teamed up with his fellow-countryman Dr Hendrik J. Bruins, Ben Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, to re-examine carbonised grain found in the ruins of Jericho. The results of their study were announced in a letter to the editor of Nature, a prestigious journal of scientific affairs.

They examined six samples of grain discovered during the excavations at Tel es-Sultan, the site of ancient Jericho. The grain was found on a level that was dated by its pottery to the end of the Middle Bronze age: MB-IIc to be exact. Using the latest techniques of radio-carbon dating, they found that the six samples gave an average age of 3311 (±8 years). The significance of this average, however, is that the ages were very closely grouped, which means that there is very little doubt concerning the accuracy of this figure.

As we has often remarked, the widespread destruction of Middle Bronze sites in Palestine is a mystery, and Doctors van der Plicht and Bruins are aware of this fact. To underline this point they actually quote a passage from The Archæology of Ancient Israel by R. Gonen:

"The causes of the destruction of the Middle Bronze sites have not been adequately clarified. ... In any case, hardly a site escaped massive destruction."

R. Gonen, The Archaeology of Ancient Israel, Yale University Press, 1992, p. 211, 257

Knowing of the link sometimes made between the Exodus and the events on Santorini, the two scientists then tested two samples found at Akrotiri, one of the sites affected by the eruption of Thera. They came up with an age of 3356 (±18 years), which is just 45 years earlier than the destruction of Jericho. It is significant, they claim, that according to the Biblical account, the invasion of Palestine took place forty years after the Children of Israel left Egypt.

On the face of it, the earlier figure would give a date of around 1315 BC for the Exodus, which would be compatible with the idea, held by many scholars, that the Exodus took place under Rameses II sometime around 1300 BC. The trouble is that this is definitely not Middle Bronze!

We have long pointed out that radio-carbon "ages" are merely indications of relative age and should not be taken as statements of absolute age, and it would seem that the Dutch doctors agree. They talk about a mid-fifteenth century BC "wobble" and inform us that, on the grounds of dendrochronology, the Santorini explosion has been dated to 1628 BC. If we accept this date — but also accept the relative dating disclosed by the work of van der Plicht and Bruins — then we can put the Exodus in that same year and the destruction of Jericho to approximately 1583 BC.

Of course, not all scholars agree with these latest findings and some, including experts from the Palestine Exploration Fund, have hastened to oppose them, so it promises to be a lively debate. We will keep you up to date with further developments of this story as they come to hand. Perhaps, however, we can let the Dutch have the last word:

"Although they are powerful tools, archaeology and pottery are not the sole avenues that can be used to unravel the human past. Environmental events, high precision radio-carbon dating and precise regional dendrochronologies may provide information unobtainable through archaeological associations."

Nature p. 214

Note: Dendrochronology is the science of counting tree rings and in theory has the potential to be as accurate as nature itself. As a tree passes through life it experiences events that affect its growth patterns — drought or forest fire, for example, which produce little growth and thin rings, and abundant rain and warmth, which would produce much growth and thick rings. Scientists attempt to match the patterns in trees of different ages and thus extend their count backwards in time.

Unfortunately trees are as varied as people and you cannot guarantee that your samples will all come from the same species of tree or from the same position on the trunk. It can sometimes be a matter of opinion whether the sequence "thick thick thin thin thick" in one tree matches the sequence "thin thin very thin very thin thin", in another. Even worse is the fact that a tree on one side of a mountain may exhibit very different patterns to an identical tree on the other side of the mountain, which was in the rain-shadow and near a village full of careless children who were always setting the bush on fire. This is why the good doctors emphasise the need for "precise regional dendro-chronologies."

Dendrochronology is a useful tool, but a lot more work needs to be done before it can live up to the claims that are being made for it.