Hymns Ancient and Modern

| |

| The Delphic Charioteer, one of the earliest bronze figure statues in Greece. |

If you do your homework, it is easy to go round a museum and be waiting by the exit while those who haven't are still peering into glass cases in the vague hope of finding something interesting - but as they don't know what they should be looking for, they are usually disappointed. Of course, there are the occasional moments of serendipity when they come across something that they recognise or which picques their imaginations. Mind you, serendipity can strike even the best prepared, which is what happened to me in the museum at Delphi.

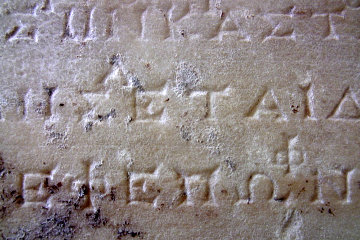

I knew about the famous charioteer, I expected to find the carved panels from the various treasuries, I was on the look out for some of the treasures which had survived the centuries, and I duly found and photographed all those things. Of course I did keep my eye out for anything I wasn't expecting, but I was less than thrilled by the cases full of broken stones and shattered pottery; see one red and black pot and you've seen 'em all, about summed it up. When I saw a couple of fragments of stone panels covered with closely packed Greek letters I almost passed them by, but the little card giving information was there so I snatched a quick glimpse at it in passing - and stopped dead.

The panels, so the card said, were the remains of Delphic Hymns and could be dated to between 138 BC and 128 BC - though more recent study suggests that both were from 128 BC and were written for the Athenian Pythaides. That was moderately interesting - as a Christian I'm rather keen on hymns and hymn-singing, and though these were heathen hymns, Christian hymns grew out of that soil and probably drew their inspiration from the poetry and music of ancient Greece.

The thing that really made me sit up and take notice, however, was the statement that these were the earliest examples of musical notation from antiquity.

| |

| A close-up of the Delphic Hymn, showing the letters between the lines which form the melody. |

I looked at the broken stones again. I play the piano, so I am very well acquainted with the familiar five line staves of the treble and bass cleffs. There were no such lines here, but when I looked closely I spotted that between each line of writing were an assortment of letters. I might have assumed that they were corrections inserted into the text, so I was grateful for that information. Mind you, it was fairly useless information to me, because I didn't understand the notation - it was as much of a sealed book to me as our familiar staves might be to you.

I did know that the ancient Greeks played on a kithera, a four-stringed harp whose strings were tuned at the intervals tone-tone-tone-semitone. On a piano, that would be the equivalent of C-D-E-F. Curiously, our modern scale consists of two kitheras end to end, so to speak, for the piano's G-A-B-C is again tone-tone-tone-semitone. In other words, our modern scale of - say - C-natural is a direct descendant of ancient Greek music.

This heritage probably explains why Arabic music, which uses a different scale, sounds so odd to us. We consider it inharmonious, simply because it doesn't conform to the ancient Greek scale on which we have been brought up.

Not that we would have totally appreciated ancient Greek music. Whereas we talk about major and minor scales, the ancient Greeks had what they called "modes". For example, if you go to your piano and start on F, then go up to the next F without playing any of the black notes, you will have played a scale in what the Greeks called the "Lydian Mode". On the other hand, if you start on D and play up to the next D without any black notes you will have played the "Phrygian Mode". There were seven modes; our scale of C-major was known to the Greeks as the "Dorian Mode". (If you don't happen to have a piano handy, look these various modes up on Wikipedia and you will find a clickable link which will play them to you.)

The different modes were supposed to evoke different emotions in the listener. The "Misolydian" was suitable for laments, the "Lydian" was relaxed or even effeminate. You will be pleased to know that the "Dorian" - our natural scale - was regarded as manly, virile and warlike!

Just like modern concert-goers, ancient audiences were expected to be familiar with the different modes and to react accordingly. Plutarch, in his essay "On Listening" records an incident involving the playwright Euripedes.

"Once, when the poet Euripides was prompting his chorus in a lyrical ode he had composed, a member of the chorus laughed. Euripides said, 'It is only your insensitivity and ignorance that make you laugh while I am singing in the Mixolydian mode.'"

Exit one very discomfitted chorister!

