Minoan Myths?

When Sir Arthur Evans uncovered the amazing ruins of Knossos, on the island of Crete, he not only brought to light a civilisation that had been forgotten by history, but he also provided a shock for those who made a grubby living out of "debunking" ancient historical records.

| |

| A restored portico in the Minoan palace of Knossos. |

According to Greek sources, at one time the kings of Crete had been so powerful that they ruled over mainland Greece, extorting a regular tribute of seven youths and seven maidens from the people of Athens. These unfortunate young people were taken to Crete and fed to the Minotaur, a horrible creature half bull and half man that had resulted from an unnatural affair between a mysterious divine bull and the wife of the king of Crete. This imposition only ended when Theseus, son of the king of Athens, tricked his way into the Labyrinth where the minotaur was kept and killed the monster.

That was one version of the story and it was easy for the debunkers to mock its claim that union between a woman and a bull could result in a birth and its account of a fabulous labyrinth. There were other, less incredible, versions in which the killing of the Athenian young people was revenge for the death of the Cretan crown prince, killed by an Athenian mob who were jealous of his successes at the Panthenaic Festival.

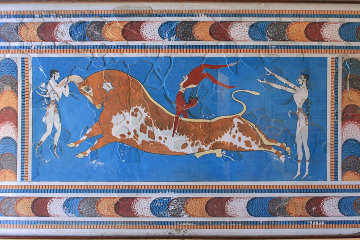

| |

| Some have suggested that the Minoan sport of bull-leaping may have given rise to the legend of the Minotaur. |

While scholars argued over whether the minotaur was a "solar personification" - whatever that may be - or whether the story was based in some way on Baal worship (!) they entirely lost sight of the historical fact that Crete had at one time been powerful enough to impose its will on Athens. Evans' discovery that Crete did indeed have a powerful and vibrant civilisation was a surprise and an unwelcome shock as pontificating professors realised that the ancient "legends" were based on historical truth.

Not that Evans was entirely free from his own theories and prejudices. In the course of his excavations he noted that the pottery and other artefacts he found bore a vague resemblance to things discovered in Egypt and Libya. There was clear evidence that Crete had been occupied by Neolithic peoples who had come from Europe, but this was a time when "artists' depictions" still showed the Neolithic as shaggy, beetle-browed, bow-legged half-apes. Just as man had originally come from Africa, so civilisation must have come to these primitive Neolithics from Africa and Evans had no hesitation in proclaiming that the Minoans hailed from north Africa and had imposed their imported culture on the original inhabitants of the island.

Not everyone accepted this theory. Prejudice against "primitive" Africans ensured that many were apalled by the idea that they might once have been more cultured than Europeans of whatever era. Instead of focussing on the similarities between artefacts, these scholars pointed out that the Minoan paintings showed distinctly fair-skinned people with European features and hair, and so the debate raged on, generating more heat than light.

Onn the whole, the Evans theory was on the losing side. Excavations at places like Catal Huyuk in Turkey conclusively demonstrated that the Neolithic people were quite capable of sophistication and culture. They are now widely hailed as Europe's first farmers, bringing the benefits of agriculture with them as they or their culture spread. In addition, Evans' dates for the Minoan civilisation came under scrutiny and people realised that instead of Africa influencing Crete, it may well have been Crete influencing Africa! Minoan pottery was highly prized in ancient Egypt and in Palestine.

| |

| A collection of bones from the Minoan period found in the Lassithi cave in eastern Crete. |

Now Dr George Stamatoyannopoulos, professor of medicine and genome sciences at the University of Washington, has investigated the mitochondrial DNA of the ancient Minoans. DNA samples were taken from 37 skeletons found in a cave on the Lassithi plateau and analysed and the results show conclusively that the Minoans were of Indo-European stock. There was virtually no correlation between the Minoan mitochrondrial DNA and that of Africans (except insofar as all humans are similar to one another).

Whether this will put an end to the debate remains to be seen. There is nothing scholars love so much as picking holes in the work of other scholars and no doubt someone will be along shortly to claim that the Lassithi skeletons were not typical Minoan or something. This, of course, is how science progresses and healthy debate is always to be encouraged.

Nevertheless I think there is one important lesson that can be learned and that is that we should not ignore ancient documents. Even the most fantastical frequently contain a kernel of truth and sometimes even more than a kernel.

Take, for example, the fabulous account in the Bible of how the Assyrian king Sennacherib attacked Jerusalem and was handily driven off when "the angel of the Lord" smote 185,000 of his men.

It would be very easy to dismiss the whole thing as "legend" and completely beyond the realms of possibility and there have been critics who have done just that. Yet among the earliest discoveries from Assyria were the Lachish Reliefs, depicting incidents in Sennacherib's campaign, showing that the Bible is correct in stating that the Assyrian king attacked Israel.

| |

| On the left you can see where the foreleg of the bull was chipped away by Layard. |

Layard was reliant upon fairly primitive methods to transport the stone bulls and other objects from the mounds where they were discovered to Basra, where they were loaded aboard a British warship to be brought back to the British Museum. When confronted with an usually large bull that had a panel of cuneiform writing between its legs, for reasons that we do not know, Layard felt obliged to preserve the inscription - even though this was 30 years before cuneiform could be read and many still regarded it as little more than decoration!

That panel, now in the British Museum, contains an account of Sennacherib's campaign in which, after listing all the cities he had destroyed and the vengeance he had taken on those he perceived as rebels, the Assyrian king concludes rather lamely "and I shut Hezekiah up in Jerusalem like a bird in a cage" - unusual leniency for the leader of the rebellion who actually had Padi, pro-Assyrian king of Ekron in his dungeon in Jerusalem at the time!

Curiously, Herodotus also records that Sennacherib came to grief when he attacked Palestine and Egypt, though his tale is that an army of mice devoured all the bow-strings and leather work, leaving the Assyrians weaponless, and this came about through the intervention of the Egyptian gods. Most scholars accept that the two stories refer to the same incident and some go so far as to claim that as mice and rats are carriers of plague, it was really an outbreak of disease which devastated the Assyrian army.

In other words, instead of being pure fantasy, the stories in the Bible and other ancient sources almost certainly have an element of fact in them. Instead of dismissing the stories out of hand, the intelligent response is to seek to discover the kernel of fact - and when we do that, we find that the Bible is as reliable as any other ancient source and more reliable than most!

In addition, we should beware of dismissing too much as exaggeration or fantasy. Some have objected to the Biblical account of Sennacherib's disaster on the grounds that while Assyrian armies commonly numbered in the tens of thousands, 185,000 is just too incredible a figure to be taken seriously. The fact is, however, that the problem may lie with translation rather than the Biblical author.

Others better acquainted with Hebrew than I am have pointed out that the word "aleph", usually translated as "thousand", can also mean "clan" or "army unit". The loss of 185 squadrons may well have been sufficient to cause Sennacherib to abandon the siege of Jerusalem, particularly after the losses he suffered in the attack on other cities such as Lachish. In addition, it is quite possible that both the Jews and Sennacherib himself may have seen this loss as a divine intervention and reacted accordingly - and who is to say that they were wrong?

Those who believe in God have no difficulty in accepting that He can intervene in dramatic fashion and even those who don't believe in God can nevertheless respect the Bible as a reliable source of historical information as well as a guide to the ideas and beliefs of people at that time.

© Kendall K. Down 2014