The Bactrian Princess

| Persian Gates | 30 42 30N 51 35 55E | A modern road snakes through the narrow pass which cost Alexander a month while Darius rearmed. |

| Bactria | 38 20 57.44N 63 42 11.84E | This wide valley was the heartland of ancient Bactria. |

| Ancient Amphipolis | 40 49 12.70N 23 50 50.15E | The excavations and part of the late city wall are clear to see. The Lion of Amphipolis is on the south bank of the river south of the city. |

| |

| The narrow defile of the Persian Gates, looking towards the Persian ambush. |

When Alexander the Great defeated the last Persian army at the Battle of Arbela, fought a short distance to the east of the ruins of Nineveh, the Persian king Darius fled towards the north-east, intending to raise another army and continue the struggle. Alexander, however, headed for Babylon and then the Persian capital of Persepolis. Along the way he fought skirmishes with the Uxians, who held a defile for personal profit, and Ariobarzanes, who held another narrow pass known as the Persian Gates, from patriotic motives. Both were defeated decisively, though the latter battle caused Alexander more casualties than the rest of the invasion of Persia!

Alexander occupied the Persian capital, Persepolis, and remained there for five months while his men looted the place. The treasury alone contained more than 50,000 talents of gold (the equivalent of 538 billion dollars in today's money). Unusually, although the city surrendered peacefully, Alexander allowed his men to treat it as a capture city, loot its wealth, kill the men and enslave the women and then, as a final mark of disgrace for the Persian empire, he ordered that great royal palace burned to the ground.

| |

| This is a photograph of the Persian Gate in winter. The gap through which the modern road passes was cut in the 1990s. Before that the only passage was along the stream bed on the right. |

By this time Darius had retreated to Bactria, which today is northern Afghanistan, around the town of Mazar-i-Sherif. Bactria was ruled by a satrap or governor named Bessus, who was a distant relative. Alexander chased after the Persian king, pursuing him into the far south-east of Persia. For reasons that have never been adequately explained, Bessus decided to murder Darius, though the deed was botched and Darius was still alive when Alexander caught up with the cart in which the dying king had been abandoned.

Bessus then proclaimed himself king, which meant that he had to be eliminated. He retreated to his power-base in Bactria and Alexander followed him. Later that same year Bessus was handed over to the Greeks and tortured to death, an action which was intended to show the world that Darius was not killed by the will or order of Alexander. Darius was, in fact, given a state funeral by Alexander, which was also intended to declare Alexander's innocence of his death.

Having come so far north, Alexander seemed unwilling to turn back and fought several battles, most notably Cyropolis, Jaxartes and Gabai, before finally finding himself confronted by the Sogdian Rock, a hilltop fortress whose location has never been securely identified, but which was probably near Samarkand. When Alexander's heralds summoned the garrison to surrender, they proudly answered that Alexander would need soldiers with wings to gain access to their fortress.

Alexander was nothing if not innovative. At Tyre he ordered the old mainland city demolished and its remains thrown into the sea to contruct a causeway out to the island city (incidentally fulfilling the prediction of Ezekiel 26:12 which, in those days before bulldozers and dump trucks had seemed most improbable). At the Sogdian Rock Alexander studied the cliffs that surrounded it and concluded that it could be climbed. This was also a remarkable feat, for the ancients had a terror of rocks and cliffs.

There were 300 men in the army with experience of rock climbing who volunteered to attempt the impossible. Using wooden tent pegs and lightweight ropes of flax, they managed to climb the cliffs in the dark, only losing about thirty men in the ascent. When dawn broke they signalled their success by standing on the summit and waving linen sheets. Alexander promptly sent another herald to tell the defenders that he had found his winged men and when they looked up and saw the flapping linen, they promptly surrendered!

Among the captives were the wife and daughters of Oxyartes, a Persian satrap and one of Bessus' companions. One of the daughters, a girl called Roxana, seems to have met all the Greek qualifications for beauty; the Greek historian Arrian recored that she was "the loveliest woman they had seen in Asia, with the one exception of Darius' wife". Alexander took one look at her and fell desperately in love. Whether intended or not, it turned out to be an astute political move, for Oxyartes saw the advantages of being Alexander's father-in-law and promptly surrendered and was made governor of the province of Paropamisadae in eastern Afghanistan. He seems to have coped with the Pathans rather better than either the British or the Americans have managed.

| |

| This fresco from Pompeii is thought to represent the marriage of Alexander and Stateira. She is shown wearing a crown and holding a sceptre, but it may be doubted whether Alexander did indeed conduct his nuptials in the nude! |

Six years later Alexander finally found time to make Roxana pregnant, only to die shortly after from either malaria or drunkenness (or possibly both) in Babylon. As he lay dying, he was asked who should succeed him and he is supposed to have replied, "The strongest". Whether true or not, it is certainly a fact that his generals promptly started to try and carve out positions of power for themselves.

