The Great Bristol Box Mystery

Ur, the capital city of the Sumerian civilisation is inevitably linked with the name "Sir Leonard Woolley", who conducted excavations there during the 1920s and 1930s. Largely forgotten by the popular media these days, at the time his work in Ur was front page news because of the amazing finds he made and the sensational claims he touted to the press.

Among the finds were the great ziggurat of Ur which, though hardly unknown, was cleared and studied by him to an unprecedented degree; the various treasures such as the golden helmet of Mes-kalam-dug and the "Ram caught in a thicket"; and the incredible "Death Pits" of Ur, of which more later. Among the claims was the infamous "Flood Pit", which Woolley declared was archaeological evidence for Noah's Flood, and the "House of Abraham", which was nothing of the sort, but merely a wealthy merchant's house from what was believed to be the period of Abraham.

At one point during the excavations, which were sponsored by the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Woolley decided to dig a trial pit right down to bedrock, simply to give himself an indication of how old the city of Ur was. In other locations the excavators might dig a trench that started at the foot of the tel and extended to its top, but there was no distinct tel for Ur, so Woolley set his workmen to dig at a spot selected more or less at random.

His pit was an enormous 75'x65' and at first his workmen toiled away enthusiastically, no doubt hoping that Woolley was hot on the trail of yet more rich tombs, from which they could expect copious baksheesh. They were to be disappointed and eventually, after several weeks of unremitting labour, they gave a sigh of relief when their hoes encountered sterile clay. They had reached the bottom, the end of man's constructions, the base on which the original city of Ur was built.

The trouble was that when Woolley measured the depth of the pit, he found that it was a considerable distance more shallow than he had expected. Somewhat puzzled - and much to his workmen's chagrin - he ordered them to continue digging. Days went by as they hacked at the clay, breaking out huge chunks of it and loading them into baskets which other workmen carried on their heads up the steep stairway out of the pit and over to the dump.

| |

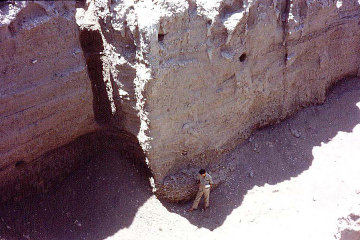

| In this picture, taken in 1967, I am standing at the bottom of Wooley's great Flood Pit, which I think was more than half filled in with wind-blown sand by then. (And yes, I did have a bandage on my arm!) |

Grumbling grew in intensity, because Woolley had instituted a system of bucksheesh based on the finds made by his workmen - and there were no finds in the sterile clay through which they were digging. Woolley was sympathetic but unrelenting and the workmen must have thought they were heading for Australia or the Underworld - whichever came first - when suddenly, 64' below ground level, the clay ended after 11' and they found themselves in ordinary soil again and even better, there were bits of pottery and the hope of bucksheesh to come.

The discovery was not entirely unexpected, for Woolley had dug a similar - though much smaller - shaft the previous year and excavators at Kish had also made a similar discovery of a thick layer of water-borne clay covering the very earliest deposits on the site. However it was the interpretation that puzzled both Woolley and the Kish team. He mentioned the conundrum to some of his colleagues, who scratched their heads and expressed bafflement.

In those days of leisurely travel it was not unknown for excavators to be accompanied by their wives - Agatha Christie, for example, accompanied her husband Max Mallowan - and Woolley was accompanied by his wife, Katherine. She happened to pass just then and almost facetiously he put the problem to her. Almost casually she replied, "Well, of course, it's the Flood." Woolley immediately saw the potential for publicity and contacted the newspapers to say that he had found evidence for Noah's Flood.

Even at the time he must have known that it was no such thing. His colleagues at Kish had found the evidence for three separate floods in Early Dynastic I, II and III, whereas Woolley's flood was in the al-Ubaid period. A couple of years later excavations at Shuruppak discovered a flood layer that separated the late Protoliterate and Early Dynastic I periods. Woolley had not found Noah's Flood, merely one of many local floods.

That did not prevent the press - and various Bible scholars who should have known better but were ignorant of archaeology - from concluding that Noah's Flood was a large but local deluge and not at all the world-wide flood described by the Bible.

Woolley's discovery of the Death Pits of Ur was on much more certain ground, for the excavation was carried out to the highest standards of the day. In fact, when Woolley suspected that he was near an ancient cemetery in the first year of his dig, he deliberately moved his workforce elsewhere, because the workmen were not yet trained enough to dig with the care and attention necessary. The result was that when his men were sufficiently experienced and trustworthy and he returned to the cemetery, the results exceeded all expectations.

