Immortal Utnapishtim

| Bahrain mound field | 26 08 46.91N 50 30 43.07E | You will have to zoom in close to make out the mounds. Every one of those "pimples" is a mound of sand and stones covering a grave. There are two things to note: the first is the total lack of photographs, indicating the attitude of the Bahraini authorities towards this national treasure; the second is the encroaching houses which have destroyed vast areas of the mound fields. |

| Barbar Temple | 26 13 34.49N 50 29 02.50E | It is difficult to makeout the dun-coloured temple against the dun-coloured soil around it and the picture is not clear enough to allow the discerning of any features. |

| Falaika Island | 29 27 58.33N 48 17 19.58E | The pointer is over the site of al-Khidr, which was surveyed by the Kuwaiti-Slovak Archaeological Mission. The Bronze Age mound can be seen on the shore to the east of the large rectangular shape which is part of a modern Muslim cemetery. |

The discovery of the Gilgamesh Epic is one of the most dramatic stories in the romantic and exciting history of archaeology. Young George Smith, an engraver by trade, became interested in archaeology and spent all his spare time in the British Museum, where he taught himself to read cuneiform. There he was spotted by Henry Rawlinson, the man who deciphered cuneiform, who arranged for him to be employed by the museum on the task of translating the clay tablets and inscribed stone monuments that had been discovered in Mesopotamia.

| |

| George Smith, the young man who discovered the Epic of Gilgamesh. |

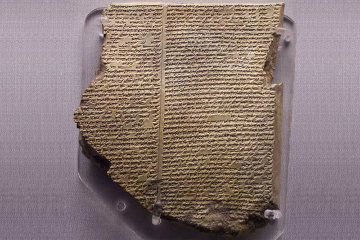

One day, as young George was hard at work on the often boring task of translating the ancient equivalent of till receipts, he came across a broken tablet that told a remarkable tale of a man named Utnapishtim, who had been the sole survivor of a flood sent by the gods. Warned by one of the gods, Utnapishtim had built a boat, filled it with food and a selection of animals, and then sailed across the flood-waters to a triumphal landing on Mount Nisir. There he sent out a selection of birds to ensure that the waters were gone before venturing out of his refuge.

The parallels with the Biblical story of Noah and the Ark were unmistakable and immediately caught the attention of the world's press. Scholars made the not unnatural mistake of declaring that this was the origin of the Biblical tale - instead of seeing it as independent confirmation for the Bible story - which only roused public interest to a higher pitch.

Unfortunately the tablet was broken and only half the story was there. In the hope of finding more Biblical parallels, the Daily Telegraph newspaper offered George Smith £10,000 to go out to Nineveh and find the missing half of the tablet. Compared with this, hunting for needles in haystacks would be no more than a pleasant Sunday afternoon occupation, but in happy ignorance young Smith accepted and set out for Mesopotamia. In a sequel so astonishing as to almost justify the term "miraculous", within a week of starting to dig Smith had found the missing half and was on his way back to Britain!

| |

| The "Flood Tablet" from the Gilgamesh Epic series. |

Unfortunately for the Daily Telegraph, the tablets that George Smith brought back with him, although undoubtedly related to the original story, had no further parallels with Biblical history. Instead they contained a fabulous tale of the adventures of Gilgamesh, the mythical king of Erech, the first romance known to history.

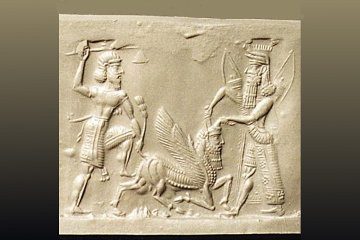

In essence, the story runs like this: Gilgamesh was king of Erech and rather too big for his boots, so the gods let loose a wild man, part human and part beast, to trouble him. After several attempts to capture this creature, whose name was Enkidu, Gilgamesh had recourse to a stratagem. Instead of the usual bait he had been using, he sent out a prostitute to wait by the waterhole. Enkidu, entranced by the woman's wiles, fell asleep in her arms and was promptly led back to Erech in triumph.

