Archaeology and the Bible

Ezekiel-Daniel

Tel Aviv

We are all familiar with the modern city on the coastline of Palestine; what most are unaware of is that the name comes from the Biblical book of Ezekiel and probably refers to the sand dunes which once covered the area. The origin of the name is uncertain; in Hebrew it is linked to a word meaning "spring", while others suggest "growth" in general or "barley ears" in particular. In fact, the name appears to be a transliteration of an Akkadian term which means "mound of the flood", and there appear to be several localities with this name in Mesopotamia.

The "River Chebar" mentioned in Ezekiel is almost certainly the nar kabari or "Kabari Canal" mentioned in the archives of the Murashu family. It was a significant canal used for both irrigation and transport and ran from Nippur to Babylon. Some have identified it with the modern Shatt en-Nil, a former bed of the Euphrates which ran through the middle of Nippur. Kabari is linked to the Arabic kebir which means "big", so the Nar Kabari could be rendered as "Grand Canal".

It is often assumed that Ezekiel and his fellow captives had been settled in the area in order to keep the canal functioning, for such waterways needed constant maintenance to dredge them of silt and also to keep them clear of water-weed. However we know that Nippur tended to favour the Assyrians over the Chaldean rebels and Nebuchadnezzar had to conquer the region by force. It is possible that the Judean exiles were settled in the area to replace the native population which had been either decimated or deported. This latter explanation would explain the considerable freedom enjoyed by the prophet in travelling from place to place and also in spending well over a year lying outside his house. It is also suggested by the rise of the house of Murashu in Nippur, which was on the Nar Kabari.

There is little else in the historical sections of the book of Ezekiel to which archaeology has any relevance, other than that nothing in the book contradicts what we know of Mesopotamia from archaeological discoveries. For example, the bricks of Mesopotamia were square and thin and thus an ideal base on which the prophet could build his model of Jerusalem (chapter 4). Mesopotamian houses were made of mud-brick and could thus be dug through (chapter 8) without causing the house to collapse, as opposed to houses in Palestine which were made of stone and digging a hole in a wall would seriously imperil the rest of the building. The custom of exposing female babies (or, indeed, any unwanted baby), alluded to in chapter 16, was distressingly common.

Prophecy

Ezekiel makes a number of predictions about the fates of the nations around Israel. The longest of these predictions concern Phoenicia (chapters 26-28) and Egypt (chapters 29-32) and the predictions are so specific that it is not unreasonable to look in the historical and archaeological record to see whether they have been fulfilled.

Tyre, one of the chief ports of Phoenica, comes in for particular condemnation and the prophecy states that God will bring many nations against it, that it will be completely destroyed and its stones, timber and dust will be laid in the middle of the water. Furthermore the city will never be built again. Finally, God says that because Nebuchadnezzar worked for God against Tyre yet received no reward for his labour, he will be given the land of Egypt as "wages".

Nebuchadnezzar laid siege to Tyre for 13 years, from 585-572 BC, but although he appears to have captured the city on the mainland, the people escaped to an offshore island where they were able to maintain themselves with the aid of their fleet. The struggle ended with the Tyrians paying a nominal tribute. A tablet in the British Museum refers to an invasion of Egypt by Nebuchadnezzar in his 37th year, but no details of his success or otherwise are preserved.

In 332 Alexander the Great laid siege to Tyre and again the mainland city was fairly easily captured, but the citizens fled to their offshore island. During the seven months of the siege Alexander used the ruins of mainland Tyre to build a causeway out to the island, digging up the foundations of the city and clearing it down to bedrock for material. Excavations at Tyre have not uncovered any remains earlier than the Greek period.

There remains only the conundrum of how God could predict that Tyre would never be built again, yet there was a flourishing Greek city of that name and there is still a city named Tyre.

| |

| An old steel engraving of Ras al-Ain, the fountain which supplied Tyre with water. |

The answer lies in the geography of the place. Some four miles south of modern Tyre is the copious spring of Ras al-Ain and the mainland city was located to take advantage of the water supply. Modern archaeology dismisses this settlement as "mere suburbs", but that is to ignore the historical fact that the Phoenician town was destroyed to create Alexander's causeway. There is nothing left to be found, so it is hardly surprising that the archaeologists haven't found it!

