Axes without Thongs

It seems like the boffins will have to abandon yet another cherished idea!

| |

| No shaggy coats, but still demonstrably primitive - an artist's impression of a Neolithic family. |

It is not all that long since Neolithic Man was depicted as an ape-like creature with shaggy pelt, louring eyebrows and protruding jaw, shambling along with either a wife's hair or a primitive spear clutched firmly with one over-long arm. Primitive, of course, is the operative word, for who else but a primitive would use a stone axe or chip out flint arrow heads?

The first real dent in this picture of the Neolithic came when Kathleen Kenyon excavated Jericho, for there, at the very bottom of her deepest trench, lay a large stone tower of stone, Neolithic, but a far more impressive fortification than any of the mud-brick walls which succeeded it from the increasingly sophisticated ages of Bronze and Iron. So redoubtable was this wall that the second time we saw it we overheard a guide conducting an American family around, informing them that it was Roman.

| |

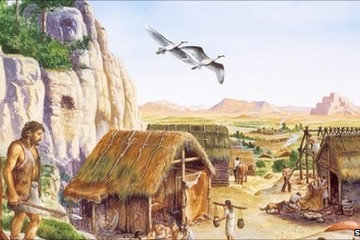

| A rather more realistic artist's impression of a Neolithic settlement - notice the ziggurat in the background! |

"Gee, honey!" the enthusiastic gentleman from the western side of the Atlantic cried. "Fancy that. A lil' old Roman tower. Look, children. That was built by the Romans who crucified Jesus!"

For a number of years archaeologists stirred uncomfortably and changed the subject if anyone questioned them about the Neolithic, but then came the remarkable discoveries at Catal Huyuk, where an entire Neolithic city was uncovered, revealing not just impressive buildings, but evidence of a sophisticated economy based on farming and trade. Even more unexpected, these "primitive" people quite clearly had a complex system of beliefs, as evidenced in the temples and ritual buildings the archaeologists discovered; buildings, moreover, which were decorated with painted patterns of an intricate and masterly design.

This prompted the archaeologists to take another look at the Neolithic skeletons in the various museums and they discovered, to their surprise, that the skeletons were not covered in shaggy coats of fur, nor where the eyebrow ridges unduly prominent and even the arms were no longer than those of any other human.

Somewhat reluctantly the boffins quietly discarded their beloved "artists' impressions" showing cavemen who were half-ape and began to redraw these impressions to show figures that were recognisably human. Instead of crouching fearfully around a fire on the open savannah while wolves and hyenas prowled threateningly in the background, our Neolithic family were now engaged in artistic pursuits, painting decorations on the walls, spinning and weaving cloth or grinding grain into flour on stone querns. One or two might even have been playing on flutes!

| |

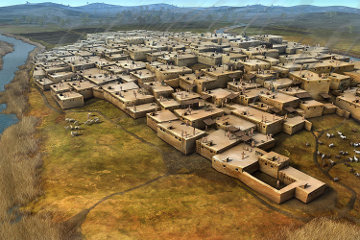

| Catal Huyuk Neolithic site is a substantial city with clear evidence of urban design. |

There was, however, one concession to earlier times that the archaeologists were loath to forsake. Somewhere in the picture, either clutched in the Neolithic hunter's hands or tucked into the Neolithic artist's belt, was a stone axe consisting of a piece of flint wedged into a split stick and bound in place with leather thongs.

But now it appears that even this cherished fantasy will have to be discarded, for Danish archaeologists excavating at Rodbyhavn on the island of Lolland, have discovered an axe complete with handle.

The excavation is a "rescue dig", clearing the way in preparation for a tunnel that is to be built between Lolland and the nearby German-owned island of Fehmarn. As you might expect in a coastal site, the excavators uncovered an ancient fish trap made of wooden stakes hammered into the sea bed, where the anaerobic conditions in the heavy clay shut out the oxygen and kept the stakes from decaying.

An unexpected discovery was a footprint left in the clay by one of these Neolithic fishermen, but that was not the only thing left behind by these somewhat careless workmen. The archaeologists found a paddle - and where there is a paddle there must be a canoe to be paddled, though that has not yet been found; there were a couple of poles that were thicker towards the middle and notched at the thinner ends, which the archaeologist identified as bows. Either these Neolithic people hunted deer and other animals when they weren't fishing (or, of course, fished when they weren't hunting) or they fished with bow and arrow instead of line and hook or nets.

The archaeologists also found a number of short but hefty pieces of wood with rectangular holes at one end. Nicely polished and rounded, they might have been clubs for subduing particularly obstreperous fish, though the purpose of the holes was unclear.

And then the archaeologists found another of these puzzling pieces of wood, only this one was sticking vertically out of the former sea bed. Gentle tugging failed to dislodge it, so out came the scalpels and trowels and the archaeologists began to carefully dig away the soil that imprisoned the piece of wood.

Whether it was normal practice or the archaeologists were just lucky that this piece of wood was on the edge of a square, I do not know. What I do know is that they carefully cut away the soil to expose one side of the piece of wood - and I am sure that with the benefit of hindsight they are devoutly grateful that they took such care.

| |

| The Rodbyhaven stone axe in its setting. The hole in the clay, later filled with coarser detritus, is clear to see. |

In the first place, the stratigraphy clearly showed that the piece of wood had not been just rammed into the clay, but a hole had been dug that had filled up with coarser material around the buried axe. In the second place, they discovered a stone axe-head carefully fitted into the rectangular hole - and not a leather thong in sight!

"Finding a hafted axe as well preserved as this one is quite amazing," declared Soren Anker Sorenson, an archaeologist from the Lolland-Falster Museum. He suggests that the axe was deliberately buried in the seabed as part of a ritual, perhaps as a thank-offering for some reason - the completion of the fish trap?

The interesting thing is that as he points out, a stone axe would be very useful for cutting the the wood for the stakes of the fish trap or shaping the paddle, but it would be even more useful for cutting down the forest that covered the land to clear space for farming. Here, then, we have farmers who do a bit of hunting or fishing as relaxation as much as to supplement their diets.

As for the primitiveness of using stone tools - just recently we purchased a newer, sharper kitchen knife than any we have used before. Guess what it is made of? Ceramic, which, when you come down to it, is just a fancy, man-made stone. As a book I read pointed out, it is easier and faster to re-sharpen a flint axe or blade than it is to re-sharpen a metal tool and before the days of hardening, the flint tool kept its edge longer than the metal tool in any case.

As the Neolithic woodsman straightened up from putting a new edge to his flint axe and looked pityingly at his Bronze Age counterpart as he, for the umpteenth time that morning, painstakingly whetted his tool, I wonder who felt superior to whom?

Neolithic - primitive? No, just sophisticated enough to choose the easy option.

© Kendall K. Down 2014