The Spots on the Dice

Back in 1997 the Diggings team was working at the site of ancient Maresha, which is where we had been digging for a number of years. This particular year we were working in the Roman period bath house and the Israeli archaeologist liasing with our team had asked that some of the team members work at clearing one of the large drains underneath the building.

| |

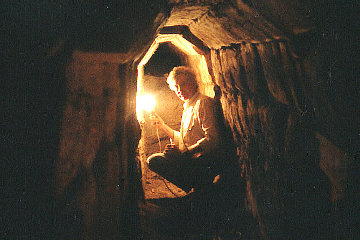

| Keith was one of the team who excavated inside the Roman drain at Maresha. |

Every year at the conclusion of the tour the group split in two. Those who wanted to experience actual archaeological work stayed in Israel for an extra week and formed the Diggings team; the rest travelled to Turkey and explored some of the sites there before returning to Australia. (The diggers didn't miss out; they toured Turkey the following week.)

I had gone with the group to Turkey to show them around and see them safely onto their plane, so it was towards the end of the dig when I returned to Israel and drove to Maresha, where I found the diggers hard at work, including those down in the drain. My father greeted me and showed me what they were doing and how much had been accomplished and then he sort of jerked his head and led me to one side. Wordlessly he pointed to the drain and traced its path to where we were standing, then turned and indicated that I should continue to follow it.

This wasn't difficult: the slabs which covered the drain were larger and set at a different angle to those which made up the floor of the bath house. A few yards further the drain ended in a small room where there was a ruinous but still recognisable toilet. I returned to my father with raised eyebrows and he admitted that he had not dared to tell the diggers the source of the rich brown soil they were excavating!

| |

| Nobody enjoys washing the thousands of pottery fragments found on a dig, but the diggers felt like washing themselves after working in the drain! |

Of course we let them in on the secret at the end of the last day and there was no danger to anyone - after 2,000 years the contents of the toilet had been well composted - but still ...

Archaeologists love rubbish dumps and toilets come a close second. House-proud wives make sure that their homes are clean and tidy, which means that there is little for archaeologists to find, especially if the site has been looted by enemy action or destroyed by a conflagration. However the dish that was accidentally dropped, the comb which has lost too many teeth to be useful, the leather wineskin that has developed a leak and is too old to patch, all end up on the rubbish dump for us to find.

As a quick browse through YouTube will reveal, even today toilets are still receiving valuable items, from iPhones to earrings, cufflinks to loose change - and readers will understand why, in most cases, the erstwhile owner simply shrugs and accepts the loss. If that is the case with a modern toilet, how much more when the toilet is simply a hole in the ground beneath which lies an ordure-filled pit or drain?

And, of course, these days archaeology is about much more than finding objects. A microscopic analysis of the contents of a cess pit or toilet can reveal details of the diet consumed by those who used it, the parasites which infested them - tapeworm eggs are a dead give-away! - and so on.

| |

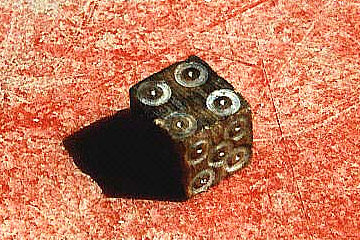

| One of the five Roman period dice found in the drain at Maresha. |

In addition to the objects discarded accidentally, a public toilet may also be the recipient of things whose possession might be an embarrassment to their owner - and such appears to have been the case with the Maresha bathhouse. As report at the time, we discovered five ivory dice. Whether they were dropped down the toilet to evade the police raiding an illegal gambling den or hurled there in anger by a disgruntled gambler, we will never know.

Naturally the dice were examined by everyone on the dig before they were carted off to the museum in Jerusalem (where they probably still reside in a small cardboard box). The fact that the dots on the dice were made of mother-of-pearl inlaid into the ivory was noted. They were measured, weighed and goodness knows what else, but so far as I know, the one thing that wasn't done was to count the dots!

Of course there were six sides to the dice and the dots one to six were all present, but how were they arranged? A modern dice has opposite sides that add up to seven - 1/6, 2/5 and 3/4 - but that is a relatively modern arrangement. In earlier times the numbers were organised to form primes. Thus you would have 1 and 2 opposite each other, forming the prime number 3. 3 and 4 would be opposite each other, as would 5 and 6 and again, both pairs form primes. Even earlier dice do not appear to have followed any particular scheme and the numbers were arranged around the six sides more or less at random.

Whether these different arrangements are thought - or were thought - to contribute anything to the fairness of the dice we do not know. Shape is a more important determiner than the numbers and it is a fact that very early dice could be quite irregular, instead of the perfect cubes with which we are familiar.

It has been suggested that the change from irregular to regular may have come about because the early players considered that the gods determined the way the dice fell. Early Israelites had a penchant for "casting lots" to determine the divine will in various important matters - though it is not clear whether the process involved dice or some other method. Luck or Fortune were considered to be gods or goddesses in their own right. Gradually, however, it dawned on people that the gods had more important things to do than govern the way the dice fell and so ensuring fairness by making the dice perfectly square became vital.

Having said that, there is a way to weight the dice in your favour. You may have come across the expression "loaded dice" or "the dice were loaded against him". Gamblers have been known to carefully drill out the spots on a dice and insert little rods of lead into the holes. Naturally this makes the dice heavier on one side than the other and therefore more likely to fall with that side downwards. There is still an element of randomness, but if a perfect dice will return a 1 exactly 1/6 of the time (provided you do enough throws), a weighted dice may give you a 1 in two out of six throws.

I am told that the way to check whether the dice is loaded is to drop the suspect item into a glass of water. The water slows down its descent and facilitates it rotating so that the heaviest side is downwards. If you get a particular result two or three times in a row, call for new dice!

Which makes me wonder about our system of opposite sides adding up to seven. Let us suppose that you have managed to fill all the dots with something heavy - little lead pellets, perhaps. If the six is opposite the five, the extra weight of a single dot is not likely to make much of a difference. However if the six is opposite the one, you have five extra dots weighing down the dice and making a one more likely! Perhaps the mediaeval dice-makers knew rather more about the laws of chance than we give them credit for.

So here's another line of enquiry which - not unnaturally - we didn't follow: I wonder what is beneath those beautiful mother-of-pearl spots on the dice? If we had levered them out, or better still, x-rayed the dice, would we find that there was something heavy beneath the spots? And if so, we would then be able to say just why they had been dropped down the toilet in Maresha: someone was getting suspicious about just how lucky his opponent was with the dice.

Gambling is a mug's game at the best of time, but when the dice are loaded against you, it's no longer a game. It's robbery, pure and simple.

primes Just in case you have forgotten, a prime number is one that is divisible by itself and one and nothing else. The early primes are 1, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13 and 17. 9 is not a prime because 3x3=9 and 8 is definitely not a prime because 2x2x2=8 and 4x2=8. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2018