Mary Jones and the very old Bible

There has been a certain amount of amusement recently over an advertisement by Swedish furniture manufacturer Ikea, which begins with the commentator declaring that sometimes an invention comes along that you instinctively feel is going to change the world - and here is one such invention, the "bookbook". If you haven't seen it, it is worth watching. www.youtube.com/watch?v=MOXQo7nURs0

Certainly the initial statement is correct, because the original "bookbooks" certainly changed the world - but there were two things necessary to the book revolution. The first, obviously, was Gutenberg's invention of printing using moveable type or, more precisely, reusable type. It is amusing to realise that one of the ethical issues raised by printing was the question of whether it was right to use the little lead letters that might have been used for printing a secular book in the holy work of printing a Bible or a religious text!

What we often forget, however, is that Gutenberg's inventiveness would have gone to waste if he had not had something on which to print - paper! In the early 1300s paper was being produced in Spain and other countries along the Mediterranean coast, but it wasn't until the early 1400s that paper-making became more widespread and Gutenberg, of course, made his breakthrough around 1439.

Before then books were made of parchment or vellum - vellum is prepared calf-skin whereas parchment can be the skin of any animal, including goats, sheep or even donkeys. The process of preparing the animal skin was long and slow, for the skin had to be soaked in beer for a week to remove the hair, then dried under tension and scraped with a special semi-circular knife to remove unwanted tissue and thin the leather down to the required thickness. Finally the skin would be rubbed with pumice and coated with lime and egg-white to make a surface that would take the ink.

Ironically, parchment takes its name from the ancient city of Pergamon (and is known in many European languages as "pergamum" or "pergamos"). When Eumenes II tried to set up a large library in his city, the inhabitants of Alexandria, which boasted the largest library of the ancient world, felt threatened. In an attempt to stifle a potential rivel, the librarians persuaded Ptolemy V to ban the export of papyrus, the most common writing material of the ancient world. Eumenes set his scientists to work and they came up with parchment as a substitute for papyrus.

The amount of leather in an ancient book was incredible. The Lindisfarne Gospels, for example, are made of the skins of 130 calves while the largest mediaeval book, the Codex Gigas (otherwise known as "the Devil's Bible"), is made of the skins of 160 donkeys. This enormous book is 36" tall - that is, a yard! - and 19.7" wide and weighs 165 lbs. It takes two men to lift it - not exactly the sort of book you would want for reading in bed!

One result of this was that mediaeval scribes had a solid financial incentive to reuse their parchments. Not only might strips from the margins of books be cut off to be used as notepaper, but entire pages could be erased and rewritten. Erasing, however, was hard work. Modern erasers or rubbers are made from vegetable oil, sulphur and 20% rubber and are very effective at removing graphite from paper. They are less successful at removing ink, for ink soaks into the fibres of the paper.

Mediaeval scribes faced the same problem - ink soaks into the fibres of the parchment and the only way to remove it is to remove those fibres, which was done for individual letters by scraping with a sharp knife. If you had a whole page to erase, however, the only practical solution was a piece of pumice. Needless to say, if you were too enthusiastic with your pumice you could end up erasing the parchment altogether and rub holes in your surface! Both to avoid this disaster, which would make the whole page unusable, and from laziness, scribes often were less than thorough in their erasing and it was possible to make out the previous writing underneath the new text. Such a half-erased document became known as a "palimpsest".