Once there, however, Gigamesh and Enkidu became fast friends and often went out hunting. Together they hunted down a fabulous wild bull sent by the goddess Ishtar, but on one of these expeditions Enkidu was wounded and died. Distraught over the loss of his companion, Gilgamesh fell to thinking about life and death and for the first time the realisation of his own mortality was borne in upon him. He determined to devote the rest of his life to seeking for immortality.

| |

| Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the Bull of Heaven: a seal impression from Mesopotamia. |

Somehow he learned of Utnapishtim, who was immortal, and journeyed to the far off land of Dilmun to visit him. There Utnapishtim explained that immortality was a special gift from the gods, granted to him as recompense for all he had gone through in the flood - which is why he tells the story of the flood that George Smith first translated.

Mankind had become too numerous and noisy and kept annoying the gods, so they decided to wipe man out. However Enki, the gold of the waters under the world, the primaeval Apsu (from which our word "abyss" is descended), warned Utnapishtim and advised him on how to escape the flood. After the week-long flood and the cautious sending out of the birds, Utnapishtim left the ark and offered a sacrifice to the gods who, realising that by destroying mankind they had cut off their source of sustenance, "clustered round the sacrifice like flies". Enki interceded for Utnapishtim and Enlil, the great god, went aboard the ark and touched Mr and Mrs Utnapishtim on their foreheads.

"Hitherto has Utnapishtim been mortal. Now shall he and his wife be like the gods and they shal dwell in the distance at the mouth of the rivers."

Of course, Utnapishtim pointed out, Gilgamesh could hardly expect the gods to arrange another flood just so that he could become immortal. Seeing how cast down his guest was, however, he mentioned another possibility. In the waters beneath Dilmun - possibly in the waters of the Abyss which could be reached beneath the sea - there grew a certain plant whose flowers gave immortality. The problem lay in how to reach this underwater plant.

Gilgamesh was equal to the situation. He tied rocks to his legs and jumped overboard. Sure enough, at the very bottom of the sea, he found the precious flower, plucked it and returned triumphantly to dry land, where he promptly set out for home, to share the magic with the elders of his city. Alas, on the way back he was overcome with tiredness and lay down to sleep by a pool of water. While he slept a snake crept up and swallowed the flower of immortality. Which is why snakes live forever: whenever they get old they just shed their skins and get a new lease of life. The moral of the story seems to be that if mankind cannot conquer sleep, how can they hope to conquer death?

In all the excitement over this sometimes bawdy and often rambustious tale, no one noticed the almost casual mention of Dilmun. There had been a few other references to this country: for example, in the series of tablets selected by Rawlinson and published by the British Museum, two tablets in the second volume mention Dilmun, as do two in the third volume and another two in the fourth volume. All the references were obscure and three, which were fragments of hymns or incantations, simply mentioned Dilmun in conjunction with one or another of the gods. As a result many scholars came to regard Dilmun as a mythical land, the equivalent of the Isle of Avalon or Valhalla.

This belief was strengthened following the excavation of Nippur by the University of Pennsylvania in 1899 and 1900. At the foot of the ziggurat the archaeologists discovered 35,000 tablets, nearly all of them written in Sumerian, rather than Akkadian. In view of the number of tablets found, it is not surprising that one broken tablet was put aside for fourteen years. Only in 1914 was this particular tablet translated and then it was found to be the Sumerian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, even older than the Akkadian tablets translated by George Smith. In them the hero of the flood story is called Ziusudra, but the outline of the story remains the same.

"Anu and Enlil cherished Ziusudra, the king, the preserver of the name of vegetation and of the seed of mankind. In the land of crossing, the land of Dilmun, the place where the sun rises, they caused him to dwell."

Another tablet, a large one containing 278 lines of cuneiform arranged in six columns, is now in the museum of the University of Pennsylvania. It is a long, mythological poem known to us today as Enki and Nikhursag. The author sings in praise of these two gods, but principally of Enki, the god of the Apsu. According to Sumerian belief, the earth floated on the waters of the Abyss. Unlike the insignificant seas of this world, the primaeval waters were fresh. They were separated from the ordinary sea water by the bed of the sea, a point which will become significant as our story proceeds.