The island, which by the time of Alexander was a heavily fortified and densely populated city in its own right, was probably little more than bare rock in the time of Ezekiel. Its value lay in the protection it afforded to ships anchored in the sea off the mainland city. Whatever buildings were on the island were probably warehouses and dockyard installations.

Ezekiel's prophecy concerned the mainland town, which was both destroyed as predicted and has never been rebuilt - though it is only fair to note that the recent growth of modern Tyre may eventually swallow up the site of the ancient city.

At the end of the predictions about Tyre is a brief reference to the equally famous city of Sidon whose fate is summed up in two verses that predict disaster and massacre but lack any specific claims about the city being thrown into the sea or never being rebuilt. Again, the history of Sidon confirms the prophecy, for Sidon has been subject to many masscres over the years, yet it has always been rebuilt on the same spot and it is only recently that archaeologists have been able to take advantage of the larger buildings now being erected to excavate more than a cramped backyard. The finds have been significant, indicating the riches of Sidon and confirming that the city has always been built and rebuilt on the same site.

With regard to Egypt God predicts that it will never again have a native ruler, it will be "the basest of kingdoms", the papyrus plants will "wither", and the land will be reduced to desolation for forty years to such an extent that "no foot of man shall pass through it" (29:10).

| |

| A small stand of papyrus at the Pharaonic Centre in Cairo. |

From the time of the Persians onwards Egypt has never had a native Egyptian ruler: Persian governors, Greek kings (the Ptolemies, of whom the last ruler, Cleopatra, is probably the most notorious and the best known), Roman and Byzantine governors, and Arab rulers who continue down to the present. The survivors of the native Egyptians, known as Copts, are sedulously kept out of government because of their Christian religion.

Although Egypt once supplied papyrus to the world, there is now very little papyrus in Egypt. At one time all that remained was a small patch in an artificial pond outside the Cairo Museum; now it has been reintroduced in other places such as the "Pharaohinic Village", where it appears to thrive, but the great beds of native papyrus appear to be a thing of the past. The reasons for this remarkable decline are not known but are probably related to over-exploitation as both food, fuel and writing material rather than to climate change as previously thought.

The reference to forty years of desolation is more problematic, for the Hebrew appears to say "from Migdol (tower) to Syene and to the borders of Cush (Ethiopia)". In fact opinion is divided on whether it might not be better translated "From Migdol Syene to the borders of Cush". "Migdol" or "tower" also means "fortress" and although there is a town called Migdol in northern Egypt, Syene or Aswan was certainly a fortress, the great border fortress guarding Egypt's southern frontier against the wild men of Cush, which in ancient times was not Ethiopia but the area we known as Sudan.

| |

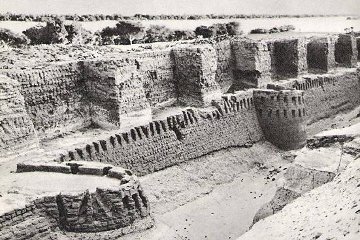

| An old photograph of the amazing fortifications of Buhen, just across the river from Abu Simbel. Although built of mud-brick, the architechture is reminiscent of the much later Crusader castles. |

For a long time Sudanese or Nubian archaeology lagged behind that of Egypt proper, but with the construction of the Aswan High Dam considerable work was done in the areas to be flooded, which revealed that the area between Egypt's southern border and the kingdom of Cush was rich in remains, both of the native culture and also of the Egyptian invaders. Great mud-brick fortresses such as Buhen and Semna were discovered - now, alas, lost forever to the waters of Lake Nasser - as well as temples, tombs and caravan towns.

