Vandals in Palmyra

| Temple of Bel | 34 32 50.58N 38 16 26.74E | The magnificent temple of Bel is one of the main sights of Palmyra. |

| Theatre | 34 33 02.46N 38 16 07.57E | The splendidly preserved theatre of Palmyra. |

| Tower Tombs | 34 33 12.71N 38 15 01.33E | It is hard to see the tower tombs in this view from above, but there is no mistaking the long shadows they cast. |

| The Spring | 34 32 54.00N 38 15 31.78E | The never-failing spring which made Tadmor what it is, but which has run dry thanks to over-extraction. |

It must be getting on for twenty years ago now that I made my first and only trip to Palmyra. I was working with my father to record a film which was released as Solomon's Kingdom (and is still available from the Digging Up the Past website) and we toured Syria, visiting all the places mentioned as being part of the kingdom ruled by King Solomon at the height of his power.

Our first problem was to hire a car. In contrast with Beirut, just a few miles away on the sea coast, where every second shop seems to be a car hire place, there were only two car hire establishments in Damascus and both charged ridiculous prices. What is more, neither seemed very keen on hiring cars!

The problem, it turned out, was the traffic. Syrians, in common with most Arabs, bitterly resent law and order. The stern hand of Bashir al-Assad enforced compliance in certain matters, but either he couldn't be bothered to concern himself with traffic rules or, perhaps more likely, he recognised the impossible and wisely kept out of it. The result is that although Damascus has all the apurtenances of civilised life - traffic lights and one-way streets and so on - they are there simply for show. At most a red light will produce a minor slowing of traffic, a minute hesitation in the stream of rushing cars.

To visitors from the West, the chaos can be daunting and they return, hair standing on end, to hand back the keys of a brand new but badly battered car, dented in the rear when they adopted the unexpected manoeuvre of stopping at a red light and smashed in from the sides when they drove blithely through a green light. Having driven in Teheran - which sets a standard in bad driving that even Arabs can only aim at - and Beirut itself, where a two lane highway will commonly have three lanes of weaving traffic, I assured the proprietor that I thought I could manage and, somewhat reluctantly, he handed over the keys for the car. The air of pessimism as he conducted the pre-rental checks was almost comic in its intensity.

Early the following morning my father and I set out and I must admit that once or twice, in the next three quarters of an hour, I almost regretted my foolish daring. Fortunately my fool-proof method for driving in such situations got us through and after 45 minutes of the hairiest driving I have ever done, we reached the outskirts of the city and the traffic disappeared!

The road north was a perfectly decent tar-sealed road and we met a car every ten minutes or so, but that was about it. Whether the people of Syria are too poor to own cars or the restrictions on travel are so draconian that no one travels, I could not say, but the fact is that we did not meet heavy traffic again until we reached Aleppo!

We drove north to Hamath and Homs and filmed in both places, conscious that the nice new blocks of flats replaced those that had been shelled to pieces by the previous president when the locals rose in revolt. We had no problems and the people we met were perfectly friendly. We headed across the top end of the Rift Valley to Latakia and Ugarit, then drove back east again to Aleppo. From there we drove south across fertile plains to Ebla and the museum at Idlib and then we turned east and followed signposts to Palmyra.

| |

| The road to Palmyra leads through a featureless wilderness. |

The ground was as flat as a table-top and instead of the sandy desert I had been unconsciouly expecting, the ground was covered with a low growth of grey bushes. The land sloped slightly but steadily downhill, and every half a mile or so we encountered a couple of army tents and a tank, buried up to its turret and surrounded by earthworks. It was noticeable that every one of the tanks was facing east towards Iraq, for in those days Syria and Saddam Husein were not the best of friends.

Gradually the bushes became more sparse and patches of actual desert more frequent and finally, late in the day, we came in sight of the distinctive old fortress that overlooks Palmyra and then we recognised the first of the tower tombs - and at that point there was a barrier of sand-filled 44-gallon drums across the highway and the road beyond had been pretty comprehensively dug up. Someone was serious about not letting people drive past the tombs! Instead we had to turn left and take a wide detour which brought us into Tadmor from the north.

I must admit I was pretty peeved about it. The entrance into Palmyra past the tower tombs of its nobility was one of the features of the place and I had been looking forward to retracing the steps of all the travellers whose descriptions of Palmyra I had read. Going back out to the tombs, as we did in the morning, just wasn't the same.

| |

| A non-vegetarian dish of mansaf. |

Still, there was nothing we could do about it. The modern town, a grubby Arab village with narrow, crowded streets lay ahead. It seemed that every house and hovel in the place had been transformed into a hotel, indicating that tourism was booming. We found a relatively quiet hotel which did not advertise a "luxury swimming pool" or "Nite Club!!!" and were ushered into a comfortable and clean room. Even better, when we informed the man behind the desk that we were vegetarians, he didn't even bat an eyelid, but recommended the vegetarian mansaf, a house speciality, apparently.

