The Castles of Petra

| al-Wu'ayra Castle | 30 19 59.10N 35 27 57.60E | The coordinates should put you right in the middle of the castle. Immediately west is a circular tower. In the south-east corner of the enclosure the sides of the ravine on the east come close together and that is where the bridge stands (or stood). You'll have to take my word that the castle is much better preserved than this vertical view appears to indicate. |

| el-Habis | 30 19 48.19N 35 26 20.00E | The coordinates are merely of the summit of el-Habis. The area where walls remain is in shadow - as is the Hermitage at the foot of the climb. |

The question of the Crusader castle in Petra is one that has puzzled and confused a number of writers, and the confusion has been compounded by the fact that there are two castles in Petra, both apparently belonging to the Crusaders. Yet the records of the Crusades make scant mention of the castle at Li Vaux Moise - Wadi Musa - and tell us virtually nothing about its history.

On our first visit to Petra, when we were obliged to use the good offices of the Jordanian Tourist Police (a fine body of men) to negotiate a safe passage into Petra and to sleep in a tomb because there was nowhere else to sleep, it was received wisdom that the inhabitants of Petra never built, only carved. On that basis the temple in the middle of Petra was declared to be Roman - we now know that it is thoroughly Nabatean and was dedicated to Dusara - and the mass of stonework up on the High Place was identified categorically as the Crusader castle.

Knowing nothing better, we accepted the verdict. It was only on a later visit that we realised just how unlikely a castle this was, for though the wall that confronted us from the obelisks was massive enough to grace a mediaeval fortress, there were no towers or battlements and, more to the point, no walls anywhere else around the summit, so any putative attacker could have simply walked round the side and strolled in.

However, if the wall up on the High Place was not the Crusader castle, where was it? My father, whose interest begins around 1800 BC and ends in AD 70 or thereabouts, wasn't troubled, but I, with a broader range of interests, continued to niggle away at the problem every time we visited Petra.

Oddly, the breakthrough came miles away from Petra. On our early tours we followed the Desert Highway, a narrow ribbon of tarmac laid, apparently, on virgin sand and completely devoid of any sign of human habitation between Amman and Wadi Musa. Over the years a few villages grew up along the route, the road was widened and improved into a dual carriageway of quite reasonable standard, and at length a "services" sprang up where tour coaches could break the long journey with a "comfort stop".

It was at this comfort stop that I was browsing through the books on offer while the others queued for the slightly odiferous toilets or satiated themselves with postcards and crudely-carved camels. In one book I found mention of the castle of al-Wu'ayra, complete with a photograph of the ruins and a warning that the bridge across the chasm into the castle was in a dangerous condition and must shortly collapse.

| |

| General view across the ruins of al-Wu'ayra castle. The entrance is out of shot to the left. |

Armed with a name and an idea of what to look for, I eagerly awaited our next trip to Petra. No one at the hotel reception knew the name - it may have been my pronunciation, of course, for I am no Arabist - and even the guide, foisted upon us by government decree, looked blank. Feeling frustrated I strolled out in the cool of the evening to sit on the terrace beside the swimmming and lo, there it was! Lining the skyline to the north was the distinctive shape seen in the book at the comfort stop.

Early the following morning I returned to the terrace with my camera and telephoto lens and looked again. Not only had the castle not faded away with the daylight like some phantom from the Arabian Nights, but through the telephoto lens I could make out the individual stones of the masonry that formed its ruined walls and towers.

With an hour or more in hand before breakfast, I set off towards the castle, but it proved to be further away than it had looked and the route over the eroded sandstone was far more difficult than I had anticipated. All that I accomplished was to get a couple of photographs from a different angle.

| |

| Detail of one of the surviving towers of al-Wu'ayra castle. |

Two years later, however, I was in Petra on my own, filming the Petra DVD that is on sale on this site, and had a hire car at my disposal. Petra closes at 4.00, so when I returned to the hotel after an exhausting day clambering around lugging my heavy camera and tripod, there was still plenty of daylight left. I hopped in the car and drove out of Wadi Musa in what I hoped was the right direction - the road to Little Petra.

Half a mile later there it was, still unreachably distant, but laid out below me like an architect's plan! The bridge had indeed collapsed (or if not collapsed, been reduced to such a state that I would not have ventured across it for a king's ransom!) but I could trace the circuit of the walls and identify the ruined towers. This was no Nabatean temple, but a genuine, unmistakable castle.

