Crude Graffiti

| End of Road | 29 02 41374N 33 26 10.90E | This is as far as you can go by car. It is possible to trace the foot path which heads south and then east from this point. |

| The path | 29 02 04.31N 33 27 06.60E | There is nothing significant about this location apart from the fact that you can clearly see the path to Serabit el-Khadim. |

| Serabit el-Khadim | 29 02 12.37N 33 27 33.68E | The picture is not clear enough to make out more than the general outline of the site. There are ten or so photographs associated with the location and more scattered nearby, apparently at random. |

| Wadi el-Hol | 25 57 00.00N 32 25 00,00E | The location of Wadi el-Hol according to Wikipedia. The coordinates are, I think, very highly approximate rather than exact! |

The earliest settlers in the Sinai appear to have been Egyptian miners, seeking to exploit the region's rich deposits of copper and, curiously, turquoise. According to conventional chronology, these first explorers can be dated to around 5,000 BC and by means of pottery styles archaeologists can trace how they worked their way southwards from one mine to another.

Around 3,500 BC these prospectors discovered the rich veins of turquoise at a place that today is called Serabit el-Khadim and one can only admire their tenacity, for a more desolate and inhospitable location is hard to imagine. Even today visitors are warned to bring plenty of water, as there is none to be had either along the way or at Serabit el-Khadim itself. The mind boggles at the thought of how the ancient Egyptians brought sufficient water to the site for the substantial work force the remains reveal.

The site was first recorded by Carsten Niebuhr in 1762, based, we presume, on accounts garnered from the local beduin. Remarkably, 19th century graffiti show that hardy tourists were seeking it out even then, though it was never a major tourist site. The first archaeological investigation was undertaken in 1905 by Flinders Petrie, who published a report in "Researches in Sinai" in 1906. Subsequent expeditions were mounted in 1935 by Harvard University and during the Israeli occupation of the Sinai (1968-1978). Regrettably the Israelis have not published the results of their excavations, which is the archaeological equivalent of a crime against humanity!

The remains at Serabit el-Khadim are badly ruined and therefore hard to understand. The chief impression the visitor receives is of a random collection of standing stones - round-topped obelisks erected by the miners as memorials. Nearly all of them bear inscriptions in Egyptian hieroglyphics, and some are further decorated with reliefs of traditional Egyptian scenes of the devotee adoring a god, or of the head of the goddess Hathor.

The inscriptions typically record the name of the king who dispatched the expedition, the number of workers and their jobs, and the name of the foreman or overseer in charge of the expedition. There are so many of these inscriptions that the temple has sometimes been called "The People's Temple".

| |

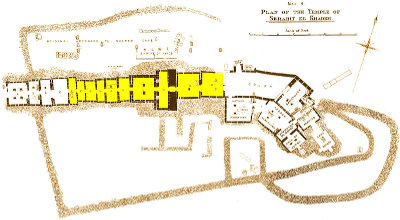

| The plan of the Hathor temple at Serabit el-Khadim. |

One of the buildings identified by Petrie is a typical Egyptian temple consisting of a pylon (or rather, a pair of pylons) facing east, behind which is a small courtyard and behind that the sanctuary. This simple plan is confused by the fact that the earliest temple was some distance to the west, but the very earliest shrine is an underground chapel an equal distance to the east! Just as with the temple of Karnak, whose basic plan is much obscured by the additional pylons and courtyards built by succeeding pharaohs, so the temple at Serabit el-Khadim is made confusing by the addition of two courtyards in front of the pylons and seven sanctuaries behind the first.

It is not clear who founded the temple; the wall which surrounds the sacred area - now heavily restored - was built by Sesostris I of the Twelfth Dynasty and it is reasonable to conclude that the temples were in existence already, as there are no geographical features which would dictate the layout of the wall. The pylon temple was built by Tutmoses III and other parts of the temple were constructed by Amenemhet III of the Twelfth Dynasty and by Hatshepsut and Amenhotep III of the Eighteenth. These later pharaohs are further commemorated by a shrine just to the north of the temple.

Hathor was the patron goddess of miners and from the number of depictions of her head with its cow ears sticking out from under her wig we presume that she was the chief deity worshipped in the temple. However the temple appears to have been built over a sanctuary of Soped, a local deity known as "Lord of the Eastern Desert".

| |

| The entrance to the underground chapel of Hathor at the eastern end of the temple complex. |

The last inscription in the temple is from the reign of Rameses VI of the Twentieth Dynasty, which would indicate that the mines were abandoned after this time, but whether that was because of increasing insecurity in the area or because the mines were no longer profitable we do not know.