Prepare a quantity of boiled rice (long grain for preference) and then take pieces of lamb and cook them in a sauce of fermented dried yoghut (jameed). When tender, take a mansaf, a large metal tray, and lay down a ground floor of pieces of Arab bread. On top of that dump your rice, and finally ladle the lamb and its sauce over the rice. Eat with the right hand only.

The vegetarian variation - which I am sure would not be recognised by any Arab housewife - had the bread and the rice and a sauce of buttermilk, but instead of the lamb there was a thick coating of pistachio nuts and a topping of fried onion. Delicious!

In the morning we discovered the reason why a small hotel-keeper in Palmyra knew all about vegetarian cooking: the place was swarming with tourists, most of whom had spent the night in the various hotels. A substantial colony of large campervans with German number plates and serious air-conditioning units mounted on their roofs, were laagered on the outskirts of the town. Yet such is the size of the ancient city that it did not feel at all crowded and only occasionally did we have to suspend filming as a tour group and guide wandered into shot.

| |

| A fairly intact tower tomb and the remains of another, with the Turkish fort in the background. |

Our first visit was to the tower tombs, tall, narrow towers of stone with up to four floors of loculi inside them. The tombs could hold several hundred burials - the Tower of Elebal, for example, had room for 260 bodies and it is likely that as well as the eponymous Elebal, the tower also held the bodies of his family and his servants. None of the towers were open at that time of the morning, but we could look in through the locked bars and see how, opposite the doorway, the owner of the tomb had depicted himself and his wife, reclining on a couch and obviously enjoying his funerary feast.

In other tombs the carving had been removed to the museum in Damascus and all that was left was a row or two of busts, niches and pilasters on the walls and a splendid coffered ceiling overhead. Unfortunately, of the more than sixty towers which once lined this road, the majority have been reduced by time and weather - and possibly the hand of man - to a few shattered walls or even a mound of fallen stone.

| |

| Palmyra's splendidly preserved theatre has been used for shows and events to attract tourists. |

From there we drove the short distance back to the centre of the ancient town and walked across the sand to the theatre, one of the best preserved in the Middle East. In recent years the theatre has staged dramatic productions and shows in an attempt to lure more tourists to the city. When we were there, however, the theatre was empty and silent apart from the occasional crowd of bored-looking tourists trudging through the hot sand while being harangued by their guide.

Just in front of the theatre is a very ruinous wall, which was erected in haste by the last independent ruler of Palmyra, Queen Zenobia. Trapped in her city by the Romans under Diocletian, she didn't have enough men to man the full circuit of the walls, so she boldly cut the city in half by this make-shift wall and thereby reduced the length of wall she had to defend.

| |

| The main street of Palmyra, over half a mile long, was lined on each side with a colonnade of pillars. |

On our way back to the car we walked most of the way along the main street of Palmyra, which has a splendid colonnade of pillars. Originally they no doubt supported a roof of sorts so that pedestrians could walk in the shade on either side while window shopping in the businesses that lined the street. Most of the pillas had brackets protruding at more than head-height. These probably once held statues of pominent people, but opinion is divided on whether the statues were never erected or were erected but since destroyed.

Of course, all these remains date to well after the time of Solomon, which is one reason why we didn't go into the Temple of Bel and merely used it as a backdrop to some of the shots. Even the famous Lion of al-Lat is no more than 2,000 years old, a thousand years after King Solomon.

| |

| The Lion of al-Lat, believed to represent a lion goddess once worshipped in the temple of Bel. |

Of greater interest to us was the ancient, never-failing spring of Ain Efqa, the reason for Palmyra's existence. Set in a desert region, the spring proved a convenient stopping point for camel caravans heading from Syria to Mesopotamia and the city grew up around it. The trouble was that no one seemed to know what we were talking about.

Fortunately I had done my homework and I knew what the spring looked like. In the tourist office I had noticed an aerial photograph of Palmyra, so we went back there and I studied it carefully - and finally located the spring, a distinctive triangular shape, rather further south of the city than we had expected. Now that we knew where it was, we had no difficulty in driving to it and there, sure enough, was the triangular wall around the spring. We climbed out, unloaded the camera gear, and while I set it all up my father strolled across to look down into the spring.

| |

| The dried up spring of Ain Efqa, thanks to over-extraction to keep the tourists happy. |

"Hey!" he called. "It's dry!"

I was so astonished that I actually left my camera - normally I am never more than arm's length from it - and rushed over to see for myself. Sure enough, the hole in the ground was as dry as the surrounding desert. Having come this far we filmed the spring and my father said his piece to camera, and then we went back to the tourist office. Now that we actually knew their deep, dark secret, the two men there were willing to talk. Apparently the spring had dried up a couple of years previously (in 1994, to be precise) because the water table in the ground was dropping all the time. All those luxury swimming pools - to say nothing of tourists who wanted lengthy showers every day - were draining the water from Palmyra's acquifers faster than it could be replenished. The officials hinted the the time might be not too far off when the water would be too deep down to be pumped and Tadmor would die.

