Aesop On-line

As readers of this website will be aware, I hold very strong views on ownership and copyright of museum and library collections. I maintain that the objects in the museum do not belong to the museum, nor to the country where they are held, nor even to the country of origin (perhaps especially not to the country of origin!) I believe that these objects belong to the world and the museums and libraries are merely custodians of the objects which are to be preserved for the world - for you and me.

While no one objects to a reasonable charge being made for access or photography - museums have expenses, just as much as any one else - unreasonable profiteering or restricting access is not acceptable. Neither, in my opinion, is the sort of toffee-nosed attitude displayed by the Greeks, who get all upset if you take a photograph of your wife or girl-friend posing in front of their precious monuments.

I disapprove of a frivilous attitude towards important things, but there are so-called scientific studies of which I also disapprove. It is not clear to me that my opinions about what is a legitimate use of antiquities should be determinative. I remember meeting a young lady from a certain part of the world; she was friendly and had a bubbly personality, but oil painting she was not. She had travelled extensively and in an incautious moment I expressed an interest in seeing some of her photographs - which, like all true amateurs, she was only too ready to show me.

The results were as I might have expected. Every photograph consisted of this hideous grinning gargoyle taking up most of the foreground, while behind her left shoulder or sticking unexpectedly out of her right ear was a single pillar of the colonnade in front of St Peter's in Rome, one hip of Venus de Milo, the flag on top of the Eiffel Tower or the blue sky over the Parthenon. She beamed proudly as she displayed these evidences of her visits to famous places - and who am I to say that this was not a legitimate use of those famous antiquities?

Naturally my pictures are better. You can actually see the object in question and you never, ever, see me in the picture - but that is what I like, that suits my purpose in taking such pictures. Her pictures were what she liked and suited her purpose for them and who is to say that the one is better or more valid than the other?

In other words, so long as the object in question is not being harmed by the activity and so long as the custodian of the object is adequately (but not exhorbitantly) rewarded for preserving the object, then anything goes and the more the merrier.

To take a case in point: at one time you had to see the head of the Cairo Museum and obtain written permission to take photographs. Then, later, photography permits (rather expensive) could be obtained from the ticket kiosk. I was happy with both arrangements and possibly preferred the first, even though it was a nuisance. Now Zahi Hawass has banned all photography in any museum or tomb in Egypt - and that, I believe, is wrong. He does not own the death mask of Tutankhamun, Egypt does not own it; I own it - and so do you.

As a protest against Zahi's improper restrictions, as soon as I have exhausted my pictures of Turkey, I intend to post 1280x840 pixel pictures of objects in the Cairo Museum as "Picture of the Week". Copyright busting? Yes, and proud of it.

A much more enlightened attitude is shown by the British Museum, where photography is allowed freely. Tripods are forbidden, but only because the place is often so crowded that there is a real danger that visitors might trip over the extended legs; you could, however, use a monopod if you so wished - or even use your tripod as a monopod, just so long as you did not open the legs. Flash was permitted, except in the manuscript rooms, but I have a feeling that there are now restrictions on flash, probably owing to the abuse of it by the ignorant.

I applaud such a liberal policy. There is the possibility that the intense light of a flashgun might damage the fragile pigments in the Lindisfarne Gospels or the Book of the Dead (I am dubious, myself, but I admit the possibility and do not find it unreasonable that the museums should be cautious). When, however, you have an unpainted lump of granite that has stood out in the Egyptian desert for 4,000 years, the possibility that it wil be damaged, even if a million tourists take flash pictures of it every day, is laughable.

The same enlightened attitude extends to the British Library, which is busy digitising its fabulous collections and making them freely available to anyone and everyone. Among the books already available on-line are the fabulous Lindisfarne Gospels with their intricate knot-work and mythical beasts, the Codex Sinaiticus, whose reading cost Tischendorf his eyesight, the Library's collection of Leonardo da Vinci sketches, and extending all the way down to 19th century newspapers and other mundane documents.