As in theory the crown should go to Alexander's son, not yet born, the generals decided to appoint one of their number, a man called Perdiccas, as regent. Meleager, commander of the infantry, felt that he had not been consulted properly and led a revolt which demanded that the throne should go to Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander the Great's half-brother (and, some claim, half-witted!) To appease the infantry, the bulk of the army, both sides agreed that the kingship should be joint between Philip Arrhidaeus and Roxana's child, if he was a boy. Not long afterwards, Perdiccas quietly arranged for Meleager to be murdered.

Seeing the sort of man he was, Roxana got in touch with him and arranged for her own rivals to be eliminated. Alexander had two other wives, Stateira, the daughter of the Persian king Darius, and Parysatis, Stateira's cousin. Both women were murdered and although there may have been political motives for this act, one cannot help but wonder whether the Persian princesses had snubbed Roxana, the daughter of a minor provincial governor, and this was her revenge!

| |

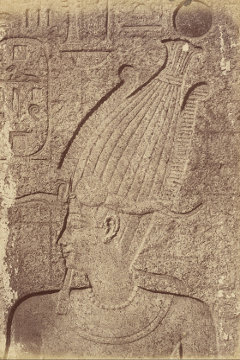

| This relief from Karnak is believed to depict Philip Arrhidaeus as a typical Egyptian pharaoh |

Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great, had a daughter called Cynane by the Illyrian princess Audata. Cynane was raised in the Illyrian tradition as a bit of a tomboy. She could ride, hunt and fight and is supposed to have led armies in battle, including one conflict against her own people in which she killed Caeria, the queen of Illyria, with her own hand. Seeing her half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, made king and being too old to marry him herself, she determined to have him marry her daughter, Eurydice.

Negotiations for the wedding took place and Philip Arrhidaeus agreed to the proposal. Cynane set out for Asia to bring her daughter to the wedding. Perdiccas saw the marriage as a threat to his own authority and promptly sent his brother Alcetas, to murder Cynane, which he had to do with his own hands because his troops refused to kill the half-sister of Alexander the Great. Somehow Eurydice managed to escape and made her way to Philip, who married her and settled down to a happy domestic life. He forgot that Eurydice had been raised in the same Illyrian tradition as her mother and had no intention of settling down to domestic anything!

Unfortunately Perdiccas was not liked by many people and when he attempted to enforce his authority on the other generals who were fighting each other, he was assassinated by his own officers in Egypt, where he was attacking Ptolemy, in 320 BC. That left the regency vacant and two other generals, Peithon and Arrhidaeus (not Philip!) were appointed in his place, but that did not suit Eurydice. By clever political manoeuvring she managed to get them both to resign. I imagine she was hoping that her husband would be allowed to rule as king without a regent, but instead the council of Triparadisus appointed Antipater as the new regent.

Antipater returned to Macedonia, taking Philip Arrhidaeus and a no doubt fuming Eurydice with him. A year later Antipater was dead of natural causes - he was an old man - but he bequeathed the regency, not to his son, Cassander, but to his friend and lieutenant, Polyperchon.

Meanwhile Roxana fled to Epirus, where she came under the protection of Alexander's mother, Olympias. Olympias was friends with Polyperchon, so when he became the new regent, Roxana must have thought that she was safe at last. Unfortunately Cassander was furious at being passed over and rallied troops to his cause. He was able to expel Polyperchon from Macedonia.

Eurydice saw her chance and quickly persuaded her husband to declare his support for Cassander as regent. Cassander reciprocated by appointing Eurydice as his representative while he pursued Polyperchon into Greece. This represented a threat to Roxana and her infant son, so she and Olympias recruited an army and together with Polyperchon they invaded Macedonia, where the Macedonian soldiers refused to fight against Alexander's mother. Poor Philip Arrhidaeus and his formidable wife were captured and imprisoned at Amphipolis.

Olympias had many enemies and Cassander was still engaging in hostilities against Polyperchon and his supporters in Greece. For these people Philip was a useful tool or rallying point and on Christmas Day, 317 BC, Olympias arranged for Philip Arrhidaeus to be murdered in his prison. Eurydice was forced to commit suicide, an act which must have given both Olympias and Roxana a certain grim satisfaction. In the same holocaust, Olympias murdered 100 of Cassander's supporters and his brother.

Cassander, meanwhile, allied himself with Ptolemy, Lysimachus and Antigonus and with their help he was able to defeat Polyperchon's fleet. He captured Athens and in this same year of 317 BC felt strong enough to declare himself regent. Polyperchon fled into the Peloponnesus and waited, with a sure knowledge that Greeks can never agree with each other for long. Sure enough, in 311 BC Antigonus broke with Ptolemy and Lysimachus and as a good will gesture, sent the 18-year old Heracles, supposed to be Alexander's illegitimate son, to Polyperchon, to be used as a bargaining chip against Cassander.

| |

| An artist's reconstruction of the tomb at Amphipolis with the Lion on the summit of the mound. |

What Antigonus didn't know was that Polyperchon was also negotiating with Cassander and eventually, in return for a substantial sum of money, he murdered Heracles in 309 BC. Polyperchon subsided into obscurity; the last secure mention of him is in 304 BC, but it is possible he lived on into the third century BC.