The task of reading the underlying and half-erased text can often be a difficult one. Codex Vaticanus 2061, for example, has been overwritten twice. The oldest text dates from the 5th century AD while the youngest is from the 10th century. The Codex Ephraemi, in Paris, has a 5th century text overwritten by a document from the 12th century.

| |

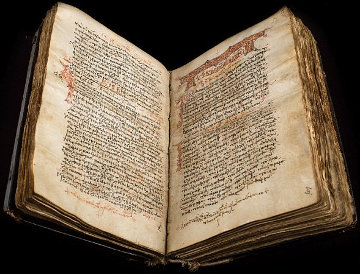

| The Codex Zacynthius has 176 leaves of vellum and in the 16th century was given a goatskin binding. |

The Bible Society - formerly known as the British and Foreign Bible Society - holds a remarkable collection of old Bibles, among them the Bible purchased by Mary Jones, the Welsh girl whose longing for a Bible of her own led to the formation of the BFBS. However not only are the earliest Bibles very valuable, but the task of conserving them is expensive and the Bible Society - rightly or wrongly - feels that the money contributed to it can be used for better purposes. As a result the Society recently decided to sell one of its ancient Bibles, a book it has held for two centuries.

The Codex Zacynthius was found in a monastery on the Greek island of Zakynthos or Zante. It has 176 pages (or leaves) made of vellum and was first written in the 6th century with a copy of the gospel of Luke (of which only chapter 1:1 to 11:33 survive). However in the 13th century the tospel was erased and overwritten with an Evangeliarium, a sort of compilation from all four gospels in which the different viewpoints of the four authors are combined and rearranged to make one consecutive narrative.

| |

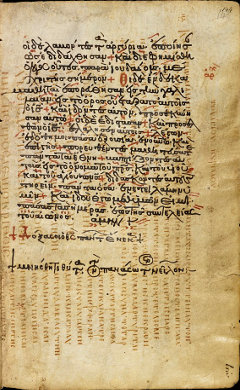

| A page from the Codex Zacynthius. The black text is from the Evangeliarium, the red from the gospel of Luke. |

The original text was first read in 1861, but scholars believe that there are numerous errors in the reading - almost inevitable when you are trying to read writing that is obscured by other writing - and Cambridge University, which raised the £1.1 million price for the Codex has loudly trumpeted its intention to use modern photographic techniques to discover the underlying text and produce a more accurate reading. I suspect, however, that this intention, laudable though it is, is nothing more than a gimmick to aid in the fund-raising, for the University Library has held the Codex since 1984 and could, at any time since them, have conducted this study.

The hope is that the old manuscript of Luke will give us insights into the way the gospel has come down to us and perhaps clarify or correct some of the variant readings that have puzzled scholars. It is not only the text of the gospel that will do this, but there is also a commentary written beside the text which will show how the 6th century authors understood the text.

I must admit that I am less sanguine. Although the commentary will certainly show us how the 6th century interpreted the text, that is not a reliable guide to what Luke intended by what he wrote! Some of those old monks had highly developed imaginations and the anagogical method of interpretation gave them wide range for indulging those imaginations. Any conclusions reached about the "true" meaning of the text are likely to be highly unreliable! Given that Origen is among the authorities quoted in this commentary, I am even less confident.

Unfortunately, according to Wikipedia, the Bible Society intends to use the money raised by the sale of this important Codex, not for the laudable aim of translating the Bible into new languages, but to build a visitor centre in Wales. I strongly suspect that this is the unfortunately named "Mary Jones World" due to open on October 5 at Llanycil. Mary Jones World, forsooth! What attractions will it offer the discerning visitor? The world scariest Bible-based roller-coaster? The Witch of Endor Haunted House?

I fear not. The centre is based in a redundant chapel and will be little more than the size of an ordinary house (or small town house if you live in America or Australia). I strongly suspect that it will contain little more than a few information panels and perhaps a computer display or two. Although I am all in favour of making the story of Mary Jones better known, I wonder whether the Bible Society is getting value for money by exchanging a priceless codex for a run-down chapel and a couple of LCD screens.

a piece of pumice You may wonder why the scribes didn't simply wash the ink off the piece of leather. The answer is that parchment is not tanned, merely dried, and is very susceptible to humidity and damp. Deluging a piece of parchment with water runs the very real risk that you will end up with a lump of glue! In any case, not all the inks used by mediaeval scribes were water-soluble once they had dried and one method of washing was to use a mixture of milk and bran! Return

© Kendall K. Down 2014