Gilgamesh Restored

| Slemani | 35 33 42.93N 45 25 22.14E | Otherwise known as Sulaymaniyah, the town appears to be a thriving modern town amid the chaos of Iraq. |

| Uruk | 31 19 26.46N 45 38 21.64E | There is virtually nothing to distinguish the once famous city from the surrounding desert, though from the ground there is a distinct tel burying the famous walls. |

If you say "Epic of Gilgamesh" to most people, you will probably get a puzzled, "What?" in response. Most of those few who do know what you are talking about will nod and say, "Ah yes, the flood story". In fact the story that is so similar to the Bible's tale of Noah's Flood is only a small part of a much longer poem that, for long life, must rank as the world's greatest work of literature.

The epic was first read and recognised by George Smith, a young apprentice printer who abandoned his apprenticeship to work at the British Museum after he taught himself to read cuneiform. One of his tasks was to organise and translate the huge number of cuneiform tablets sent back to the Museum by Layard and Hormuzd Rassam from Mosul.

Translating cuneiform tablets is a fairly disheartening task, as the vast majority of them are simply commercial records and about as interesting as a till receipt. After the two hundred and thirty-seventh tablet recording that in the x year, x month and x day of king x, two sheep and a bushel of barley was paid to the royal tax collectors, the task of painting the Forth Bridge suddenly becomes very attractive! George cannot be blamed, therefore, for his pleasure in translating what turned out to be a long and complex poem telling the adventures of Gilgamesh, king of Uruk.

Pleasure turned to excitement when Smith came to the eleventh tablet and began to read the account of Utnapishtim's flood, which was in many ways almost identical to the Biblical story. It is likely that in these days of ignorance someone could translate the tale without recognising its Biblical connections, but in those days, a mere 28 years after Darwin's theory was formed, the Bible was still a cornerstone of British life and everyone was familiar with its stories.

News of what Smith had discovered leaked out and when he presented a paper to the Society for Biblical Archaeology, the hall was packed. Among those present was Prime Minister Gladstone, the only recorded instance of a British prime minister taking an interest in Biblical Archaeology!

I have recently been examining the Mythological and Mythical tablets, and from this section I obtained a number of tablets, giving a curious series of legends and including a copy of the story of the Flood.

On discovering these documents, which were much mutilated, I searched over all the collections of fragments of inscriptions, consisting of several thousands of smaller pieces, and ultimately recovered 80 fragments of these legends; by the aid of which I was enabled to restore nearly all the text of the description of the Flood, and considerable portions of the other legends. These tablets were originally at least twelve in number, forming one story or set of legends, the account of the Flood being on the eleventh tablet.

George Smith, December 3, 1872

In view of the fact that people have since used the Epic of Gilgamesh to try and discredit the Bible story, claiming that Bible authors copied from the Babylonian myth, it is interesting to read Smith's own conclusion.

On reviewing the evidence it is apparent that the events of the Flood narrated in the Bible and the inscription are the same, and occur in the same order; but the minor differences in the details show that the inscription embodies a distinct and independent tradition.

In spite of a striking similarity in style, which shows itself in several places, the two narratives belong to totally distinct peoples. The Biblical account is the version of an inland people, the name of the ark in Genesis means a chest or box, and not a ship; there is no notice of the sea or of launching, no pilots are spoken of, no navigation is mentioned.

The inscription on the other hand belongs to a maritime people, the ark is called a ship, the ship is launched into the sea, trial is made of it, and it is given in charge of a pilot.

George Smith, December 3, 1872

Since then other versions of the Epic have been discovered, dating all the way back to Sumerian times, and it is possible to trace the evolution of the story of Gilgamesh. Scholars believe that the famous Epic started out as a series of separate stories, but as they all centred on the same figure - the semi-mythical king of Uruk - they were eventually combined into one continuous narrative. As Wallis Budge, Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum, stated in his little pamphlet:

It now seems that the Legend of the Flood had not originally any connection with the Legend of Gilgamish, and that it was introduced into it by a late editor or redactor of the Legend, probably in order to complete the number of the Twelve Tablets on which it was written in the time of Ashur-bani-pal.

Wallis Budge The Babylonian Story of the Deluge and the Epic of Gilgamish 1829

In what has become known as the "standard version", the Epic goes like this:

Tablet 1

Gilgamesh oppresses his people by raping young women on their wedding night and forcing the young men to work on his building projects, including the massive walls of Uruk. The people call on the gods for help and they respond by sending Enkidu, a wild man. Gilgamesh, realising that he could not defeat the man in a trial by strength, cleverly sends a temple prostitute to seduce him and after a week of love-making poor Enkidu is so weak that he allows himself to be led to a camp of shepherds, where he can learn about civilisation.