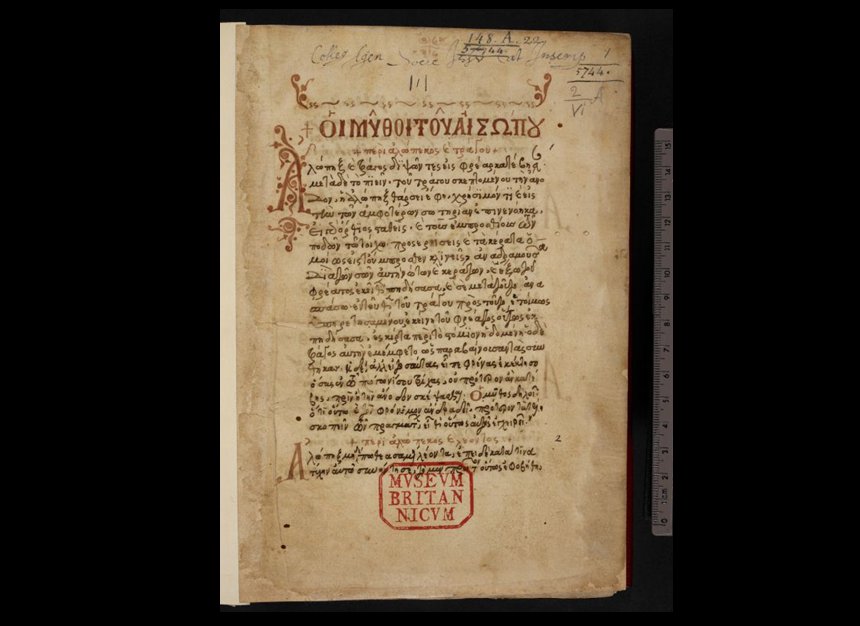

The latest is a one thousand volume collection of Greek codices, that includes a collection of Aesop's fables discovered on Mt Athos in 1844. Many of these books are so fragile that access to them has been severely restricted, even for bona fide scholars. They have to be handled so carefully that the Library estimates that it costs them £1.00 to open and photogrpah each page and the Library is grateful - as we should be too - to the Stavros Niarchos Foundation for sponsoring this project.

So far a quarter of the thousand volumes have been processed and are available on-line at the Library website and it is planned that another 250 volumes will be available by 2012.

| |

| This is a picture of the first page of Aesop's Fables, captured using the technique described below. Click on the picture to see it full size |

I cannot applaud the British Library too much for this generous and enlightened work. There will be serious scholars who will now be able to study these documents without the expense of travelling to London and living in an expensive hotel while conductng their researches. There will be casual browsers like you and me who simply want to flip over the pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels and raise an appreciative eyebrow over a picture here or there. There will be children who want a picture to illustrate a school project. All can now access this wonderful collection and should mutter a prayer of blessing and thanks on the British Library and its curators as they do so.

I look forward to the day when the whole of mankind's heritage is available on-line. It won't cut down on visitor numbers to museums, art galleries and librares, for no matter how good virtual reality gets, it will never be as good as seeing the actual object. Not even a data glove that allows you to "handle" the virtual object, can take the place of standing on a chilly museum landing and gazing up at the marble perfection of the Venus de Milo or pushing your way through a mob of gesticulating, garlic-ridden Frenchmen for a glimpse of that famous smile of the Mona Lisa.

As for other things, no matter how perfect the photograph, you simply cannot grasp the awe of the Great Pyramid until you stand on the desert in front of it and see it towering over you. No matter how brilliant the video, nothing can take the place of standing by Niagra Falls and feeling the spray misting your hair and being deafened by the thunder of the waters.

Virtual reality will never take the place of real reality, but free access to the collections of museums and libraries will allow us all to experience and appreciate the heritage which belongs to all of us and to use it in ways that are meaningful for us personally - and no toffee-nosed curator, no money-grubbing librarian, no perversely patriotic attendant will be able to interfere.

===========

abuse of it There is a reason why simple cameras are referred to as "idiot boxes"; it is not because they are so simple that they could be used by an idiot - though that may be true. It is because the people who use them are, generally speaking, idiots and nowhere is this idiocy more evident than in the use of flash.

Your average compact camera has a flash whose effective range is 2-18 feet. Closer than 2 feet and there is too much light, further away than 18 feet and there is too little light. (Look up the "inverse square law" if you want further details.) Yet you see idiots standing 1,000 feet away from the Great Pyramid or the Great Wall of China and sedulously switching on their flash!

A flash works by flooding the object with light - white light, of course. So why do idiots use flash in order to capture the faint red, purble, blue and yellow light of a son et lumiere or the delicate shades of a floodlit building?

Finally, glass reflects light - if you don't believe me, go shine a torch into a mirror. Stand in front of a museum case and fire off the flash on your camera and quite apart from any damage that may or may not be done to the object inside the case by your flashlight, the entire centre of your picture will be a blinding blob of white.

In all these situations, turn off your flash, prop your camera on something steady like a wall or the back of a chair - or if nothing like that is available, relax, take and gentle breath and hold it - and then gently squeeze the button on your camera and hold it down for at least one or two seconds before releasing it and lowering the camera. In these days of digital cameras you can afford to ruin two or three pictures in order to get the ideal shot and if none of them work, then you can try flash - but remember to get within 18 feet of your subject! Return

illustrate a school project In actual fact, you may find that less easy than you might have hoped for, as the website uses clever technology that disables the Right-click-copy function. I really don't know why people bother. Get the bit you want up on screen and then press the "Print Screen" button on your computer (make sure your printer is turned off or disconnected, otherwise the computer will simply print the picture out on paper). This saves the entire screen to the clipboard, from where you can paste it into any document you want.

If you don't want the entire screen, use a program such as Photoshop or the Gimp (which is open-source and free of charge) to select the bit you want and crop the rest of the screenshot away.

Of course, this is a tedious way of doing things and the resolution is likely to be limited. I wish the Library would include a button on their page which you could click and then order - and pay for - a high resolution copy of the page for scholars or a lower resolution and cheaper version for the aforesaid school child. In these days of PayPal and automated on-line transactions, there is no reason why the Library should not do this and make a small profit which can go towards the next round of digitising. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2010