Archaeology and the Bible

The Early Church

The Earliest Remains

| |

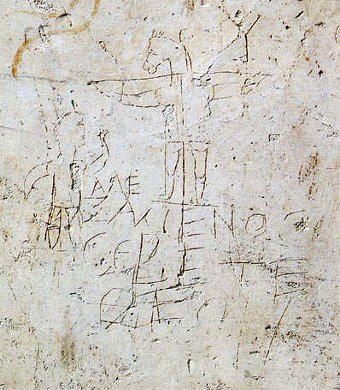

| A satirical bit of graffiti with a Christian meaning. |

There was a common rumour in the ancient world that the Jews worshipped an ass. Cornelius Tacitus, in the fifth book of his History states that when the Jews were wandering in the desert following the Exodus, they suffered lack of water and were guided to a pool of water by wild asses and therefore worship the beast. This graffito clearly indicates that the unknown Alexamenos is worshipping a Jewish deity who was crucified - and this can only be a reference to Jesus, a Jew Who was crucified and also worshipped as God.

A more enigmatic reference to Christianity is the SATOR square. First found scratched into wall plaster in Pompeii, the square is made up of five five-letter words arranged so that it reads the same top to bottom or bottom to top, forwards or backwards, horizontally or vertically.

SATOR

AREPO

TENET

OPERA

ROTAS

The actual words make little sense: SATOR means "sower" or "originator" and may be understood more generally as "farmer"; there is no such word as AREPO, so it may be an invented name for someone, though others have suggested that it is a misspelling of "arrepo", which means "I creep towards"; TENET is "to hold" or "to keep" or even "to own"; OPERA simply means "work"; ROTAS is a "wheel" or something which whirls around such as a whirlwind. If the word is linked to "farmer", the connection may be that some ancient ploughs had wheels.

Putting them all together doesn't make an awful lot of sense: "Arepo the farmer owns wheels for work" (other interpretations are possible). Despite this lack of meaning, the square has been found all over the place, from Corinium (modern Cirencester) and Manchester in Britain to Dura Europus on Rome's eastern frontier. There are even three examples, written in runes, from Scandinavia!

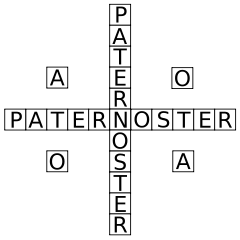

| |

| A possible use of the Sator Square as an anagram. |

The most convincing explanation for the square is that the letters can be rearranged to form the word PATERNOSTER (Our Father, the opening words of the Lord's Prayer) twice, arranged as a cross. There are four letters left over - two 'A' and two 'O' - which may be understood as representing the Greek alpha and omega, a reference to Christ, Who introduces Himself in Revelation as "the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End."

I wonder, however, whether the meaning may be deeper than that. God is the creator or originator - SATOR. In Ezekiel chapter 1 the prophet sees God's throne carried on cherubim, one of whose noteworthy features was the "wheels within wheels" that were under their control. AREPO could be a form of the verb "arepus", which would make it "by means of". A very loose translation could then be, "The Creator by means of possessing and operating the wheels".

More likely, however, it was never intended to be a complete sentence. Another well-known Christian word is ICHTHUS (fish) whose five Greek letters were intended to stand for significant words, but not a complete sentence.

I esous (Jesus)

CH ristos (Messiah)

TH eos (God)

U ios (Son)

S oter (Saviour>

In a time of persecution you might idly draw a simple fish with your finger and see if the person to whom you were talking recognised the symbol. To be sure, you might ask him what it meant and expect the explanation as a sort of password. The Sator square might have served a similar purpose: it was not a complete sentence but each word had a meaning associated with it.

Documents

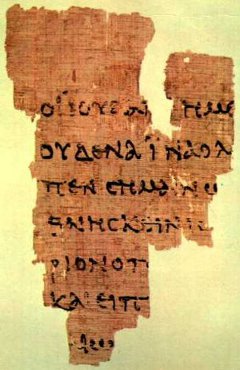

| |

| The John Rylands Papyrus 457, otherwise known as P52. |

The fragment is written on both sides, which might indicate that it was a page out of a book. The words don't make much sense on their own - for example, the words on the front of the fragment spell out "the Jews for us ... anyone so that the w... oke signifyin... die en... rium p... and sai... Jews". Fortunately Professor Roberts was familiar with the Bible and after a bit of searching realised that the words came from the Greek of St John's gospel. He was able to arrange the words, together with the missing ones, to make a reasonably-sized page with appropriate line-lengths. The text of the front then reads:

the Jews, "For us it is not permitted to kill

anyone," so that the word of Jesus might be fulfilled, which he sp

oke signifying what kind of death he was going to

die. Entered therefore again into the Praeto

rium Pilate and summoned Jesus

and said to him, "Thou art king of the

Jews?"

Of course, in English the lines are of wildly differing lengths, but in Greek the line lengths are approximately equal. The only exception is the second line on the back of the fragment where the words "for this" (eis touto) simply cannot fit and have probably dropped out through scribal error because the same words occur on the previous line!

Which brings us to the point that the person who wrote this papyrus was clearly not a professional scribe. The writing appears slow and laboured, in several instances the writer has had to go over letters because his pen was running out of ink the first time, and in one place he writes the letter 'a' in an entirely different way to everywhere else in the fragment! It would seem that the author was an educated person doing his best to copy something he values because for some reason a professional scribe was not available - and a possible reason is that a professional might have betrayed him to the authorities!

Professor Roberts compared the style of handwriting to other papyrii that could be dated and concluded that it had been written during the time of Hadrian, probably between AD 117 and AD 138. This sort of analysis is very subjective and the document may have been written any time between AD 100 and AD 150. In fact, the closest dateable document was P.Berol 6845 which is dated to AD 100. (See Wikipedia for a full discussion of the dating question.)

St John is thought to have lived up to AD 94 or 96 and his gospel may have been written as early as AD 50-70, but no later than AD 90-100. This means that P52 was written around half a century after John wrote his gospel and possibly within a decade! The fact that the text on the fragment can be reconstructed using our present text of the gospel is indication that at this early date John's gospel was in the form in which we have it today.

in the form To be a proper scholar, I suppose I should add, "at least as far as the 18th chapter of the gospel is concerned", but such scrupulousness always reminds me of the story of a mathematician and a computer scientist travelling by train through the Scottish Highlands. One of them sees a sheep in a field and exclaims in surprise, "Look at that! Scottish sheep are white." (Presumably he thought that Scottish sheep should be tartan or something.)

His companion shook his head gravely and said, reprovingly, "You can't be sure of that. All you can say for certain is that one sheep in Scotland is white."

Our friend thinks for a moment and then admits, "Actually, I can't even say that for sure. All I can say is that one side of one sheep in Scotland is white." Return