Dead Sea Scrolls Googled

I have always been slightly dubious about the rationale behind the banning of flash photography in museums. Back in the good old days, when photography was in its infancy, there were very good reasons for such a ban.

In those days the only means of producing a burst of intense light was to set fire to a pile of magnesium powder. You piled a scoop or two of powder on a bit of wood with a handle and a trigger. You held the wood up, you took the cap off your camera lens - shutters had not yet been invented - and you pulled the trigger. There was a quick flash that seemed to burn your retinas and you replaced the cap on your camera lens. You also, if at all possible, made a hasty departure.

Magnesium powder produced a cloud of thick, oily smoke that gradually settled, coating everything for a dozen yards around in a filthy black that took ages to remove!

Later, when photography was adopted by the masses, some enterprising individual shrouded filaments of magnesium in a glass envelope to produce the flash bulb. A later development was to have four such bulbs in a housing that automatically rotated to bring a fresh bulb into play - the flash cube. The light produced by these contraptions was not only white and bright, but it also lasted for an appreciable fraction of a second, making them the flash of choice for owners of SLR cameras whose shutters took an appreciable fraction of a second to cross the flocal plane.

By their very nature, however, flash bulbs were single use only, and popular tourist spots were frequently littered with discarded bulbs and cubes. As well as his heavy camera and its assorted heavy lenses, professional photographers crippled themselves carrying bags full of flash bulbs. I remember once seeing a photograph of the Great Pyramid by night, taken by a Life photographer - I'm pretty sure it was Life - who had placed several thousand flash bulbs on the layers of the pyramid and spent several days wiring them all together. The result was impressive, but I'm betting that he didn't spend the next couple of days gathering up the spent bulbs!

It was a great boon when some genius invented the electronic flash, which gave a short, strobe-like burst of light and which could be used again and again and again. No more bags full of bulbs, no more bulbs which failed to go off, no more discarded bulbs to be trodden underfoot and leave the ground littered with broken glass.

And that was where my gripe against museums came in, for electronic flash was so short that it seemed incredible to me that it could possibly cause any damage to objects that had stood in the unprotected deserts of Egypt or Assyria for several thousand years. I remember voicing my complaint to one museum curator who expressed sympathy for my point of view, but remarked that electronic flash was so new that no proper assessment of its potential for harm could have been done and therefore it was better to be safe than sorry - a position that I could but endorse.

I was interested, therefore, to read that Israel has permitted flash photography of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Don't bother packing your camera and heading for the Shrine of the Book, however. The permission was given to one man only, Ardon bar-Hama, a professional photographer of antiques, who was working for none other than the world's favourite search engine - Google. Mr Bar-Hama used a special flash fitted with an ultra-violet filter whose electronics had been manipulated to produce a burst of light one four-thousandth of a second long!

The result should bring long faces to conspiracy theorists everywhere. Five of the most important Dead Sea Scrolls are now available on-line - the "War of the Sons of LIght against the Sons of Darkness", the "Habakkuk Commentary", the "Temple Scroll", the "Community Rule" and, best of all, the "Great Isaiah Scroll".

The "Community Rule", also known as the "Manual of Discipline", sets out the way in which an ideal community was to be governed. There is dispute over the extent to which the rules it prescribes were ever put into practice, but many believe that it is the rule by which the Essenes of Qumran regulated their lives.

The "Temple Scroll" and the "War of the Sons of Light" are universally recognised as dreams that had very little chance of becoming factual. The "Temple Scroll" describes the construction and operation of a future temple that was cleansed of the improper rituals that made the Essenes so dissatisfied with the temple of Jerusalem. The "War" describes a highly ritualised war in which the ranks of the sons of light advance, retire and take rest breaks according to trumpet signals. It does not appear to have occurred to the author that the enemy - almost certainly the Romans - might have their own ideas about advancing and resting!

| |

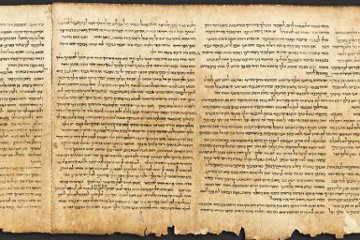

| A couple of columns from the Great Isaiah Scroll currently housed in the Shrine of the Book. |

However it is the "Great Isaiah Scroll" that is of most interest to me. Found in the first cave at Qumran in 1947, the scroll is 11" high and 24' long, which makes it one of the longest scrolls ever discovered. In addition, its 54 columns of text on 17 pieces of parchment, are in a remarkably good state of preservation. The scroll has been carbon-dated to either 335-324 BC or 202-107 BC, but a study of the writing leads to the conclusion that it was written between 150-100 BC.

Christians often boast that the Great Isaiah Scroll has never been translated "because it is identical to the book we have in our Bibles". It is a dramatic claim, but it is wrong on two counts.

In the first place, the scroll has been translated and you can even find portions of the translation on the internet. Quite why the individual concerned went to all the trouble, I do not know, because the text is essentially what we have in our Bibles!

Secondly, there are many differences between the Great Isaiah Scroll and the Hebrew version we have in our Bibles - which is the Masoretic text. The vast majority of these differences are variations in spelling, like the word "colour" misspelled as "color" or "travelled" as "traveled". Neither the pronunciation nor the meaning are altered.

There are a few added words, but I am not aware of any which significantly alter the meaning of any passage. We might compare the phrase "a big man" with "a great big man"; the added word "great" does not significantly alter the meaning we are trying to convey.