The first discovered historical reference to Dilmun came from Sargon's boastful account of his campaign against Merodach Baladan of Babylon, the king who sent ambassadors to King Hezekiah. After describing how he chased Merodach Baladan all the way down to southern Iraq, Sargon says:

"I brought under my sway Bit-Iakin on the shore of the Bitter Sea, as far as the border of Dilmun. Uperi, king of Dilmun, whose abode is situated like a fish, thirty double-hours away in the midst of the sea of the rising sun, heard of the might of my sovereignty and sent his gifts."

Since then a number of other references to Dilmun have been found. The earliest is a tablet of Ur-nanshe, king of Lagash in southern Mesopotamia. This king, who lived about 2520 BC records in one of his inscriptions that "ships of Dilmun, from the foreign lands brought me wood as a tribute." The last reference is from the eleventh year of Nabonidus, 544 BC, last king of Babylon, who mentions a "governor of Dilmun".

Opinion swung in favour of the idea that Dilmun was a real, historical country, though possibly, like modern Arabia, it was a centre of religious worship and pilgrimmage. The trouble was that no one knew where Dilmun could be, apart from the vague references to it being in the direction of the rising sun, "thirty double-days" (walk or sail?) away from the head of the Persian Gulf. Some opinion favoured the recently discovered Indus Valley civilisation uncovered by Sir Mortimer Wheeler at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, though other ancient references seemed more likely to refer to them.

| |

| A mound field on Bahrain. Notice the giant mound in the background on the right. |

Matters remained in this pleasant uncertainty until the 1950's when Geoffrey Bibby began to excavate on the island of Bahrain in the Persian Gulf. He was first attracted to the site by the enormous "fields" of mounds scattered all over the island. There were over 170,000 of these mounds, most of them eight or ten feet high and about twelve feet in diameter. Some, however, around the village of A'ali, were twenty or thirty feet high and correspondingly large.

The vast number of these mounds interested Bibby, for there was no way that Bahrain itself could ever have accommodated such a large population. The sheer number indicated that Bahrain was a popular place of burial - and that in turn implied that Bahrain had a special religious significance, rather like Ynys Enlli, the island of 10,000 saints off the Lleyn Peninsular in north Wales.

Bibby was not the first to excavate on Bahrain. For years the local inhabitants had been "excavating" the mounds in search of building materials for roads and houses. It was thus well known that the mounds were burial sites, for each one housed a skeleton or two together with an assortment of grave goods - a pot or two, a few useless trinkets, occasionally a bronze spearhead or battle-axe - not enough to make large-scale grave robbery an interesting proposition in the humid heat of the Persian Gulf.

Although Bibby was the first to conduct scientific excavations, he did not turn up anything substantially new among the grave mounds and after a time repetition began to pall. He therefore turned to a couple of other locations that a preliminary survey had identified as possible archaeological sites and almost immediately began to make important architectural finds. These, as he remarks in his book, Looking for Dilmun, were a mixed blessing.

"I have heard it said, by serious-minded archaeologists, that the perfect excavation would be one in which nothing at all was found. I can see what they mean. Certainly structures are a nuisance. Build a wall and you will make a foundation for it first; you will dig a trench to put your foundation in and when you dig a trench you will mix up the contents of a level older than you with the contents of the level you yourself lay down, and thus the stratigraphy is disturbed. Sure enough, sooner or later someone else will dig a hole through your level to salvage the stones you used for your wall and use them in one of his, and the stratigraphy will be disturbed again. Anyway, it is hard work for an archaeologist to remove a wall and if it is an important building, like our Islamic fort or P.V.'s 'palace' or the Barbar temple, you try not to remove the walls and before you know where you are, you have no room to dig down further and examine the stratigraphy underneath."

Geoffrey Bibby, Looking for Dilmun, p. 103

| |

| Stones to which sacrifices were tethered in the Barbar temple. They look to me more like anchors or mooring stones! |

It was the Barbar temple that proved particularly interesting. This site, which is a short distance south-west of Bahrain's capital of Manama, had been occupied since the earliest days of Mesopotamian civilisation. The temple revealed three levels of construction, the earliest of which showed distinct architectural affinities to the temples of al-Ubaid and Kafajah in southern Iraq.