Tablet 2

Enkidu starts to eat human food. When he hears about how Gilgamesh treats new brides, he determines to stop him and there is a fight between Gilgamesh and Enkidu in the doorway of a bridal chamber. Due to his human diet and his love-making, Enkidu is, in fact, beaten by Gilgamesh - the gods don't always get it right! - but the two become friends and Gilgamesh proposes that they travel to the Cedar Forest to slay its guardian.

Tablet 3

Gilgamesh prepares for his journey and his mother, who is herself a goddess, obtains the protection of the sun-god Shamash for her son.

Tablet 4

Gilgamesh and Enkidu travel to the Cedar Forest, but along the way Gilgamesh is terrified by a succession of dreams, which Enkidu interprets for him in an encouraging way.

Tablet 5

Gilgamesh and Enkidu enter the forest and fight with its guardian monster, Humbaba. With the help of Shamash, Gilgamesh is victorious, but chivalrously wishes to spare Humbaba's life. Enkidu, who sees that the monster will not be tamed, rejects mercy and Humbaba is killed, leaving the two free to chop down cedar trees for use in Uruk.

Tablet 6

Back in Uruk Gilgamesh is so far reformed that he rejects the goddess Ishtar who attempts to seduce him. Hell hath no fury like a goddess scorned and Ishtar sends the Bull of Heaven to devastate the lands around Uruk. Gilgamesh and Enkidu together kill the Bull and Enkidu hurls its hindquarters at the outraged goddess. While the city celebrates its deliverance Enkidu dreams of his coming death.

Tablet 7

A council of the gods decides that one of the two heroes must die for daring to kill the Bull of Heaven and the lot falls on Enkidu. Enkidu rages against his fate but is finally reconciled to it by the promise of a splendid funeral. After twelve days of sickness Enkidu dies.

Tablet 8

Gilgamesh laments over his dead friend and prepares a magnificent funeral, including rich grave goods to ensure Enkidu a good reception in the Underworld.

Tablet 9

In his grief Gilgamesh leaves Uruk and wanders in the wild. Realising that one day he, too, will die, he decides to visit Utnapishtim, the man who alone is immortal. After various adventures he reaches the the Garden of the Gods.

Tablet 10

Gilgamesh meets a woman who directs him to Urshanabi, the ferryman who can take him to Utnapishtim. Unfortunately Gilgamesh destroys the Stone Giants, only to discover that they are the only creatures who can cross the Waters of Death unaffected. However Urshanabi eventually takes him to the island (Dilmun?) where Utnapishtim lives, but Utnapishtim tells him that it is impossible to fight against man's fate.

Tablet 11

Gilgamesh asks how Utnapishtim came to be immortal and is told the story of the Flood, as a result of which Utnapishtim and his wife were granted immortality. To prove that man cannot be immortal, Utnapishtim challenges Gilgamesh to stay awake for a week, but of course Gilgamesh fails. However Utnapishtim does tell him of a plant at the bottom of the sea that can renew youth. Gilgamesh manages to find it, but on his way home it is stolen by a snake, which promptly sheds its old skin. Gilgamesh, realising his quest is hopeless, returns to Uruk, whose massive walls make him realise that he has achieved the immortality of fame.

Tablet 12

Gilgamesh meets Enkidu and offers him advice on what not to do in the Underworld if he is to have a hope of returning. Enkidu enters the Underworld and promptly does everything he was told not to do. Gilgamesh appeals to the gods for help and Ea and Shamash make a crack in the earth out of which Enkidu's ghost emerges. Gilgamesh questions him about what he has seen in the Underworld.

In the Sumerian version of the epic there are several omissions and variations. The first tablet is in essence the Cedar Forest story, the second tablet is the Bull of Heaven. Tablet three recounts a battle between Uruk and Kish in which Gilgamesh emerges victorious and offers mercy to his defeated foe. Tablet four tells of Enkidu's journey to the Underworld. Tablet five describes the death and burial of Gilgamesh, here called Bilgames.

There is no corresponding flood story in the Sumerian version, but as noted above, the flood story was probably a separate tale woven into the Gilgamesh story by the later author, rather like a modern novelist might incorporate elements from Robin Hood into a story set in the time of Richard the Lionheart.

| |

| The remains of a monumental building and the ruins of Uruk lie deserted on the desert. |

For a long time the Epic was regarded as a work of fiction, pure and simple, but recent archaeological discoveries hint at the possibility of a historical background to the story. For example, the Tummal Inscription lists the names of kings who built temples in Nippur and Tummal and among those listed is Enmebaragesi, father of Aga, both of whom are mentioned in the Epic as enemies of Gilgamesh. The Sumerian King List names Gilgamesh as king of Uruk and gives him a reign of 126 years, an unlikely but not entirely impossible figure.

