On-yer-bike Artists

Tel ed-Dab'a, better known to many as Avaris, was the Hyksos capital during the Second Intermediate Period. Its capture and destruction by Kamose marked the end of Hyksos domination in Egypt and the city lay in ruins until Rameses II decided to make it the capital of his kingdom, renaming it Pi-Rameses.

|

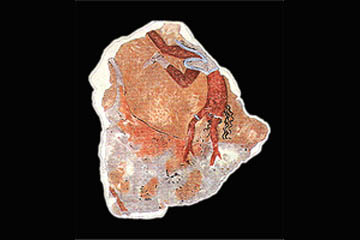

| A fragment of painted plaster from Avaris, claimed to depict the famous bull-leaping scene from Knossoss. |

The site is, of course, littered with broken stone work and sherds of pottery and excavations turned up much more of the same. However as archaeologists led by Manfred Bietak worked on the site they discovered a couple of fragments of painted plaster that continue to pose a mystery. Two buildings, identified variously as palaces or temples, were decorated with painted plaster, but the paintings are distinctly Minoan in style and one fragment has even been claimed to be part of a "bull jumping" scene similar to the large fresco discovered in the ruins of Knossoss.

In 2007 Bietak published a book dealing with the problem posed by these frescoes and claiming that they come, not from the Hyksos period but from the time of Tutmoses III. This, in itself, is surprising, as there is little other evidence that Avaris was occupied until the time of Rameses I, who is thought to have established a summer palace on the site. Bietak's suggestion is that the building was constructed to welcome either a high-level Minoan delegation into Egypt, or on the occasion of a marriage with a Minoan princess. In either case the paintings didn't last long, as the plaster appears to have fallen off the walls after only a few years, indicating both haste and carelessness in the construction and disregard afterwards - possibly even removal of a roof and exposure to the elements.

However Professor Maria Shaw of Toronto University has come up with a new idea. She is an expert on Crete and its civilisation, but perhaps not so knowledgeable about Egypt. She also appears to have strange ideas about religion. According to her, Minoan paintings were so sacred that it was unthinkable that they should be allowed outside Crete and preferably outside the great palace at Knossos. (It does appear to be true that such paintings have not been found at any other Minoan palace in Crete.) She claims that half-rosettes are an infallible sign of royalty and professes to be amazed that they were used at Avaris.

Her conclusion is that as the power of Knossoss waned, artists employed there were sacked and consequently travelled to Egypt looking for work. Because Knossoss was weak, they were no longer afraid to use its "sacred motifs" in other places, and so dared to paint on the walls of Avaris.

My conclusion mirrors that of the Roman governor Festus to St Paul: "Much learning hath made thee mad!" Allow me to point out that the Sistine Chapel took umpteen years of Michelangelo's life - and after that he was unemployed! No matter how great an artist's skills, once the job is over he has to go and look for work elsewhere. In exactly the same way, once the frescoes at Knossoss had been painted, the artists who painted them were unemployed and had to go looking elsewhere for employment - and while it is true that some of them may have travelled to Egypt, that had nothing whatsoever to do with the rise or fall of Knossoss.

On such a simple fact does her high-falutin' theory fall to the ground. After all, as Ms Shaw herself points out, none of the other palaces in Crete were decorated in the same way, so a wealthy, art-loving culture across the sea was the obvious destination for the unemployed artists of Knossos.

Mind you, while one or two Egyptians may have been interested in this new and exotic style of art, Egyptian artistic tastes were notoriously conservative, and a few sniffs from those higher up the social ladder and some scathing comments from a blogging scribe may have been all that was required for the new frescoes to have been abandoned and a more conventional scheme of decoration employed.

Tutmoses III Others have suggested an earlier date for the frescoes, linking them with the end of the Hyksos empire and the rise of the Seventeenth Dynasty. They point out that Queen Ahhotep II, mother of Ahmose who led the revolt against the Hyksos, bore the title of "Mistress of the Shores of Hau-nebut", a term which applies to the Aegean islands. Although Ahhotep was certainly Egyptian, not Minoan, she may have had some special link with or responsibility for Minoan affairs, including trade. It is also pointed out that many of the motifs from Knossoss in fact occur in the throne room of a queen, so what more suitable than that they be employed to decorate the residence or even throne room of an Egyptian queen? Return

such a simple fact Even more damning is the fact that the style and context of the paintings at Avaris point to the Late Minoan I period, whereas the bull-leaping frescoes at Knossoss belong to the Late Minoan IIIA period. In other words, if we are going to talk about unemployment, it would be more accurate to speak of unemployed Egyptian artists popping over to Crete and doing up Knossoss a century or so later! Return

© Kendall K. Down 2010