There were, of course, any number of individual burials, but it was the Death Pits that attracted and held public attention. Deep pits entered by a ramp with a burial chamber at the bottom, the pits held as many as 76 bodies laid out in careful rows on their floor. As well as the human skeletons, there were also the bones of sacrificial and food animals and of horses that drew the cumbersome wagons that passed for chariots in those days.

| |

| A modern photograph of the entrance to one of the Death Pits of Ur. |

There was no sign of injury on the bodies and Woolley's conclusion was that the victims were willing participants in some ritual of mass suicide. He describes in considerable and not entirely fanciful details how the royal servants, male and female, marched down into the pit, soldiers with their weapons, harpists with their harps, female servants with their finery, and grouped themselves in accordance with the orders of some master of ceremonies. When all was ready pots of poison were circulated among them and, having drunk, they lay down peacefully to die. When life was extinct, then the pit was filled in, burying the treasures and the bodies in one huge communal grave.

Woolley's attention to detail was astounding. In one Death Pit he discovered a female skeleton with a lump of metal on her hip which, when cleaned and examined, proved to be long silver tape tightly coiled and it was the tightness with which it had been rolled up that preserved it over thousands of years. It was then that Woolley recalled noticing a purple stain on the skulls of other women in that particular pit and surmised that the stain was the result of the oxidation of the thin silver strip. In his book he describes how the other women adorned their hair and heads with the silver ribbon but one lady was late for her own funeral and by the time she reached her appointed place the others were already taking their cups of poison. She had no time to retrieve the silver ribbon from her bag and put it on her head and so it remained coiled up on her hip until her tardiness was discovered by Woolley.

Unfortunately, despite his skill and care, the techniques that modern excavators take for granted were neither known nor dreamed of in Woolley's day. Although he recorded them in detail, Woolley did not keep many of the skeletons he discovered, and as for preserving samples of the earth for pollen analysis or any of the other investigative techniques that are available today, it simply wasn't done. As a result, the discovery in 2014 of long-lost items from Woolley's excavations caused considerable excitement in archaeological circles.

| |

| The box found on top of a cupboard, which contained objects from Sir Leonard Woolley's excavations at Ur. |

Bristol University, in western England, was having a clear-out. Quite why it was doing so has not been made public: perhaps there was a new director and, as is well known, new brooms sweep with particular efficiency; perhaps it was merely that someone somewhere decided that the place was a mess and needed tidying up. Whatever the motivation, the clear-out was taking place and the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology was not immune.

In their determination to be thorough, the "clearer-outers" not only emptied cupboards but even climbed up on chairs to remove the layers of mildewed paper, dust and dead spiders that tend to accumulate in such places. One of these diligent individuals discovered a rather battered wooden box on which was inscribed, "Junior Army and Navy Stores Ltd" and an address.

| |

| Some of the objects found in the box, which include pottery and fragments of bone. |

Gingerly, in case the box contained explosives left over from the war, the diligent one poked at the crumpled brown paper that filled the box and wrapped whatever was within it. In doing so he discovered a number of hand-written index cards on which he was able to decipher such words as "Pre-dynastic", "Sargonid" and "Royal Tombs". With growing excitement he unwrapped the brown paper to reveal small cardboard boxes - the same sort of boxes we use in our excavations today - on which were written brief notes such as "Contents of cup in DG 1054" or "Contents of old strainer DG 800a". In the boxes were fragments of bone, pieces of pottery and a number of unidentified substances and objects.

| |

| Dr Alexander Fletcher (left) and Dr Tamar Hodos (right) pack the items before sending them to the British Museum in London. |

The authorities in Briston University have handed the box and its contents over to the British Museum where, no doubt, it will be intensively studied. However Dr Tamar Hodos, senior lecturer in archaeology at Bristol remains puzzled. "The environmental remains themselves were published in 1978 in Journal of Archaeological Science. The authors of that study were based at the Institute of Archaeology, London, and at the University of Southampton, and none of them had any known connection to the University of Bristol that might explain how the material came to reside here. If anyone can shed light on this mystery, we would love to hear from them," he says.

a system of bucksheesh Fairly early on in his dig Woolley became aware that items of value were being smuggled away in the pockets of his workmen, to be sold to local antique dealers or, in the case of gold, sold to the local gold smiths. He could, of course, have ordered searches and floggings for offenders - which is what the Germans with whom he worked in northern Mesopotamia did - but he opted for a gentler approach. He let it be known that he would pay for any finds and the price he offered was just slightly higher than what the local dealers and smiths were offering. The faces of his workers as they realised that they had missed out on a better price were comical and many promptly went to the dealers and bought back the items they had previously sold. For the next few days an astonishing amount of gold beads and other objects were "found" by the delighted workmen, a level of discovery that was never equalled again, though there was no further pilfering from the dig. Return

no sign of injury In fact, CT scans conducted by Penn University Museum in 2010 on a male and a female revealed that both had been killed by blows to the head. Needless to say, CT scans were not available in the 1920s! There was also evidence that the bodies had been treated with heat and mercury, probably to preserve the bodies during the period leading up to the funeral ceremony, before being laid out in rows for burial.

On a completely unrelated note, while researching this story I consulted the Penn University website and discovered that they offer to turn your initials into cuneiform. If you would like to have your initials in cuneiform script - for your personal seal, of course - then you can visit the Penn University website and they will be happy to oblige free of charge. We make no representations as to whether Hammurabi would be able to recognise your name from the output. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2014