What did Romans wear under their kilts?

Scotsmen, as we all know, wear a kilt. True Scotsmen, as we all know, wear nothing underneath the kilt. Given the voracious nature of Scottish midges - tiny mosquito like pests whose bite is like the pin-pricking of minitaure red-hot pokers and which swarm in millions around anyone unfortunate enough to be in Scotland between May and September - the thought of any unprotected flesh is painful. The thought of a swarm of midges congregating in the warm darkness underneath a kilt positively brings tears to the eyes.

The ancient Romans must have shared my opinion on the wisdom - or rather, the unwisdom - of wearing kilts without undergarments. Not that the Romans wore kilts exactly, but they certainly didn't wear trousers. Trousers were the garments of effete civilisations such as the Persians or the Sarmatians; real men - like, for instance, the Romans - wore togas in their leisure moments and short, kilt-like garments when off soldiering. Just consult any picture of a Roman legionary to see what I mean.

Of course, the Roman artists and sculptors whose works have come down to us did not give us any indication of what was worn underneath those skirts, but a chance discovery at Vindolanda reveals all.

In 1970 Robin Birley, Director of Excavations of the Vindolanda Trust, was excavating around the commandant's house in the centre of the pre-Hadrianic fort when he found the commandant's rubbish heap. To the archaeologist, few things are more exciting than a good rubbish heap, for it will be a treasure trove of broken pottery (dating), gnawed bones (diet), vegetable scraps (diet again), broken tools and furniture (life and culture) and, indeed, anything and everything that was thrown out as no longer useful.

The rubbish heaps that we have excavated in the Middle East have been dry and dusty and it is best not to allow your mind to dwell on the origin of the rich brown soil that you are sifting through your fingers. To Dr Birley's delight, however, the Vindolanda rubbish heap was water-logged - which to my mind would have made the task of excavating it doubly distasteful.

In the Middle East that would have been a disaster, for it is dryness that has preserved the ancient wood and fabric, papyrus and parchment that is the pride of any excavation. However in cooler, wetter, northern climes you simply are not going to find anything dry. The next best thing is to have it thoroughly wet, as a really soggy bit of bog is going to favour anaerobic conditions which are almost as effective as desert dryness at preserving organic matter.

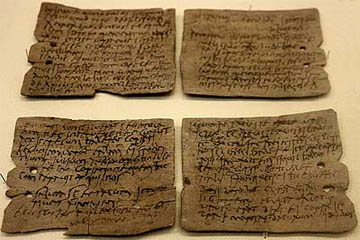

Among the rubbish that Birley's team recovered were dozens of thin pieces of wood, most of them between 1mm and 3mm thick and about the size of a modern postcard. As soon as Dr Birley saw them he felt a shiver run up his spine, because these were literally Roman postcards. Cheaper than papyrus or parchment, they were used by everyone from emperors to slaves for sending written messages or writing down things that they didn't want to forget. The Roman historian Herodian tells of how the Emperor Commodus used just such a slip of wood to jot down the names of those he suspected of disloyalty. The wood was then passed on to the chief of police and those on the list eliminated. (Unfortunately for Commodus, his slip of wood got into the wrong hands and the people on the list banded together to assassinate the emperor simply to save their own lives.)

The technique was to write your message on one side of the "postcard" and then fold it in half. Obviously wood, no matter how thinly sliced, does not bend like paper, so it would break along the fold, but not actually break in half. On the outside of the folded bit of wood you wrote the address to which you wanted your message to go, then you sealed the wood shut with a dab of wax and handed it over to the postman for delivery (or a friend or a merchant or anyone you could trust).

|

| Four of the Vindolanda Tablets which give us a vivid picture of life on Hadrian's Wall. The holes were used to join the tablets to make a longer document. |

The Vindolanda Tablets are made of birch, alder or even oak and nearly 400 of them have been found, the majority from the commandant's rubbish dump but others from various locations throughout the camp. Clearly Vindolanda was a hive of literary activity. Some of it was official, such as the list of military personnel from the cohort I Tungrorum which reveals that while the total strength was 752 (including 6 centurions) there were detachments all over the place: 6 men in Gaul (probably on leave, because the cohort originally came from there) and a centurion in Londinium (probably carrying despatches to the governor) as well as men manning the auxiliary fort at Corbridge and others in other forts along the wall.

A poignant note from Masculus to Cerialis (whom he respectfuly addresses as "my king") voices the soldiers' most frequent complaint: "My fellow soldiers have no beer. Please order some to be sent." Another is a list of wheat distributed - or sold - to various people, including a ration sent to the writer's father "who is in charge of the oxen" - which brings up the most fascinating part of this find, for we rarely have both sides of the exchange of letters, so we have to use our imaginations to fill in the rest. What was this man's father doing with the oxen? Why had the father gone with the oxen instead of sending his son?

Others, however, were personal notes. The most famous of these is the note from Claudia Severa to a close friend. "Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On the third day before the Ides of September. Sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival."

However the note which prompted my introduction is from an anonymous soldier to an equally anonymous friend, informing him that "I have sent you ... pairs of socks from Sattua, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants (subligaria)".

Josephus tells the tale of a Roman soldier on guard duty in the Temple in Jerusalem who insulted the crowds of worshippers on one occasion by bending over and "mooning" at them, which indicates that underpants were not normally worn by the legionaries. Presumably the chill winds that whistle around Hadrian's Wall and the crags and hills of Northumberland were the incentive for soldiers posted there to desire something under their kilts.

If you want more information about the Vindolanda Tablets you can find them online but if you want to see them "in the flesh", so to speak, it is difficult to know what to recommend. Ever since their discovery they have been held in the British Museum in London, where a selection of them are on display. However the Vindolanda Trust has recently received a grant of four million pounds from the National Lottery, with which they intend to build a special gallery at Vindolanda where the tablets can be kept and displayed.

According to the press release, they will simply be on temporary, albeit long-term, loan, but four million pounds is a lot of money and I can't see the tablets being shuttled between London and Vindolanda on a regular basis, nor can I see the special gallery being left empty. It seems likely, therefore, that the collection will be more or less permanently split, with some being retained in London and others returned to Vindolanda.

As Linda Tuttiett, chief executive of Hadrian's Wall Heritage Ltd, announced, "The trust will finally be able to display the Vindolanda Tablets, this country's most significant historical find, and share their importance with a much wider audience."

Anything which promotes the study of archaeology and history is, of course, to be applauded, but if Ms Tuttiett thinks that a minor museum in northern Britain will command a wider audience - let alone a "much wider audience" - than the prestigous British Museum, she is suffering from delusions of grandeur.

© Kendall K. Down 2010