Colourful Marble

On the recent Digging Up the Past tour of Greece and Italy I was amused at the regularity with which our guides in Greece started to harangue us on the subject of the Elgin Marbles. The first time or two I let it go, having no particular axe to grind in the matter, but when the third guide started on the familiar harangue I argued back - which disclosed the other amusing thing.

One or two of the guides became quite agitated that someone dared to disagree with the divine right of the Greeks to demand back something they had sold, the others just shrugged and got on with talking about something else. Clearly there was some instruction from above about the matter and they themselves were less fanatical about it.

One of the issues raised by the guides who were really upset over the subject was the matter of the "cleaning" of the stautes, when one of the curators of the British Museum took wire brushes and mild acid to the Marbles in order to clean the "discolouration" off them. In fact, we now suspect that the "discolouration" was the remnants of the brilliant colours with which the Marbles - as with all ancient Greek and Roman statues - had been painted.

Alas, there was a doctinaire attitude about at the time which declared that the Greeks had only worked in "pure" white marble and, ancient references to painting notwithstanding, anything else was heresy.

Of course, this "cleaning", however misguided or even damaging, is not to be compared with the total destruction of the Marbles in a lime kiln, which may otherwise have been their fate if Lord Elgin had not rescued them at great personal cost, but it does show the danger of allowing theory to take precedence over evidence - in any field.

Today we know that Greek statues were painted, and not just in the pastel colours which we saw in the Archaeological Museum in Athens, colours which had faded considerably after two and a half thousand years exposed to the fierce sunlight of Greece or Italy. The colours were brilliant - vibrant even - as Dr Vinzenz Brinkmann is able to attest.

| |

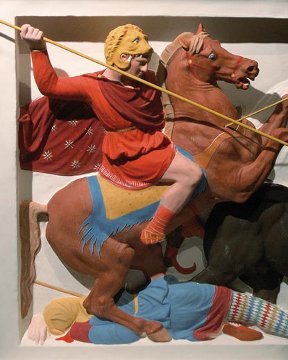

| This is how the Alexander Sacrophagus may have looked originally if Dr Brinkmann is correct. |

For the last twenty years Dr Brinkmann has been researching the subject of the paints used on ancient sculptures. He employed a variety of techniques, including polarised light microscopy, x-ray fluorescence, diffraction analysis and infrared spectrascopy. As a result he can tell us that red and yellow came from ochre clays, bright red was mercury sulfide cinnabar, blue came from copper carbonates azurite, green from malachite, and copper calcium silicate provided a synthetic blue known as Egyptian Blue. White was either lead or lime, purple of course came from murex shellfish, and black, curiously enough, was not lamp-black but carbonised bone!

He has chosen to make the results of his research public in a very dramatic manner: an exhibition of copies of Greek sculptures he has studied, painted in the original colours. Entitled "Gods in Colour", the exhibition consists of some twenty full-size reconstructions painted in their original colours, along with thirty-five original statues and reliefs from the collection of the Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptotek of Munich.

One of the reconstructions is part of the pediment from the Temple of Aphaia on the island of Aegina. The original was excavated in 1811 and acquired by King Ludwig of Bavaria. It must be particularly pleasing for Dr Brinkmann to include this art work, for it was this pediment that first demonstrated the Greek art was not the "pure" white marble that is found today.

| |

| The same scene on the Alexander Sarcophagus as it appears today. |

In the museum at Delphi we saw some reliefs from the Siphnian Treasury, but these were plain stone in the "classical" manner. A copy of part of these reliefs, brightly painted, is in Dr Brinkmann's exhibition, together with a technicolour Alexander Sarcophagus - we have seen the plain white original in the Archaeology Museum in Istanbul.

ancient references One of the clearest of these references comes in a play by the Greek author Euripides, where he has Helen of Troy lament the war between the Greeks and the Trojans and wails:

The quote implies two things: the first is that statues were commonly coloured or painted; the second is that the paints were not as permanent as the Greeks might have hoped. Those exposed to the weather probably needed frequent touching up if they were to remain in pristine condition! ReturnMy life and fortunes are a monstrosity,

Partly because of Hera, partly because of my beauty.

If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect

The way you would wipe colour off a statue.