What particularly interested me when I read about these discoveries was the fact that all this activity depended on the trading links between Egypt and Sudan and there was archaeological evidence that when these broke down, due to instability in either country, the area was more or less deserted. Although it is not yet possible to point to any particular dates and say that "this" was the start of the 40 years of desolation and "this" the end, nonetheless it is entirely likely that at a time when Egypt was being wracked by civil strife - as occurred during the Persian period - there might indeed be a generation when no traders with their strings of animals passed between Aswan and the border of Nubia.

Archaeological work in Sudan is still in its infancy, compared to Egypt, and we can expect that further discoveries will be made, so it is possible that in the future we will be able to identify this 40-year period of desolation.

Daniel

Daniel is frequently classed as a late book, written around 164 BC by an anonymous author masquerading as an ancient prophet in order to encourage his countrymen in their struggle against the Seleucids. In this respect it is interesting to compare Daniel with the apocryphal book of Tobit, which is thought to have been written about the same time. Tobit contains glaring contradictions of what is known about the history and culture of Assyria, whereas every detail in Daniel which can be checked is in harmony with the history and culture of Nebuchadnezzar's Babylon.

In Daniel chapter 3, the story of the Fiery Furnace, there are two Greek musical instruments listed among the band or orchestra whose playing was to be the signal for all to fall down and worship. This was held by critics to be evidence that Daniel was written after Alexander's conquest of the Middle East. In fact, inscriptions from Babylon show that Nebuchadnezzar had a guard of Greek mercenaries, making it entirely possible that Greek instruments were being used by Nebuchadnezzar's band.

The Bible records Nebuchadnezzar as boasting, "Is not this great Babylon which I have built?" whereas all other ancient Greek sources attribute Babylon to a Queen Semiramis. Today, of course, we know that Semiramis was the myth and the huge number of bricks from Babylon which bear Nebuchadnezzar's name attest to his comprehensive rebuilding of the city.

| |

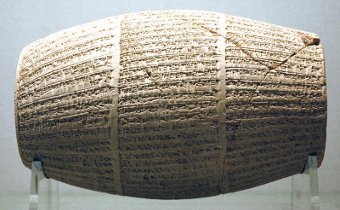

| The Nabonidus Cylinder confirms that Belshazzar was the son of Nabonidus. |

Perhaps the most dramatic demonstration of Biblical accuracy is the reference to Belshazzar as the last king of Babylon. Ancient Greek sources named the last king of Babylon as Nabonidus and this was confirmed when Koldewey dug up Cyrus' own account of his capture of Babylon, the Cyrus Cylinder. This was deemed to be one of the more egregious "mistakes" which proved a late date for the book of Daniel.

However in 1861 H. F. Talbot pubished a prayer by Nabonidus on behalf of his eldest son Bel-shar-usur that had been found in the Moon Temple at Ur. Unable to believe that the Bible might be right, Talbot argued strongly against identifying Bel-shar-usur with the Biblical Belshazzar, even though George Rawlinson had no doubts. In 1882 Theophilus Pinches translated the Nabonidus Chronicle, which revealed that Nabonidus went to Tema while his son, Bel-shar-usur, remained in Babylon. This seemed to settle the question of Belshazzar's existence, though he was not called king in either of these texts, nor in the others that were discovered in the following years.

In 1916 Pinches published another text in which Nabonidus and Belshazzar were jointly invoked in an oath, leading him to deduce that Belshzzar "must have held a regal position". Only in 1924, when the Verse Account of Nabonidus was translated, did we have the confirmation that Belshazzar was indeed co-regent with his father. A disgruntled "Higher Critic", Professor R. H. Pfeiffer of Harvar University, wrote:

We shall presumably never know how our author learned ... that Belshazzar, mentioned only in Babylonian records, in Daniel, and in Baruch 1:11, which is based on Daniel, was functioning as king when Cyrus took Babylon.

Introduction to the Old Testament New York, 1941, p. 758, 759

The mystery of how a a 2nd century BC Jew might learn something that none of his contemporaries remembered was easier for Professor Pfeiffer to swallow than the thought that Daniel might actually have been written by someone living in the 6th century BC who was able to predict the future.