In fact, I subsequently discovered that it had been examined and excavated by Italians from the University of Florence, directed by Guido Vannini, though their findings had been scanty enough - a ruined apse from the castle chapel and a few fragments of fresco. The castle appears to have been built from smaller stones than was usual in Crusader work and was not proof against the weather and the occasional earthquake. (There is an excellent portfolio of photographs of both castles by Bob Reynolds on his website.)

| |

| You can see why this mountain was given the name of "el-Habis" - "the camel"! The Crusader castle is on the camel's hump. |

However in the meantime I had come across a reference in another book to a Crusader castle in the heart of Petra, on the summit of el-Habis, the camel-shaped mountain that rises above the rest house and museum. The following day, therefore, I shouldered my camera and trudged back into Petra.

I had three reasons for climbing up el-Habis. The first was the museum which is in a tomb about half-way up and which contains a number of fascinating things. Most visitors are content with the half a dozen objects on display in the Visitor Centre and depart without realising that there is a "proper" museum in Petra. The second was a suite of tombs known as the Hermitage. A rectangular courtyard has been sunk into the rock of the hillside behind el-Habis, around which half a dozen tombs have been created, cut into the sides of the courtyard. It is like nothing else in Petra.

The third and final thing, of course, was the Crusader castle. The other two are on the lower slopes of the mountain and the only guidance I had was that the castle was near the summit. Fortunately I noticed a well-maintained stone staircase running up from the Hermitage, and set off up it, despite the absence of signs.

Half an hour later I came to the top of the staircase and could have shouted for joy. There before me was a wall, running between two cliffs and blocking further access up the mountain. I hunted around and found a ruined gateway, which enabled me to climb higher.

| |

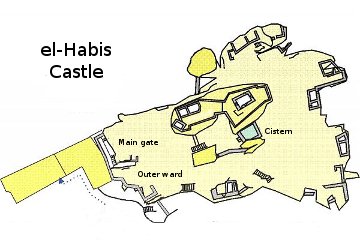

| The map shows the extent of the castle on el-Habis. The dark grey areas are walls; where there are no walls, the castle is defended by vertical cliffs. |

Now, on every hand, there were the ruins of walls, towers and buildings. What was even more significant was that walls had been built across every gully by whch an enemy might have crept up the mountain and gained access to the castle. In one or two cases, the gullies thus blocked had been further eroded over the years, so that the walls were suspended between the steep sides of the gullies, their bases hanging over nothing.

I had nearly reached the top of the mountain when I came to the impassable barrier. Clearly there had once been a path running from the small plateau where I stood, up the side of the precipitous slope to what must have been the keep of this extraordinary fortress. But in its zig-zag course, the path went far out over a sheer drop of several hundred feet to the base of el-Habis - and for most of its length, the path had been eroded to a couple of inches wide or less.

I am never comfortable with heights and gladly leave the climbing of Everest or the scaling of the Matterhorn to others. No doubt there are faun-like creatures, half man, half mountain goat, who would gallop up that track without a second thought. I, alas, am not one of them. I could trace the course of the path with my eyes, but to follow it was beyond me. A too vivid imagination pictured my foot slipping, the helpless scrabbling for purchase on the slope, and then the final plunge into oblivion over the edge. I took a last photograph and started back down again.

So now you know as much as I do and you could, if you were so minded, retrace my steps and identify the two Crusader castles in Petra - but I have one final secret up my sleeve! Why did the Crusaders build two castles in Petra? One would be extravagant enough in this howling wilderness, but two?

Hollywood always depicts mediaeval castles as crammed full of defenders - serried ranks of men-at-arms drawn up in the courtyard, bowmen filling every machiolation. The reality is that such a situation was extremely rare. The mighty castles of Edward I, situated in the heart of enemy north Wales, were usually held by no more than twenty or thirty men and sometimes by half that number.

One fateful Sunday in 1144, the garrison of al-Wu'ayra were at church, leaving only a couple of men to keep guard in the entrance tunnel. They idly watched the approach of half a dozen ragged villagers, perhaps speculating on why the peasants should be abroad on the day of rest, but not alarmed in the least.

They might have sat up straighter if they had known that the prevous night a party of Turkish soldiers had ridden into Wadi Musa and plotted with the Muslim villagers. It was these men, wearing their hosts' clothing, who now approached the gate while the rest of the band lurked out of sight around the corner.

It was all absurdly easy. A sudden rush, a quick flurry of daggers and the castle had fallen. The unarmed garrison were slaughtered one by one as they emerged from the chapel and the essential staging post of Wadi Musa was in Turkish hands. Communications between Aqaba and Kerak were cut, and the castle could serve as a forward base from which attacks on Kerak or Montreal might be launched.

William of Tyre tells us what happened next.