What we do know is that in the late Nineteenth Century the British attempted to resurrect the mines - turquoise is still valuable - and caused a certain amount of damage to the ancient remains in the process. However, like the ancient Egyptians, they found that there was not enough turquoise left to be worth the effort and the workings were quickly abandoned.

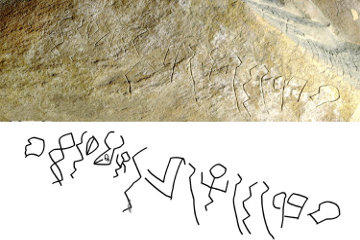

Scattered around the area are further inscriptions cut into the rock faces or cliffs. Some of these are beautifully cut hieroglyphs, clearly created by professional scribes. Among them is an excellent relief showing Pharaoh Sekhemket smiting his enemies. Others are cruder and appear to be the work of the miners. Among them are pictures of boats, perhaps carved by homesick men looking forward to the voyage home, and inscriptions in a script that is almost, but not quite, hieroglyphic.

Petrie was the first to identify this peculiarity of these inscriptions, which use symbols very similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs (though written in a cursive style) but such a restricted sub-set of symbols that Petrie concluded that they were being used as an alphabet. Petrie called it "proto-Sinaitic" and concluded that it was a Semitic language.

| |

| A short inscription in the alphabetic script developed at Serabit el-Khadim |

The date for these inscriptions has been variously assigned to around 1850 BC or 1550 BC (both dates are conventional chronology). The earlier date now appears more likely on the basis of proto-Canaanite inscriptions found in Palestine and, more recently, proto-Sinaitic found at Wadi el-Hol by John and Deborah Darnell.

In 1916 Alan Gardiner was able to confidently decipher a single phrase - lb'lt - which means "to the lady" or "for the lady". As the Egyptian temple at Serabit el-Khadim was dedicated to the goddess Hathor, it was not too difficult to work out that she was the deity being referred to by the feminine form of "Ba'al" - "Ba'alat". Unfortunately work appears to have stalled at that point and no other secure identifications have been made.

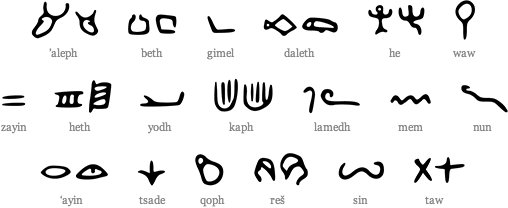

The difficulty is that, according to Gardiner, the inventors of this script used their words to determine the value of the hieroglyphic signs where were in Egyptian. Thus, for example, the Egyptian symbol for "house" - "per" (from which we derive "pharaoh") - was understood by the semitic workmen as "bayt", a word which means "house" in Hebrew or Canaanite. Thus the symbol "per" is used by the workmen to represent 'b'!

| |

| A proposed decipherment of the Serabit script. |

If this theory is correct, then we not only have to decide which hieroglyph any particular sign is based on, but then decide which Semitic word translates that hieroglyph! As not all the hieroglyphs are understood for certain, this poses considerable difficulties for the would-be translator. For example, let us suppose that a particular symbol is believed to be a flamingo, but it is also used for "red" and which of those meanings was used by the inventors of the proto-Sinaitic script? Should it be given the value 'f' (for flamingo) or 'r' (for red)?

In 1932 Romanus Francois Butin, of Catholic University of America, published a detailed study of these proto-Sinaitic inscriptions in the "Harvard Theological Review", based on drawings and photographs brought back by the Harvard expeitions of 1927 and 1930. Although he was able to identify some additional characters, not everyone agreed with his conclusions and no secure translations were proposed.

Most recently Dr Douglas Petrovich, of the Wilfrim Laurier University, Ontario, has proposed a number of other letters, based on the same photographs and drawings. For example, on a stone tablet known as "Sinai 115", which dates to 1842 BC, he claims to have found the words, "6 Levantines: Hebrews of Bethel, the beloved", while another from the same period he reads as "Wine is more abundant than the daylight, than the baker, than a nobleman".