With all our shots "in the can", we thankfully returned to the car, turned the air-conditioning to maximum and headed straight for Damascus. This time the route was as sandy and rocky as anyone could wish and made you wonder who the wandering genuis was who first found the spring and recognised its potential.

In early May, 2015, Palmyra was captured by the fanatical forces of ISIS or Daesh. They gained local support by promising not to destroy the ruins, for the locals were well aware of the importance of the remains in attracting wealthy tourists. Once they were in control, the barbarians promptly rounded up all the prominent locals - men, women and children - and either murdered them outright in the streets or, in a macabre piece of theatre, marched twenty men to the ancient theatre and shot them in front of a forcibly assembled mob of townspeople.

With the town thus cowed, the vandals started to destroy the ancient city. The Lion of al-Lat was one of the first to go, blown apart with explosives and the pieces crushed by industrial machinery so that it could never be restored. Although the invaders claim to be restricting destruction to "idols", it is doubtful whether they have the intelligence to differentiate between a genuine idol - something that was once worshipped - and any statue. I gravely fear that the busts and reliefs in the tower tombs will also be destroyed. We can be grateful that the best ones have been removed to the museum in Damascus - but if Damascus should fall, the loss to the world will be incalculable.

Not only will the original artefacts be destroyed, but the idiot Syrians strictly forbade any photography inside their museums, so there isn't even a photographic record of the treasures they hold.

Since writing the above there have been two developments. ISIS thugs have blown up the two best tower tombs, claiming that the busts of those buried within were "idols" and therefore contrary to Islam. A few days later two local men were stopped at a checkpoint and found to have a couple of the busts which had survived the explosion in the boot of their car. It is not clear whether the men were patriots attempting to smuggle the busts to safety or greedy chancers who wanted to turn a quick dollar out of the city's misfortune. Whatever their motives, they were forced at gun point to smash the busts with a sledgehammer before being flogged. They were lucky to escape with their lives!

| |

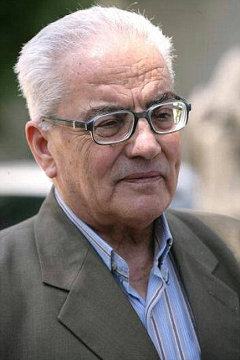

| Khaled Asaad, the former Head of Antiquities in Palmyra, who was brutally murdered by ISIS in August, 2015 |

The second piece of news is that Mr Khaled Asaad, a native of Tadmor who made the preservation of the city his life's work, was seized by ISIS thugs and tortured for a month to force him to reveal where the city's stores of gold were hidden. It is a staple of primitive Arab stupidity that all ancient ruins conceal vast quantities of gold and that Western interest in such ruins is a deeply disguised (but successful) search for the precious metal.

Mr Asaad was an expert in the history and culture of ancient Palmyra. He could read the Palmyrene script and language as easily as he could read his native Arabic. Although he retired thirteen years ago after fifty years as Head of Antiquities in Palmyra, ISIS thugs seized him and demanded that he reveal the hiding place of the gold. When he was unable to do so - there being no such gold - he was tortured and when even that failed to bring vast wealth to light, he was accused of being an apostate.

On August 18, 2015, Mr Asaad was led out and beheaded in front of the usual crowd of baying idiots. His body was then tied to a lamp post and his head, still wearing its glasses, placed at his feet. We honour the memory of a distinguished scholar.

height of his power The Bible claims that Solomon conquered Hamath (2 Chronicles 8:3) and went on to build Tadmor in the Wilderness, which is believed to be Palmyra. Whether Solomon actually governed these places or merely reduced their rulers to vassalage is not clear, but the latter is the more likely. Return

fool-proof method Which is, as follows: drive about 5 mph slower than the traffic around you; point your car in the direction you want to go and then go there, ignoring honking horns, waved fists and shouted Arabic. So far, at least, the method has proved successful: the other drivers swirl around you but never actually touch you. Return

no such gold A instant's thought will tell you why. The city of Palmyra gradually withered as trade routes moved or trade failed thanks to the Muslim invasions and the citizens of Palmyra grew impoverished. Any gold they had they either spent or took with them when they finally abandoned the city and moved elsewhere in search of work. Unlike in Egypt, where kings and commoners were buried with store-rooms full of grave goods suitable to their rank, the Palmyrenes were too practical to inter riches with their dead and even if they had, the tower tombs were entered and looted of any valuables long before modern archaeologists arrived. Return

an apostate The evidence of Mr Asaad's apostasy was clear - to an Islamic court, which is to say, to a bunch of fanatical maniacs with no conception of justice. He was charged with having associated with infidels by attending international conferences in his role as Head of Antiquities in Palmyra. He was also charged with being the keeper and preserver of idols - the statues which ISIS have destroyed. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2015