Combining all our sources, we learn that Nabonidus appointed Belshazzar as co-regent when he fell ill in his second year while campaigning in the Lebanon. Upon his recovery he appears to have left Belshazzar as ruler in the city and province of Babylon, while he himself retreated to Tema in Arabia and ruled the rest of the kingdom. Thus the offer of "third ruler in the kingdom" made by Belshazzar as the reward for interpreting the mysterious writing on the wall is strictly accurate. Being the second ruler himself, he could offer no higher reward than "third ruler".

Assyrian reliefs depict lions being transported in cages to where they could be hunted, while a building at Ebla is identified as a lion den, making the story of Daniel in the Lions' Den entirely believable. Lions were kept to be hunted - rather as a grouse moor is guarded by keepers who jealously protect the birds until they can be slaughtered by "huntsmen". If condemned prisoners were thrown into the den, it saved on the meat bill!

Even the story of Nebuchadnezzar's madness finds support in a tablet from the British Museum which appears to come from the early Neo-Babylonian Empire period and describes a king who has become mad, who orders temples to be destroyed and nobles to be executed. The tablet is badly broken, so the name of the king is lost, as is any indication of what happened to him, but it would fit with the archaeological facts if the king was Nebuchadnezzar and the insane acts he commands were symptoms of the madness that caused him to driven out into the fields for seven years.

About the only detail not confirmed is the identity of Dairus, mentioned in chapter 6. Although various suggestions have been made as to this man's identity, none have won universal support and there are serious objections to all of them. In view of the accuracy of other parts of Daniel which had been doubted, however, it would be dangerous to conclude that Daniel is mistaken on this point.

In fact, there are good reasons for thinking that Daniel is correct. Babylon was regarded as a sacred city and was always accorded the honour of having its own ruler or governor. This was the case even under the Assyrians, who frequently appointed the monarch's eldest son as ruler of Babylon.

The Cyrus Cylinder and the Nabonidus Cylinder both make it plain that Cyrus came to Babyon in the guise of a deliverer from the wrongful rule of Nabonidus. No communist invader or revolutionary strongman ever did a more thorough hatchet-job on his predecessor than Cyrus did on Nabonidus: he was mad, he abandoned the worship of the gods, he kidnapped the gods from their rightful homes, he oppressed the land and its people - the list is pretty damning. Cyrus, on the other hand, posed as the ruler who restored the worship of the gods and allowed the sacred images and objects to be taken back to their original homes. He gave liberty to the people also and allowed them to return to their homes.

In this guise, therefore, Cyrus would hesitate to take direct rule over Babylon; rather, he would appoint a king in Babylon that the Babylonians could view as their own ruler. The Persians might be the occupiers, but they had restored freedom to Babylon! When Darius appoints 120 princes over "the whole kingdom", he was appointing governors over Babylonia, not over the whole Persian empire. Darius' failure to see through the machinations of these men and his folly in accepting divine honours from them may be what decided Cyrus to abandon the experiment and incorporate Babylon fully into his empire.

Apocryphal Daniel

Some versions of the book of Daniel contain sections which are not generally accepted as authentic: these are the prayer of the Hebrew children in the Fiery Furnace, and the stories of Bel and the Dragon, and Susannah and the Elders. The Prayer is an example of the speech-writing that was to be so prominent a part of popular Greek literature, an opportunity for the author to show-off his rhetorical skills. Josephus, for example, never recounts a battle or other significant event without inserting a page and a half of speech by the chief actor in the drama.

The stories of Bel and the Dragon and Susannah and the Elders, on the other hand, show a different emphasis to the rest of the book. In the Canonical Daniel, the problems faced by Daniel and his companions are solved by divine intervention: Daniel is given the same dream as the king, his three companions are miraculously delivered from the flames, Daniel alone can interpret the king's dream and read the mysterious writing on the wall, and God's angel shuts the mouths of the lions. In the apocryphal stories it is Daniel himself who, by his cleverness, provides the solution. The dragon is destroyed, not by divine power but by a bolus of bitumen and sulphur Daniel feeds it; the priests are unmasked by Daniel sifting ashes on the floor that displays their footprints and betrays the hidden door; the lying elders are exposed by Daniel questioning them separately and noticing the contradictions in their witness.