Despite the fact that each of the three temples on the site had been built to a different orientation, they all shared a common feature: a deep pit approached by steps from the temple. The rectangular pit, constructed from beautifully cut stones, was in fact a pool of sweet water; it represented the Apsu, the Waters of Chaos, the dwelling place of Enki. The temple is believed to have been dedicated to Enki and Ninkhursag.

This discovery led Professor Bibby to think a little bit more about Bahrain itself. Due to certain peculiarities in the geology of the neighbourhood, Bahrain island is plentifully supplied with fresh water springs, a number of which occur off-shore. Some of these off-shore springs are so powerful that it is possible, if you know exactly where they are, to anchor in what appears to be open sea, drop a bucket over the side and bring up fresh water!

In other words, Bahrain is a place in very close contact with the Abyss, a place where the wall between Earth and Apsu is very thin indeed. The name of the island - Bahrain - is Arabic for "two seas"; could one of these be the natural sea and the other the hidden, mythical sea of Chaos?

Was it possible, then, that Bahrain might be the legendary Land of Dilmun? There were a number of indications that this might be so. In the first place, the burials in the mounds contained many copper and bronze implements. Tablets found in Ur and elsewhere referred to a copper trade with Dilmun. For example, a certain Ea-nasir, who lived about 1800 BC, wrote a bitter letter of complaint to another trader.

"When you came you said, 'I will give good ingots to Gimil-sin.' That is what you said, but you have not done so. You offered bad ingots to my messenger saying, 'Take it or leave it.' Who am I that you should treat me so contemptuously? Are we not both gentlemen? Who is there among the Dilmun traders who has acted against me in this way?"

Geoffrey Bibby, Looking for Dilmun, p. 188

Ea-nasir is mentioned in another tablet where a shipment of copper, weighed out "according to the standard of Dilmun" is described. From this we learn that the shipment was nearly nineteen metric tons, an extremely valuable cargo even by today's prices! The tablets make it clear that the copper originated elsewhere, but was trans-shipped (and possibly processed) in Dilmun. That would certainly fit Bahrain, where there are no mines but which has long been a centre of trade.

A less certain indication comes from the fact that Bahraini pearl divers, like Gilgamesh, have traditionally fastened stones to their feet to enable them to descend to the sea-floor, a practice that has only recently been discontinued in favour of more modern methods.

There is, however, another fascinating link with Dilmun. In the Quran the story is told of how Moses met with "one of God's servants" at "the meeting place of the two seas" - and the Arabic for "two seas" is Bahrain. Shortly after Mohammed died, his followers collected together everything they could recollect about him and his teachings. Among the things commented on is this meeting, and in the Recollections it is explicitly stated that the "servant of God" was al-Khidr, the Green Man.

Now al-Khidr has a shrine on the nearby island of Falaika, erected for the saint's convenience. He spends most of his time at Kerbala in Iraq, a holy city for Shi'a Muslims, but every Tuesday he is supposed to fly to Mecca, resting Tuesday night in the Falaika shrine. Furthermore, legend states that al-Khidr had formerly been the vizier of Dhu'l-Qurnain and had drunk from the Fountain of Life and is therefore immortal.

"Now Dhu'l-Qurnain, the 'One with Two Horns', is the usual epithet among the Arabs for Alexander the Great, perhaps because Alexander was often represented with the rays of the sun surrounding his head. But if the Qur'an is here claiming that Moses met the vizier of Alexander the Great, something is seriously wrong with its chronology, for Alexander lived nearly a thousand years later than Moses. Can Dhu'l-Qurnain be some other horned entity? If so, there are many claimants. The Babylonians and Sumerians consistently represent their gods with horns or with horned helmets. Gilgamesh is generally represented as horned, while he travelled in the early portion of his epic journeys together with a being, Enkidu, who was not merely horned, but was half bull and half man. In that connection it is worthy of note that immediately following the quotation from the Sura of the Cave the Qur'an goes on to tell of Dhu'l-Qurnain, that he travelled to the setting of the sun and then to the rising of the sun, where he built a wall of brass as a defense against the giants Gog and Magog, and this is very reminiscent of the travels of Gilgamesh and his bull-man companion. But if Dhu'l-Qurnain is Gilgamesh or Enkidu or a Babylonian god, who then is al-Khidr? That he achieved immortality suggests strongly that he might be identical with Utnapishtim/Ziusudra."

