Egg Tempera and Fayyum Portraits

The British Museum has recently put on an exhibition called Ancient Faces, a display of the funerary portraits discovered by Sir Flinders Petrie at Hawwara. During the years since the portraits were discovered, they have been scattered to museums all over the world, but in its exhibition the British Museum has assembled nearly two hundred, many on display together for the first time ever.

Traditionally, Egyptian dead were carefully wrapped in elaborate bandages, often wound around each individual finger and toe! Over the head was placed a mask that, at least in stylised form, was intended to represent the features of the deceased. Tutankhamun had a golden mask; less prominent persons had to make do with masks of stiffened linen decorated with paint.

Around about the first century AD, as prosperity increased under the pax Romana and more people could afford the full Egyptian funeral, all this individual attention became just too much for the undertakers of Egypt. To try and cope with the rush — and, no doubt, to try and reduce expenses — they latched onto the idea of mass production, turning out thousands of identical coffins very similar to the ones still in use today. The body was wrapped in a simple shroud held in place by a few bandages.

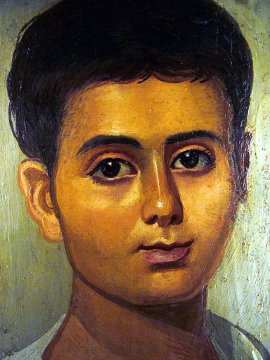

| |

| A Faiyyum Portrait of a boyo or young man. |

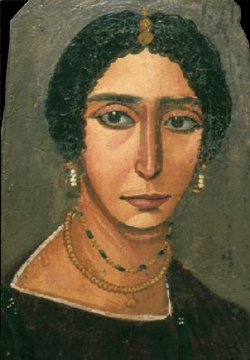

In order to preserve the individuality of the deceased, however, a flat slab of lime or oak wood was placed over the face and on it was painted a portrait of the dead person. These portraits are stunning in their life-likeness: naturalistic colours shade expertly into one another and in place of the wooden formality of previous ages, these people are depicted with vivid, lively expressions that reveal the character as well as the features of the dear departed. A young man has a direct, bold stare above a curving, humorous mouth. An elderly woman has turned-down, petulant lips and forehead creased in a permanent frown.

There are several controversies surrounding these portraits, however. The liveliness and naturalism of the paintings leads some to claim that they were made while the subjects were still alive. On the other hand, eight CAT scans conducted by the British Museum show a close correlation between the age of the person in the coffin and the apparent age shown in the picture. As predicting one's own age at death is a rare skill, it is possible therefore that the portraits were painted after death and it was the skill of the artist that brought the dead face to life.

A second controversy surrounds the technique used by the ancient artists. Tiny fragments of paint from the pictures have been analysed chemically, as have the contents of a mixing saucer. These tests show that the artist used pigments of red and white lead which were not known until after the Roman occupation in 27 BC. On other grounds we can put an end date of around AD 200 for the pictures, yet the majority of the portraits were painted using a technique known as egg tempera, which was not to surface again until the Renaissance, a thousand years later.

| |

| A Faiyyum Portrait of a somewhat severe-looking woman |

The great problem for artists has always been keeping the colour on the canvas: you go to a great deal of trouble to grind up your yellow ochre or crimson lake, you mix the powder with water and paint a beautiful picture and then, five minutes after the paint has dried a puff of wind comes along and blows all the powder away, leaving you with a blank canvas! In order to fix the pigment to the surface, therefore, a variety of agents have been used and one of them is egg yolk. You might have thought that this would give all the colours an unhealthy yellow tint, but in fact the quantities of yolk involved are very small, a single egg supplying enough yolk for quite a large canvas.

It may be coincidence, but art suppliers Daler-Rowney have just launched a range of ready-mixed egg tempera colours. A starter pack of six 22ml tubes in basic colours represents a substantial saving on the cost of the individual colours. Unfortunately the recipe they use only dates back to 1906, but art restorers have found the Daler-Rowney quite satisfactory, so if there are any budding artists out there who want to carry on the tradition of the Egyptians, fork out and have a go!