The problem is that these proto-Sinaitic inscriptions are very much graffiti rather than formal inscriptions and it is entirely possible that some bored workman may have scratched such nonsensical scribblings onto a piece of stone. On the other hand, wine is not usually compared to daylight, bakers or noblemen and Bethel is never referred to elsewhere as "the beloved"! I fear that Dr Petrovich's work reminds me of the nonsensical "translations" proposed for other scripts which have not yet been deciphered.

For me, though, the true significance of the Serabit inscriptions is not in what they say but in the fact that they exist. If the Revised Chronology is correct, then they were invented at a time when a certain Hebrew shepherd, an exile from Egypt, was wandering around in the Sinai Peninsula. He must certainly have known of this lonely settlement and may even have sold his sheep to the miners from time to time.

As we know from the Bible story, Moses fled from Egypt in fear for his life, so it is unlikely that he would have gone to Serabit el-Khadim in order to talk Egyptian to the overseers and officials in charge of the work. If he did linger, then he would have sat around a campfire with the Semitic miners and chatted to them in their common tongue - and no doubt sooner or later mention would have been made of the new form of writing they had invented.

We are told that Moses, as a prince of Egypt, was trained in all the wisdom of Egypt, so it is quite possible that he could read and write the cumbersome hieroglyphics. Unlike the professional scribes, however, who doubtless looked down on the workmen's scrawlings, Moses saw their potential and adopted them (or devised his own variation on them) to use as he wrote down an epic poem about the sufferings of Job and then turned to recording the history of the world and of his own people. Some might see this coming together of a new script and a need for a new script as providential - and I would not disagree.

One thing is certain: those critics who, in times past, denied the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch on the grounds that if the mythical Moses was indeed the author we would have to look for a cuneiform or hieroglyphic original, have lost the argument. At the time of Moses (or considerably before Moses if a non-Revised Chronology is maintained) there was an alphabetic script in precisely the area where Moses is supposed to have lived.

Getting there

I have to confess that I have never visited Serabit el-Khadim, but I am told that to reach it you must hire a local guide. He will take you in a 4x4 vehicle as far as possible, but after that you have to walk - or rather, climb, for Serabit el-Khadim is 2,600' higher than the point at which you leave your vehicles (in other words, almost the height of Mt Snowdon in Wales!) I understand that you can approach Serabit from either east or west, with the western route being much the easier, though also much the longer. You can expect the trip to take two or three hours as you climb a long series of steps to the top of the mountain, after which you follow along mountain ridges and the sides of rocky wadis until you emerge on the plateau on which the ruins stand. (The eastern route takes about an hour if you are young and fit.)

Unfortunately the Diggings tours usually consist of older people who would probably have neither the fitness nor the motivation to visit such a remote and insignificant a site. Anyone who would like to visit Serabit el-Khadim these days would be well advised to seek advice from and travel with a reputable local travel agency. There is a continuing Muslim fundamentalist insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula and the safety of lone travellers cannot be guaranteed.

Twelfth DynastyAccording to the revised chronology accepted by this website, Amenemhet III was one of the pharaohs of the Oppression, a fact whose significance we consider later in the article. Return

an alphabet A hieroglyphic script has one symbol per word, so the number of symbols in the script will number many thousands. An alphabetic script, on the other hand, will have between 16 and 40 symbols, from which all the sounds of the language can be created. At the upper end of this range you start to enter what are called syllabic scripts which have between 40 and 90+ symbols.

A hieroglyphic script will have two different symbols for "bat" and "bit", usually pictures associated with those words (and you'd need two different symbols for "bat" - one for a cricket bat and the other for the flying mouse!). The pictures may, like Chinese pictograms, be very highly stylised.

An alphabet script will have four symbols to write those two words - 'b', 't', 'a' and 'i'. The advantage is that you can use those symbols in other combinations to write other words that use the same sounds. For example, "tibia", "tab", or even "tabi" (tabby).

With a syllabic script each each symbol represents a consonant and a vowel (and sometimes consonant-vowel-consonant). Thus you would have different symbols for "ba", "be", "bi", "bo" and "bu", with another set for "ta", "te", "ti", "to" and "tu". Unless you commonly sounded a vowel at the end of words (like the Italians to whom I once tried to teach English and who said "but" as "buta") you would need extra symbols for "bat", "ban", "bap" and "bit", "bin," "bip" and so on. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2017