Seventeen New Pyramids!

Back in the days when we all used stone axes and rubbed sticks together to light fires, photographers were dependent on something called film. White-haired ancients like me will need no further explanation, but for the benefit of younger readers, let me explain.

Film was a strip of plastic coated on one side with a jelly "flavoured" with powdered silver - yes, actual silver. Kodak alone is reputed to have got through 35 tons of the stuff every day producing film to keep the world clicking. If you own any silverware, you will have discovered that it eventually discolours and turns black, which is why you need to keep polishing it (or coating it in a clear varnish to keep the air away from it). Powder it small enough and that discolouration can occur very rapidly indeed, which is why it was used in film.

| |

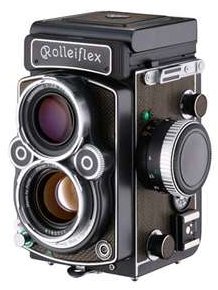

| The Rolleiflex twin lens reflex camera was state-of-the-art and very high quality. |

On our first trip to the Middle East in 1958 my father carried two cameras. One was a standard Rollieflex twin lens reflex that used 120 roll film and took black and white pictures 6cm x 6cm, twelve per film. The other was an Exacta single lens reflex which, in a highly daring and experimental move, was fed with 35mm colour film!

A word about both cameras and film: a twin lens reflex had two lenses mounted one above the other. The lower lens directed the light onto the film while the upper lens sent the light onto a mirror that reflected it up onto a viewing screen. When you were taking a picture of far distant mountains, the two views were pretty well identical, but when you got close to Aunty Mabel or Cousin George, the two views were different. Cameras of a poshness we could never afford actually tipped the upper lens downward slightly as you focussed closer; cheaper cameras simply had a line on the viewfinder and you had to remember to keep people's heades below the line when you got down to 6' away from them. If you have some old photographs of the family at the beach and the heads are missing, the chances are that your relative was a keen photographer with a twin lens reflex who got all flustered and excited and forgot to keep the line above their heads!

Black and white film was, as I have described, simply silver powder in jelly. Colour film was a different beast altogether, a fiendishly complicated mix of three layers of jelly separated by wafer-thin filters. The upper layer was somehow treated so that it was only sensitive to red light - I think red was the top layer. The light then passed through a filter that removed the red and allowed blue and yellow to pass. The next layer of jelly was sensitive to blue light and the third filter ensured that only yellow light hit the third and final layer.

The tricky bit was that not only did the lower layers receive less light, but when you came to develop the film the top layer was soaked immediately in the chemicals, but the lower layers took longer to become saturated and there was less agitation of the chemicals that reached them. In consequence the lower layers of jelly had to be made more sensitive, which meant grinding the powder slightly less finely to produce bigger grains of silver.

My Nikon slide scanner has a clever setting which can read the size of these grains and work out which layer they probably came from. If the slide you are scanning is over-exposed and washed out, the scanner software can use the grain size to recreate the probable colour and the results are remarkably good!

Getting back to the black and white, however: in those days every photographer carried a set of filters around with him. A blue filter, which removed the red light, was supposed to be advantageous when photographing your wife or girlfriend as it obscured skin blemishes. (A soft filter, which made the picture just ever so slightly blurry, was also used for the same purpose.) If you were into outdoor photography, however, you carried a yellow "haze filter" which removed the blue light whose short wavelengths were scattered by water in the atmosphere and allowed more of the longer wavelength red light to get through.

The effect, particularly as demonstrated in the advertisements in photographic magazines, could be dramatic. Distant mountains that barely existed in the "before" picture sprang into sharp focus, revealing crags and glaciers, swathes of forest and snow-capped glory, in the "after" picture. We never achieved such amazing results for the simple reason that we misunderstood the real purpose of the "haze filter" - possibly everyone suffered from the same misunderstanding.

It wasn't the removal of the blue that made such a difference; it was allowing more infra-red in that revealed the distant scene - and that depended on whether your film was sensitive to infra-red! In fact, if you wanted the ultimate in long-distance photography, you used infra-red film and a filter that was almost black!

| |

| A typical infra-red photograph with detail visible right to the horizon. |

Using infra-red film was not something to be undertaken lightly. You had to use a metal camera, because infra-red could go through black plastic as if it wasn't there! You had to have a metal shutter, because the rubberised cloth shutters of most single lens reflex cameras were virtually transparent to infra-red. And you had to handle the film in complete darkness - the dim red lights of so-called "dark rooms" were like blazing searchlights to infra-red film!

Mind you, even in the digital age infra-red has been somewhat of an unknown quantity. When Sony produced their first "night vision" video cameras, which relied on infra-red to see in the dark, male users quickly discovered that if you turned the night vision setting on in daylight you automatically removed the clothes of anyone passing in front of the lens! The results were not quite up to the standard of a Playboy photoshoot - bodies tended to be greenish and titillating fine detail was noticeable by its absence - but feminine outrage meant that Sony hastily introduced a modification which stopped the night vision feature being turned on in daylight!

However although infra-red photography had its place in the palette of any self-respecting professional, the digital age has made infra-red photography vastly more useful. Heat-seeking missiles rely on infra-red, as do the rather less destructive cameras used in searching for people buried by earthquakes or avalanches. Some of these infra-red detectors are so sensitive that a police helicopter can see the residual warmth left by a suspect's footsteps as he walks across a lawn!