In addition there are details of the stories which do not accord with what we know of Babylonia and the language and style points to a later origin for these portions than for the rest of the book.

"mound of the flood" The Akkadian word abubu is only used of the great deluge associated with Utnapishtim and is related to the Hebrew mabbul, which refers to Noah's Flood. An ordinary flood, such as occurred annually in Mesopotamia and Egypt, was never abubu. Not only does this fact have implications for the interpretation of the Flood story in Genesis, but it means that Tel Aviv, the "mound of the flood" is not a muddy sandbank washed up by the last spring floods, but a mound that has been in existence since the Deluge.

Another possibility notes that the Assyrians boasted that their armies swept the land "like abubu", so in view of the fact that the word tel means "ruin" as well as "mound", it could be the "Ruin destroyed as by the Flood". I leave the determination of such arguments to the experts.

Even more interesting to me is the suggestion that abubu comes from the verb ebebu which means "to purify" or "to cleanse". That links in both the Babylonian and the Biblical stories which state that the Flood was sent to purify the earth from the wickedness of men. Abubu is depicted in reliefs and seals as a lion-like creature with the wings of an eagle or vulture. Return

Belshazzar existed The Cylinder states (in part):

ReturnAs for me, Nabonidus, king of Babylon, save me from sinning against your great godhead and grant me as a present a life long of days, and as for Belshazzar, the eldest son, my offspring, instill reverence for your great godhead in his heart and may he not commit any cultic mistake, may he be sated with a life of plenitude.

the only detail Amidst this plethora of authentic confirmation for the book of Daniel should be mentioned a couple of highly dubious "finds". Professor Koldewey, as dour and serious a scholar as Germany ever produced, grew heartily sick of visitors to his excavations who demanded some sensational confirmation of the Bible story and in his ponderous Teutonic way occasionally took his revenge by means of a practical joke.

The story goes that one party of earnest American clergymen arrived and expected to be shown round by the professor in person, and Koldewey grudgingly obliged. While walking over the ruins one of these gentlemen picked up a fragment of brick on which was the usual dedicatory inscription, and demanded that Koldewey read it to him. Koldewey took it and glanced at it, then affected an expression of immense surprise and in a hushed voice said, "Do you know what this is? It says, 'Mene, Tekel, uPharsin'!"

The clergymen were delighted and begged Koldewey for the piece so that it could be exhibited in America with all due honour. Koldewey, perceiving that he had gone a little too far and that were such an exhibition to take place he would be made a laughing-stock by the first expert in cuneiform who happened along, shook his head. He solemnly explained that much as he wished to oblige his new friends, such an important find would have to go to the sponsors of his excavation.

As soon as the disappointed clergymen were out of sight, of course, Koldewey threw the worthless bit of brick onto the rubbish heap. Nonetheless, one still occasionally comes across the claim that the mysterious inscription has been found!

When we first visited Babylon in 1958 we were shown round by an Arab called Amram, a former workman with Koldewey who had become a guide to Babylon. His English, mangled by an Arab accent overlaid with a German accent, was difficult to follow, but his information was, on the whole, no more untrustworthy than any other guide's. However he appeared to have inherited Koldewey's sense of humour and pointed out to us a hole in the Ishtar gateway from which, he claimed, an inscription confirming the story of Daniel in the lions' den had been removed. He further identified the courtyard of the gate as the den in question.

Fortunately we realised that a gateway was an unlikely place to keep ferocious lions and were duly sceptical of the claim - a scepticism which appears to be thoroughly justified! Return

divine honours The Persians were never so foolish as to regard their kings as divine, but the Babylonians (among others) appear to have done so. The Medes were the priestly class in Persia, so it may have been easier for Darius to accept the prayers of the populace in view of his semi-religious status. In addition, he may have felt flattered that the stiff-necked Babylonians were coming to accept him as ruler and viewed the 30 days of praying to him as evidence that he was succeeding in winning them over to Persian rule. In the event he was to be sadly disillusioned! Return