When it became known that the enemy had seized this fortress and had killed the Christians dwelling there, the king, although still very young, levied forces from all over the land and set out for it. ... The inhabitants of the country had already received news of our approach and with their wives and children fled into the fortress, the defences of which seemed to render it impregnable. For several days our forces exerted themselves in vain before the place. Volleys of stone missiles, repeated showers of arrows, and other methods of assault were tried with no result. Finally the Christians became convinced that, because of its fortifications, the place could not be taken. They therefore turned to other plans.

The entire region was covered with luxuriant olive groves which shaded the surface of the land like a dense forest. The inhabitants of the land made their living from these trees as their fathers had done before them. If these failed, then all means of livelihood would be taken away. It was decided, therefore, to root out the trees and burn them. It was thought that the terrified inhabitants, rendered desperate by the destruction of their olive groves , would either give up or drive out the Turks who had taken refuge in the citadel and surrender the fortress to us.

The plan was entirely successful. As soon as they saw their beloved trees cut down, the people changed their tactics and adopted others. On condition that the Turks whom they had called in were allowed to depart unharmed and that they themselves with their families should not be punished by death for ther wicked conduct, they restored the stronghold to the king.

So strong was the position of the castle that it held out until 1188 and according to some accounts was the last Crusader castle east of the Jordan to surrender to Saladin. However despite its strength, al-Wu'ayra suffered from one significant disadvantage: it was fairly low down and that made it difficult or even impossible to see the fire and smoke signals from Montreal and Kerak. The castle on el-Habis, on the other hand, was much higher up and had a clear sight-line to the north. It should be viewed as an outpost of al-Wu'ayra, though no doubt it was also a second line of defence, an inaccessible eyrie, so guarded by nature and the wiles of man that two or three men could have held it against a multitude.

Google Earth is a bit of a disappointment, for although the outline of al-Wu'ayra can be made out, it is not at all clear, and absolutely nothing can be seen of the el-Habis castle. In addition, the idiots who post photographs have scattered them all over the place so that every little shadow on the ground is labelled "the Siq" and pictures of the Khazneh can be found just about anywhere you click.

a safe passage This involved an hour of more of bargaining and the payment of a sum of money, which purchased us the services of a "guard", a decrepit gentleman as short of teeth as he was of wind. This worthy slept all day and, as my father discovered when he rose in the small hours to check on our sentry, all night as well, his blunderbuss propped against the wall some distance away.

In the morning my father requested permission to examine this ancient firearm and was apalled to discover that the barrel was almost completely choked with rust. It was borne in upon us that we were not hiring a guard but paying protection money. If we had refused, the younger men of the tribe, presently abroad poaching camels or committing banditry upon the highway, would have been summoned back to cut our throats by way of encouraging les autres.

Mind you, we were luckier than earlier travellers, some, at least, of whom had been obliged to battle their way into Petra. Only when the longer range and greater accuracy of their weapons had enabled them to demolish half a dozen verminous followers of the prophet did the remainder retire sulkily to allow the infidels free access to the ruins. Return

trudged back into Petra That is not strictly accurate. The stroll into Petra in the cool of the morning is a delight, no matter how often you do it. Even the first glimpse of el-Khazneh, gleaming through the narrow crack of the Siq, still takes my breath away - and I've lost count of how many times I've seen it. So I ought to say that I strolled briskly back into Petra.

Unfortunately the Nabateans, with no concern for tourists, laid out their city downhill from the hotels of Wadi Musa. The result is that the mile and a quarter out of Petra, when you are worn out from the climb up to the High Place and ed-Deir, is a slow uphill torture. (That is why, in our tour of Petra this year, we are allowing two days so that we can do the High Place one day and ed-Deir the next.)

What makes it even more galling is that the Siq is not the only entrance into Petra! Petra lies in a wide valley that runs north-south and although the southern end is closed by rugged cliffs and reached only via the Siq, the northern end is nearly a mile wide and rises in a gentle slope to the level of the surrounding countryside. Not only would a road be feasible, it actually exists - and when I was filming the Temple of Dusara I had to skip nimbly out of the way of a bedu driving a 4x4 and apparently late for work at the Visitor Centre, to judge by the speed at which he was travelling!

I long for the day when tourists will be decanted at the ticket office in the early morning, stroll into Petra through the Siq, view the ruins at their leisure and then, as the rocks radiate an oven-like heat from the noonday sun, sink gratefully into their air-conditioned coaches which have driven down into the middle of Petra to meet them. Return

destruction of their olive groves I doubt that Wadi Musa and Petra ever recovered from this episode of vandalism, for the trees that were cut down had held the soil together and kept it moist. Now the hot, dry sand took over and what were once fertile fields became sand-covered wastes. The Israelis, who are cheerfully burning and destroying Palestinian olive groves, might care to consider the long-term consequences of their vandalism. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2011