Sellotape and Scrolls

The art of archaeological restoration is, to the public, an arcane process of gluing together ancient pots or filling in the missing bits of broken statues. One thinks, for example, of the restorers using strips of sellotape to gently lift away the marks of the oil-stained hammer used by a maniac to smash Michaelangelo's Pieta. Less happy results using the same medium were observed during our recent tour of the Middle East.

| |

| We saw this lady in the Rockerfeller Museum removing Sellotape from the scrolls. |

Our excvation that year was at the famous Western Wall of the temple mount in Jerusalem and as a reward for our exertions we were taken on a guided tour of the basement of the Rockerfeller Museum. Among the mysterious crates and dusty archives two things stand out: the lively and fascinating talk given by Joe Zias, and the sight of a deft fingered lady, armed with tweezers and a camel's hair brush, working on the famous Dead Sea scrolls.

Naturally we were curious to know what she was doing: we had visions of pioneering work uniting hitherto separated fragements of unknown documents but the reality was rather different. A somewhat shame-faced curator explained that when the scrolls were originally found they were laid face-down on sheets of glass and then secured in place with copious quantities of sticky tape.

Now, as anyone who has tried to repair a book with Sellotape will be aware, everything is fine to begin with. Months or years later, however, you return to the book to discover that the "sticky" has dried out and a strip of yellow plastic peels away, leaving behind a hard, yellow powder that is indissolubly welded to the paper. (More recent tapes claim to be free from this defect, but we are talking 1948, not 1997.) This is what had happened to the Dead Sea Scrolls and the unfortunate damsel with the tweezers was engaged in removing the tape and as much of its remains as possible and then remounting the precious parchment between two layers of fine nylon mesh.

| |

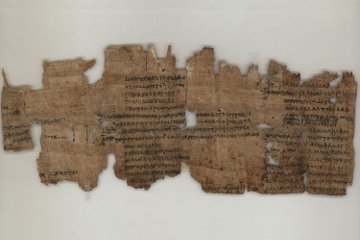

| Tabtunis Papyrus693, the sole surviving fragment from one of Sophocles' plays, "Inachus". |

Unfortunately, as the Egyptologists of the University of California at Berkley have discovered, modern materials have their own problems. The university holds what may well be the most important collection of ancient scrolls in America — an archive of Egyptian papyrii found at the ancient site of Teptunis. The scrolls, which date between 300 BC and AD 300, were discovered wrapped around or stuffed inside a hoard of mummified sacred crocodiles. They were acquired by the university in the 1930s and the experts of the time, determined to do their best for these precious documents, mounted them between sheets of clear acrylic. No doubt they felt that the risk of damage from dropping the sandwich and breaking the more usual glass had been lessened.

What they did not realise — indeed, what no one realised in those heady days when plastic was the miracle of the future instead of the curse of the present — was that this supposedly inert substance leads an active life of its own. As most housewives now know, cling-film emits various nasty chemicals that evaporate from its surface. What most housewives don‘t know is that all plastics, to a greater or lesser degree, give off various volataile substances. Not only are these substances toxic or corrosive or otherwise harmful, but their absence alters the chemical structure of the plastic, causing it to disintegrate.

This is what has happened to the plastic-wrapped papyrii of Berkeley. Not only has the plastic started to crumble and discolour, but alert-eyed Anthony Bliss, curator of rare books and manuscripts, has noticed that the various chemicals given off by the plastic have started to damage the scrolls. It has become urgent that the precious papyrus be removed from the plastic and mounted in the more orthodox glass, a task, you might think, well within the capabilities of anyone with two brain cells and a modicum of manual dexterity.

Alas, life is never that simple. Plastic, as you may have observed, is a great attractor of static electricity. You may even have amused yourself by laying a sheet of plastic on a couple of books and rubbing it with a silk handkerchief, thereby causing the tissue-paper dolls you have thoughtfully positioned beneath to "dance". (It never looked like dancing to me, but then, of course, I date from before the era of discos and raves.) Similar scientific delight can be obtained by rubbing a nylon comb on a wool suit and then passing it above the hairs of your arm.

To the horror of the conservators, the double sheets of plastic have built up a quite substantial charge of static electricity, sufficiently strong to cause the papyrus fragments to cling tenaciously to the plastic. Sod's Law being what it is, it was inevitable that half the fragment would cling to one sheet of plastic and the second half to the other. Two thousand three hundred year old papyrus having lost a good deal of its flexibility, the result was that one fragment became two (or more) and Anthony Bliss lost a good deal of both hair and sleep.

Fortunately hi-tech, having created the problem, was able to come up with a solution. Silicon chip manufacturers, of whom there are one or two in California, also have problems with static electricity. Unwanted discharges are quite powerful enough to blow the sensitive circuits on modern chips such as the Pentium, causing it to come up with ever more eccentric answers to the question "2+2=?" Hobbyists working at home deal with the problem by means of an earth strap, one end of which you clip around your wrist and the other end to a convenient water pipe. In the large factories of southern California the preferred method is to have a special fan that blows a constant stream of ionised air over the assembly line.

Ion Systems, manufacturers of these fans, have donated a sample of their merchandise to the harrassed academics and bliss is once more ful. (In case you miss the pun, I thought I would mention that the single 'L' is deliberate.) As he explains, "When you open the plastic sandwich, the ionised air gets in, neutralises the static charge and the papyrus drops free."

In gratitude, Berkeley University intends to go modern and place images of the scrolls on the Internet. Roger Bagnall, of Columbia University in New York, is overseeing the project as he has already placed a large number of other scrolls on-line. Those with both interest and equipment can view them at the Centre for Tebtunis Papyrii.