Conspiracy theorists have long claimed that the reason why there was such a long delay before the publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls was that they contained some secret information fatal to Christianity and which a cabal of scholars, monks and Vatican politicians was keeping from the public in order to keep a profitable racket going. Even the publication a few years ago of all the scrolls by Herschel Shanks - an action bitterly resented by the Israeli government but for which the world must be ever grateful - did not greatly impede the dedicated conspiracy theorists.

Now, however, five scrolls are on-line and more are planned for publication in the near future. It will be interesting to see whether the CTs will spend much time poring over the texts in search of the hidden verses that disprove Christianity. I suspect they won't for the simple reason that none of them can read Hebrew - if they were scholars they wouldn't be conspiracy theorists!

Those who have a particular interest in the Dead Sea Scrolls can view them at the URL given above. I notice that right-clicking on the image has been carefully disabled so that you can't copy and paste - a futile attempt to protect copyright when screens can be grabbed and saved to your hard drive. I have not done so - yet - but I reiterate my position: like all the world's treasures, the Dead Sea Scrolls do not belong to Israel nor to the Shrine of the Book. They belong to the world, and their placing in the public domain is long overdue.

a scoop or two of powder Manipulating the powder was a job invariably given to the apprentice, sometimes with unfortunate results. Many years ago I read a piece by Victor Blackman, then a contributor to Britain's Amateur Photographer magazine, in which he reminisced about his early days as a press photographer.

Apparently there was some civic service in progress, attended by all the good and fair in local society, all in their best clothes and uniforms, complete with decorations for men and hats for women. At the end of the service the multitude was to leave the cathedral via the great west door, led by the archbishop and in anticipation of this event the newspapers had sent down their photographers, who were clustered about the entrance, their cameras already focussed on the doorway. One or two enterprising souls were even perched on stepladders so as to obtain a better angle for their picture.

As the day was somewhat overcast, it was agreed that flash was necessary and the job of preparing the equipment was deputed to one of the apprentices. His superior, casting an eye on the sky and estimating the amount of ambient light, instructed him that one scoop should be sufficient. The apprentice, for reasons best known to himself, concluded that he should put one scoop for each of the photographers present and as all the photographers were concentrating on the door or on swapping tales of photographic derring do, he quietly heaped up a pile of magnesium powder that would have proved most useful during the recent unpleasantness in Flanders.

In due course the great doors creaked open and the robed vergers stood aside while the archbishop processed out, crozier in hand, mitre on head. Close behind came the lord-lieutenant and his immaculately turned out lady and a horde of wealthy businessmen, wealthy members of the upper classes and possibly even a foreign ambassador or two, all clad in starched white shirts and glossy top hats, and all eager to immortalise themselves in this new technology of film and print.

"Caps off," called the senior photographer and the assembled journalists removed the caps from their camera lenses and the apprentice took a firm grip on his bit of wood and squeezed the trigger.

The smoke slowly settled and cleared, to reveal a tangled heap of cameras, wooden tripods, fallen stepladders and swearing photographers who, irrespective of age or sex, were giving full vent to a wide-ranging and profane vocabularly. A short distance away stood the flower of the county, staring eyes peering out from faces that would have done credit to a troope of black-face minstrels, mitres, toppers and hats swept away by the explosion, clothing irredeemably ruined by the tendrils of oily black smoke that still wreathed about them. Return

one four-thousandth of a second Although the news report which drew Mr bar-Hama's activities to my attention spoke of this short duration with bated breath, the fact is that automatic flashguns cannot vary the brightness of the flash and therefore vary the duration in order to produce the correct exposure. My favourite flashgun produces a loud "pop" when aimed at something in the distance, but point it at a nearby subject and it goes of with a crisp "tic". I would have to look up the technical specifications, but I am pretty sure that at short distances it, too, produces extremely short bursts of light that would be very close to the stated figure for this special flash used by Google. Return

| |

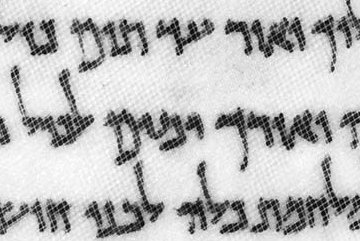

| Detail of the War Scroll showing the clear mark of the nylon mesh that protects the scrolls. |

can view them If you do - and if you zoom in - you will doubtless be puzzled by the regular pattern of white lines that disfigures the letters in a cross-hatch pattern. The explanation is very simple.

Some years ago the Diggings group was excavating at the Western Wall and as a "reward" for our labours in a particularly hot summer, we were taken on a guided tour of the Rockerfeller Museum basement. Down there we saw the reconstructed fragments of a scribe's desk from Qumran, a collection of silver coins discoloured and misshapen by the fires that destroyed Jerusalem in AD 70, and a couple of charming ladies messing around with scroll fragments.

We sought an explanation for their activities. Apparently the first scholars to study the scrolls had sought to protect them by sellotaping them to glass plates. It doubtless seemed a good idea at the time, but if you have ever repaired something with Sellotape, you will be aware that after a relatively short period of time the tape degrades, cracks and peels off, leaving behind a solid residue of what used to be adhesive!

This is what had happened to the priceless fragments and now the museum conservators, fearful lest the sellotape discolour and possibly even harm the bits of leather, were carefully removing the sellotape (and trying to remove the residue) and placing them between two layers of very fine nylon mesh held taut in a frame. The idea was that the inert nylon would not harm the ancient leather, the fine mesh was almost as transparent as glass, and researchers would be able to examine the fragments without touching the leather.

This, then, is the origin of the white lines in the picture: it is the nylon mesh which was not removed when the scroll was photographed. Over most of the scroll it makes little difference, but if you look down the bottom of the first page of the "War Scroll" you can see where the writing is damaged and attempts to decipher it are distinctly hindered by the mesh. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2011