Geoffrey Bibby, Looking for Dilmun, p. 260

There was one final, curious discovery that may shed light on this question. At a place called Qala'at al-Bahrain, Bibby and his team excavated a large building of uncertain purpose that they called a palace for want of a better description. At one level they excavated a floor and, like good archaeologists, they swept and brushed it meticulously. When they stood back to admire their work a keen-eyed member of the team noticed that there were a number of circular patches on the floor, where the soil was of a different consistency and a slightly lighter colour.

Careful probing with a trowl revealed that a bowl had been buried upside down in a pit dug to receive it. The dirt was cleared away and the bowl carefully lifted out. To the archaeologists' astonishment it then appeared that the upside down bowl was merely the lid to another bowl, right side up and filled with clean sand. The other circular patches disclosed the same curiosity: two bowls, filled with sand and buried mouth to mouth.

As the afternoon breeze was starting to blow and whip up the dust, the bowls were carefully carried back to base camp and there, using camel-hair brushes and teaspoons, the archaeologists slowly and carefully removed the sand. In seven of the bowls they found the neatly coiled skeleton of a snake!

Furthermore, in four of the bowls they found a small turquoise bead set in among the snake's bones. In a fifth they found a pearl, in the remaining two nothing, but pearl dissolves easily when buried and it is possible that damp may have somehow leaked into these bowls, causing their pearls to disappear. In other words, someone had carefully buried dead snakes beneath the floor of this building and had placed at least one pearl - possibly more - and turquoise beads in with the snakes before filling the bowls with clean sand.

Things are buried beneath floors for one of two reasons: either that is the most convenient way of disposing of them, or there are religious reasons. Snakes that have been killed because they were raiding the fowl pen are usually thrown out on the rubbish heap: they are certainly not buried with honour beneath the floor. It follows, therefore, that these snakes had been buried as part of a religious ritual.

But why snakes? An object buried beneath a house is intended to either act as guardian of the house or to ensure good luck and prosperity to the house and its occupants - sometimes both. You will remember that, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, it was the snake that ended up swallowing the Flower of Immortality. Is it possible that the "flower" that Gilgamesh retrieved from the seabed was none other than a pearl? (In which case, Bibby concludes, the turquoise beads were a poor man's equivalent of the pearl, which even in those days were regarded as valuable.)

| |

| Bahrain is a chaotic jumble of old and new, wealth and poverty. |

Back in 1996 I visited Bahrain. The Gulf Air jet flew over hundreds of miles of dry, empty sand and mountains that looked as though they had been torn and sculpted by water in the distant past, before it swooped down over the sea and came into land beside the gleaming white buildings of Manama. The heat and humidity, as I came off the plane, had to be experienced to be believed!

The Bahraini officials were polite and obliging, but somewhat less than helpful. The tourist office was full of information about duty-free goods, cheap pearls and exotic night-life, but seemed totally ignorant about burial mounds. The girl did not even have a map of Bahrain to give me - though she could have sold me a map of Manama with all the nightclubs and pearl emporia marked. She did, however, direct me to a neighbouring office where I was presented with the "Bahrain Official Pocket Guide" and there I found a picture of the famous burial mounds.

I hastened back to the tourist office and showed the picture to the girl. She was none the wiser, but she did recognise the name of the village - A'ali - and was able to indicate that it was a considerable distance to the south of Manama. It was, she said, a good hour away by car. Mark Twain's wry comment about a country that employed similar units of measurement came to mind: "In this country when a man goes to a tailor he asks for trousers that are two seconds long in the leg and half a second round the waist."