If you go to Wikipedia you will find a link on which you can click to hear the first of the Delphic Hymns, played on a computer. Frankly, I don't think it would have made "Top of the Pops", it is not chart topping material - but perhaps that is just our modern tastes. The ancients had very different attitudes: for example, flute playing was not only supposed to stir the hearers into a frenzy, but it actually did. If you want to imagine Pericles or Aristotle head-banging and raving down at the Athens disco, it would be to the sound of a flute-girl, not some hairy bloke with an electric guitar.

Because of the fact that they stirred men to a frenzy - and there was no telling what went on with men in that condition - flute girls were regarded as no better than they should be and were, in consequence, very popular at parties. Celsus, in "On the True Doctrine, his devastating (though often misplaced) critique of Christianity, reported, "I have heard that before their ceremonies, where they [the Christians] expand on their misunderstanding of the ancient traditions, they excite their hearers to the point of frenzy with flute music like that heard among the priests of Cybele."

| |

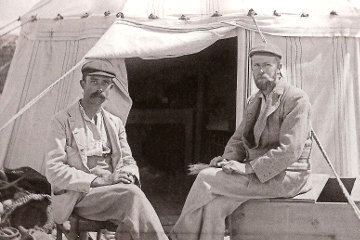

| Grenfell and Hunt sitting outside their tent during their excavations of Oxyrhynchus. |

The other day I came across a reference to Oxyrhynchus 1786, a papyrus now in the Sackler Library, Oxford. It was discovered in 1918 when Bernard Grenfell and Arthur Hunt, who went out to Egypt specifically to look for ancient papyrii. Oxyrhynchus was known to have been a centre for Christianity, so it was a safe bet that there would be ancient manuscripts to be found there, but what the two men could not have foreseen was that their discoveries would not be in some well-preserved ancient library, but in the town rubbish dump.

To us, papyrus is an exotic and precious substance; to the ancients it was as ordinary as paper - it was their paper! It may not have been as cheap as our machine-processed paper, but it was almost as ubiquitous. Governments used huge quantities of it in their civil services for things like tax and census records, playwrights and authors wrote on it, artists drew on it and schoolboys doodled on it.

Fortunately it was expensive, with the result that people never threw the stuff away until it was worn out. If you had a book of Menander's plays or Euclid's theorems and the cover was missing and some of the pages were falling out, then you tore bits off the remaining pages to use as Post-It notes or you rubbed as much of the previous text off with a pumice stone and wrote love letters on the pages. Only when the papyrus was too scribbled on to be further written on or too thin to be erased again did you throw it out - but in somewhere dry like Egypt, the scraps of papyrus never decayed.

Grenfell and Hunt found that the ancient city was surrounded by mounds of rubbish and every one of those mounds was positively bulging with pages and scraps of papyrus. Grenfell complained that "The flow of papyrii soon became a torrent. Merely turning up the soil with one's boot would frequently disclose a layer." For the next ten years the two men spent each winter in Egypt and the rest of the year back in Oxford, translating and arranging all the scraps of papyrus they had found.

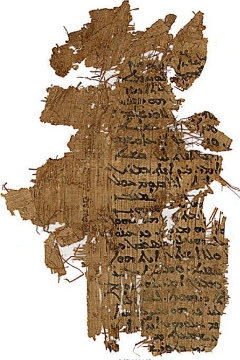

Oxyrhynchus 1786 was one of these papyrii, but unlike the fragments of Sappho or the thrown-out tax receipts, it turned out to be a Christian hymn and, what is more, a hymn with musical notation attached. Once again, it means nothing to me - hardly surprising - but once again there are scholars and experts who can make sense of it. Some have claimed that it lies behind the English hymn, "Let all mortal flesh keep silence". If so, all I can say is that the translator, a man by the name of Gerard Moultrie, took rather a lot of liberties with the original.

| |

| Oxyrhynchus papyrus 1786, on which is written the words and music of the earliest Christian hymn to be preserved. |

. . . together all the eminent ones of God. . .

. . . night] nor day (?) Let it/them be silent.

Let the luminous stars not [. . .],

. . . [Let the rushings of winds,

The sources] of all surging rivers [cease].

While we hymn Father and Son and Holy Spirit,

Let all the powers answer, "Amen, amen,

Strength, praise, [and glory forever to God],

The Sole Giver of all good things.

Amen, amen."

You can find an audio file of modern Greek Orthodox worshippers chanting a version of this hymn on the paperthinhymn website

© Kendall K. Down 2014