We return to Macedonia and Cassander. Having defeated Polyperchon, Cassander was free to turn against Olympias. He trapped her in Pydna, where he besieged her for two years and the city finally surrendered in 315 BC. One of the terms of the surrender was that the lives of Olympias, Roxana and her son should be spared, but Olympias had killed Cassander's brother and he was not about to forgive. He ordered his men to kill her and when they refused, out of reverence for the mother of Alexander, he simply withdrew her guards and let the relatives of those hundred murdered men know.

Olympias was stoned to death and Cassander left her body unburied, a pointed contrast with his behaviour towards Philip Arrhidaeus and Eurydice, for in early 316 BC he arranged a splendid funeral for them. We may feel sorry for Olympias, but never forget that when her husband, Philip, died, she had the young woman who had succeeded her in his affections, and her baby daughter, burned alive! Roxana and her son, Alexander IV, were sent to Amphipolis and imprisoned there.

Cassander was an interesting character whose motivations are not completely understood. He was so much in awe of Alexander the Great that it was said that he could not even pass a statue of Alexander without feeling faint, yet at the same time he was responsible for murdering Alexander's mother, his wife and his son. In addition, he restored the city of Thebes, which had been destroyed by Alexander, an action which was widely regarded as a snub to the memory of Alexander the Great.

It is no surprise, therefore, that in 310 BC Cassander murdered both Roxana and her son. Unlike Olympias, however, Cassander permitted the pair to be buried, though no details survive of the obsequies.

| |

| A general view of the burial mound at Amphipolis. Notce the size of the car in front of the tomb entrance. |

It cannot have escape your notice, I trust, that I have mentioned Amphipolis several times. Philip Arrhideus and his wife Eurydice were killed there by Olympias and Roxana and, a few months later, buried there by Cassander. Roxana and her son were imprisoned there and later murdered and buried there.

It also, I am sure, has been brought to your attention that Greek archaeologists have recently excavated a huge tumulus at Amphipolis and speculation has been rife about who might be buried there. The style of the tomb and the carvings and mosaic found inside it point to the time of Alexander the Great, but there is no inscription to indicate the occupant - or intended occupant - of the mound.

Dorothy King, an American archaeologist, claims that the mound was intended as a cenotaph for Alexander the Great, while others suggest that the tomb was intended to actually be Alexander's burial place. Another favoured theory is that it was - or was intended to be - the tomb of Olympias, Alexander's mother. Other experts have suggested that it is the tomb of Alexander's wife, Roxana. Yet others claim that the mound was the burial place of some important official of the time of Alexander and some have named him as Laomedon.

Laomedon was one of Alexander's trusted confidantes, but though he accompanied the king to Persia, he played no great part in the fighting. Instead, because he knew the Persian language, he was put in charge of the Persian captives - by which, I presume, the royal family rather than the thousands of common soldiers. When Alexander died he was appointed as governor of Syria, but was ousted by Ptolemy. It is claimed that after he escaped from imprisonment in Egypt he was offered the city of Amphipolis, but no one knows whether he actually ruled there or what eventually happened to him.

I think we can dismiss most of these contenders.

| |

| The floor of the second room in the tomb was a mosaic depicting the abduction of Persephone. A large hole was broken in the centre of the mosaic in antiquity. |

Alexander had no reason to be buried in Amphipolis, a city which was captured by his father but never incorporated into Macedonia. At most it was an important naval base and the birthplace of three Macedonian admirals. If he wanted to be buried anywhere in Greece, it would have been at Vergina, the place where his own father was buried.

Olympias was not killed at Amphipolis but at Pydna, and far from giving her a spectacular burial in the largest burial mount in Greece - the mound is 1,935' in diameter - Cassander gave her no burial at all. Nor is there any reason why she would have planned to be buried in the obscure former Athenian colony; if she made any plans for her tomb she would have chosen to be buried either in her homeland of Epirus or in Vergina.

Roxana and her son were killed in Amphipolis, but it is unlikely that Cassander went to great trouble to bury her and, in fact, one of the tombs discovered at Vergina has been identified as the tomb of her son, Alexander IV, so the likelihood must be that she was buried near her son.

Laomedon or some other Macedonian official may have had delusions of grandeur, but whether he would have had the influence and the resources to build the largest burial mound in Greece may be doubted. It is true that the so-called Lion of Amphipolis (which my group on the Diggings tour of Greece photographed) has been identified as coming from the tomb of Laomedon, but that is merely guesswork, for there is no inscription to support that identification.

To my mind there is only one possible candidate for this spectacular tomb and that is Philip Arrhidaeus and his wife Eurydice. They were killed in Amphipolis; they were buried there by Cassander who may well have built this ostentatiously large monument as a statement of his respect for them - the burial place of a king erected by a king.

Alexander's innocence It is interesting to speculate on what Alexander would have done with Darius had he succeeded in capturing him. We know that Alexander treated the captured Persian royal women with honour, but that might be explained as a prudent political move. It is hard to see what advantage he might have gained from allowing Darius to live, but it is not impossible that Alexander had some plan to make Darius his vassal. After all, Cyrus reportedly did the same with Croesus, making his former enemy governor of a remote part of his empire! Return

© Kendall K. Down 2014