In the event the hotel receptionist was more helpful. He not only gave more explicit directions but, after showing me to my room, came up with a scruffy individual who owned a broken down car and would, for a consideration, take me to A'ali. A quarter of an hour later we rattled round a bend and drew up beside the famous mound field.

A huge rectangle, perhaps three-quarters of a mile by half a mile, was crammed full of the mounds, so close that they actually touched each other. The ground was covered with flakes of stone and these, it seemed, had been gathered together and heaped up to form the hundreds of mounds. I climbed the nearest, dashed the sweat out of my eyes and raised my camera.

On the other side of the field I could see a couple of huge mounds towering over the lesser ones that filled the intervening distance. The owner of the dilapidated car obligingly took me round to see them. The first one we came to had been sheared virtually in half and the base further undermined by a sort of man-made cave. I could not help but look askance at the nearby factories and buildings, but at the same time it was interesting to see the stratigraphical evidence of how the mound had been built up.

Other huge mounds, also badly damaged by road-making and tomb robbing, were surrounded and almost hidden by neat new buildings, but at least they were protected by wire-mesh fences. A fourth lacked such protection and the cavity at the top where grave robbers had been at work was half-filled with rubbish of all sorts. There is a reconstructed mound in the modern museum not far from the airport, but one cannot help but feel that the Bahraini authorities could do more to protect and publicise the originals.

From there we travelled to the Barbar temple. A large sign in English and Arabic gave a precis of the history and significance of the site and the caretaker, a migrant worker from India who came scurrying out of the corrugated iron shed beside the entrance, was most obliging. He accompanied me around the ruin, pointing out the Apsu pit, the remains of the altar and three pierced stones that, he indicated, were for tethering the sacrificial animals. His commentary was somewhat uncertain, for he spoke no English and we had to rely on signs and the few Arabic words I recognised.

He constantly referred to an illustrated guidebook, which was only in Arabic and of which he only had a single copy. I think he said that I could buy my own at the museum but I will never know, for when we went to visit the museum it was shut for the siesta - traditional in this heat but somewhat unnecessary for an airconditioned building - and did not open again until shortly before my plane left.

As the Gulf Air jet climbed into the blissfull coolness of the upper atmosphere, I fell to thinking about Gilgamesh and Geoffrey Bibby. Most legends have a basis in fact or their echoes can be found somewhere in history. Was it possible, I asked myself, that there could be some historical or factual basis for the romance of Gilgamesh and Utnapishtim?

Of course there is the flood story. When George Smith first came across the broken tablets of the Gilgamesh Epic it was, perhaps, reasonable to think that, because they were so much older than the Bible that they might be the origin of the Biblical story of Noah and the Ark. Since then, however, anthropologists have found so many flood legends, most of which bear more than a passing resemblance to the story found in the book of Genesis, that it is far more reasonable to suppose that all these legends and stories are based upon a common folk memory of a single cataclysmic event.

But what about that curious insistence in both the Akkadian and the Sumerian versions of the Epic, that Utnapishtim (or Ziusudra) was granted immortality as a compensation for what he had gone through? Is it possible that there is some basis in reality for this feature of the story?

According to the Bible, men lived to extraordinary ages in the days before the Flood, with Methuselah, at 969 years, heading the longevity stakes. This is paralleled by the Sumerian king-lists, which attribute thousands of years to the kings "before the flood". There are those who would assign both sources to the realm of fantasy; that is not my concern here.

In Genesis chapter 11, however, much more believeable ages are given to the post-diluvian patriarchs - with one notable exception: Shem, the survivor of the Flood. Using the data given in that chapter, it is quite simple to draw up a time line from which we can see that the average length of life grew progressively shorter throughout this period, with the consequence that, with the exception of Eber, no-one, up until the time of Isaac, outlived Shem.

Generation after generation passed away, and each succeeding generation asked the same question of those who travelled to Shem's home to visit him. "How is the old man?"

Always the same answer was returned: "Oh, he's still there. Still the same, doesn't look a day older."

For ten generations it must have seemed that Shem was immortal, a fitting figure to be the prototype of Utnapishtim in the Gilgamesh Epic.