Scientists have found that infra-red is useful from space; satellites equipped with infra-red cameras can tell the difference between a warm, healthy forest and one that is being ravaged by disease and whose leaves are slightly cooler as a result. Different crops produce different infra-red signatures and although to the naked eye a green corn field is identical to a green wheat field, infra-red can tell the difference.

In order to enhance the usefulness of these cameras, scientists have been using different parts of the infra-red spectrum and it is the "long infra-red" that is the reason for this subject cropping up in a website devoted to archaeology. Just as the early aerial photographers noticed spots and lines in their pictures which turned out to be crop markings revealing the presence of structures beneath the ground, so photographs taken using long infra-red have disclosed strange patterns that are now being recognised as buried buildings.

| |

| Dr Sarah Parcak shows off her excavation equipment - a computer and satellite imagery |

Dr Sarah Parcak, from the Egyptology department of the University of Alabama, has been looking at infra-red photographs taken by NASA satellites. I am not exactly sure why she started to do this - whether it was a chance remark by someone commenting on the strange patterns that were turning up or whether she was looking for something else entirely or trying to see through vegetation and crop cover, but she quickly realised that the patterns at which she was looking weren't just random markings but were, in fact, the outlines of houses, streets and other structures.

The reason is very simple: most buildings in ancient Egypt were made of mud brick which, naturally, is denser and more compacted than the friable soil that surrounds and covers it. Denseness equals heat retention and radiation, whereas the loosely-packed soil absorbs less heat and acts as insulation, giving it up less easily. The result is that like the criminal's footprints, the mud brick walls positively glow when viewed by infra-red. In fact, they can be seen even when they are buried several feet below the surface of the ground!

Her initial interest was in the city of Tanis in Egypt's delta region, where ancient remains are obscured by crops and several thousand years of silt. There she was able to more or less map the ancient city, for the infra-red pictures revealed the pattern of streets and houses and the size of the area enclosed by the building's walls gave a clue as to the nature and type of the building below. A large building constructed around a courtyard was probably a wealthy man's villa while a row of rooms each with a doorway into the street pointed to the tenements of the poor.

However Dr Parcak then turned her attention to Saqqara, where there is neither silt nor vegetation, and to her delight was able to detect structures beneath the burning desert sands. Not only did she observe shapes and patterns that could be long-buried tombs, but she also noted seventeen squares that were similar in size and orientation to pyramids.

Although Saqqara is most famous for the Step Pyramid of Pharaoh Djoser, there are many other pyramids in the vicinity, most of them in various stages of ruination, having been constructed out of rubble over which was laid a single layer of white limestone. When that was removed, the rubble quickly slumped to become a shapeless mound on the sand. The pyramids of Unas, Userkaf and several Tetis fall into this class. Egyptologists have identified 118 pyramids so far - a score more than were known fifteen years ago - so the addition of another 17 is a not insignificant find.

| |

| A structure believed to be the pyramid of Teti I's mother has been uncovered at Saqqara. Archaeologists hope to be able to enter it soon. |

Of course, these structures are merely similar in size, shape and orientation to pyramids. They may not be pyramids after all - the attitude adopted by the arrogant and unpleasant Zahi Hawass, the former head of Egypt's Antiquities Department. Dr Parcak's initial attempts to get on-the-ground confirmation of her discoveries were rejected and it wasn't until the BBC got involved and offered money for filming rights that Hawass changed his mind. Money and the chance to stand in front of a camera were always the way to his heart.

To Dr Parcak's delight, trial excavations at two of "her" pyramids revealed that the structures were indeed pyramids, one of which has been tentatively identified as belonging to the queen mother of Pharaoh Teti I, the founder of the Sixth Dynasty. Although its presence was unsuspected until Dr Parcak came along, the remains stand 16' high and were probably three times that height originally.

Hawass, naturally, hogged the cameras, claiming that it was all down to him and he had felt sure all along that there was a pyramid on the site. Fortunately the change of government in Egypt has led to Zahi's resignation, which can only make the world of Egyptology a better place.

Dr Parcak has also visited Tanis, where excavators following her lead have uncovered a 3,000 year old house whose excavated outline exactly matches the outline she had seen in her satellite imagery. A somewhat jubilant Sarah Parcak exclaimed, "Indiana Jones is old school. We've moved on from Indy. Sorry, Harrison Ford." She need not be too apologetic: whip-cracking, adventure-loving archaeology - if it ever existed - died out around 1890. Archaeology these days is all about using the latest tools and technology to investigate the past - and Dr Sarah Parcak has just added to our armoury.

daring and experimental My uncle-by-marriage, Asa Thoresen, was a respected ornithologist who made a pioneering study of puffins. His work received the ultimate accolade when he was invited by the National Geographic magazine to submit an article on these exotic birds, but the invitation was quickly withdrawn when the editor discovered that my uncle had shot all his pictures on 35mm colour film. That simply wasn't good enough for the exacting pictorial standards of the Geographic and poor Uncle Asa missed out on his moment of fame. Return

a modification The internet wasn't around in those days, but there was a flourishing underground of handwritten notes and duplicated pages which set out the steps required to undo or defeat the modification. As the process invalidated your guarantee and the results - as indicated above - were not as pornographic as early reports had indicated, the public soon lost its appetite for sabotaging good cameras. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2011