In 2003 German archaeologists in Iraq surveyed the site of Uruk using modern technology. Jorg Fassbinder, of the Bavarian Department of Historical Monuments in Munich reported their discoveries.

"By differences in magnetisation in the soil, you can look into the ground. The difference between mudbricks and sediments gives a very detailed structure. The most surprising thing was that we found structures already described by Gilgamesh. We covered more than 100 hectares. We have found garden structures and field structures as described in the Epic, and we found Babylonian houses."

BBC Interview

According to the Sumerian Epic, when Gilgamesh died the River Euphrates was temporarily diverted from its channel and the king was buried in the river bed, after which the river was returned to its course. The German team identified a structure in the now dry bed of the river which they claimed may have been the tomb of Gilgamesh. Unfortunately the wars in Iraq have prevented any further exploration of the site.

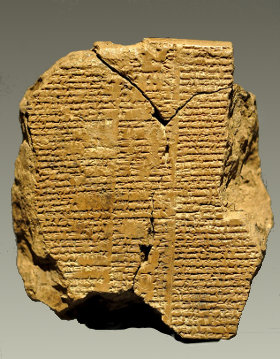

All the surviving tablets of the Gilgamesh Epic are broken or damaged in some way. Fortunately there are numerous versions of the epic and for the most part it has proved possible to reconstruct the missing lines by reference to another tablet. Despite this there are still gaps, but one of these has recently been filled.

| |

| The newly discovered tablet corresponding to Tablet 5 of the Epic of Gilgamesh. |

The Suleymaniyeh Museum in Slemani, in Iraqi Kurdistan, has been bucking the trend and dealing with antiquities smugglers with the intention of recovering some of the objects looted since the breakdown of law and order in that country - most museums refuse to have such dealings on the grounds that they would encourage looting.

"The tablet presented here is the left half of a six-column tablet inscribed in a fine and delicate Neo-Babylonian hand with a copy of Tablet V of the Standard Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh. It was acquired by Suleimaniyah Museum in the jurisdiction of the Kurdish Regional Government in 2011 with other Babylonian antiquities of the kind found in southern Iraq; its exact provenance is therefore unknown. The script and circumstances of acquisition make it highly probable that it was unearthed at a Babylonian site. The tablet measures 11.0×9.5×3.0 cm, and now bears the Suleimaniyah Museum number T.1447."

Farouk al-Rawi Back to the Cedar Forest

On translation and study it appears that the tablet, which cost the museum $800, contains twenty lines from a poem about Gilgamesh and Enkidu and which may be part of the missing introduction to Tablet 5. It not only reveals that Enkidu and Humbaba were childhood friends - which explains why Humbaba accuses Enkidu of betraying him - but it also describes the forest itself, which was alive with bird-song and the sound of monkeys screaming in the trees.

"The passage gives a context for the simile 'like musicians' that occurs in a very broken context in the Hittite version's description of Gilgamesh and Enkidu's arrival at the Cedar Forest. Humbaba emerges not as a barbarian ogre and but as a foreign ruler entertained with music at court in the manner of Babylonian kings, but music of a more exotic kind, played by a band of equally exotic musicians."

Farouk al-Rawi, Back to the Cedar Forest

(You can find the full text of Dr al-Rawi's report on the American Schools of Oriental Research website.)

apprentice printer He was actually learning to engrave bank notes at the publishing house of Bradbury and Evans. Return

huge number Counts vary, but Wikipedia gives the figure of 30,943, which is curiously precise given that many of the tablets are broken and as the pieces are identified and united the number of actual tablets will certainly decrease. Return

discredit the Bible story This tendency manifested itself almost as soon as George Smith announced his discovery. The New York Times report declared:

This discovery is evidently destined to excite a lively controversy. For the present the orthodox people are in great delight, and are very much prepossessed by the corroboration which it affords to Biblical history. It is possible, however, as has been pointed out, that the Chaldean inscription, if genuine, may be regarded as a confirmation of the statement that there are various traditions of the deluge apart from the Biblical one, which is perhaps legendary like the rest.

New York Times December 22, 1872

On the other hand, Wallis Budge, director of the British Museum, stated the conclusion that seems to be warranted by the facts - the differences reported by George Smith.

It is probable that both the Sumerians and the Semites [the Jews - KKD.], each in their own way, attempted to commemorate an appalling disaster of unparalleled magnitude, the knowledge of which, through tradition, was common to both peoples. It is, at all events, well-known that the Sumerians regarded the Deluge as an historic event which they were able to date, for some of their records contain lists of kings who reigned before the Deluge - though it must be confessed that the lengths assigned to their reigns are incredible. After their rule it is expressly noted that the Flood occurred and that, when it passed away, "kingship came down again from on high".

Wallis Budge The Babylonian Story of the Deluge and the Epic of Gilgamish 1829

© Kendall K. Down 2015