Genuine After All?

If you go to GoogleMaps and type in "Hezekiah's Pool, Jerusalem", you will be directed to a rectangular shape. The picture, if you pick the satellite view rather than the map view, is very blurry, which I suspect is deliberate - surely Jerusalem could be shown in better detail? However if you could see it in pin-sharp detail, you would find in the north-east side of the pool a building with two small domes.

| |

| Water does still collect in Hezekiah's pool after heavy rain. Shapira's shop is on the right side of the pool in the furthest corner. |

There are photographs of the pool on the GoogleMaps site, so click on them until you find one looking across the pool towards this building with two small white domes. To the left of it there are two arches - there were originally three - and to the left of these there is a tiled roof projecting out over the pool.

Hezekiah's Pool is a large cistern, allegedly constructed by King Hezekiah when he enlarged Jerusalem to the west as a water supply for the city. If true, it would exclude the legend which also calls this "The Pool of Bathsheba", claiming that this was the very pool in which Bathsheba bathed so as to attract King David's attention. (David, in case your history isn't up to scratch, lived some three centuries before Hezekiah!)

In fact there are good reasons for thinking that the area of the pool was not inside Hezekiah's extended city. To the south of the pool is the east-west David Street, which runs along the bottom of a shallow valley that eventually joins with the upper section of the Tyropoean Valley. Both military sense and the existence of the "Broad Wall" indicate that the north wall of Hezekiah's extension ran along the crest overlooking the David Street valley from the south. As the Herodian and Roman city of Jesus' time lay within the same walls, it means that the area north of David Street, which includes the site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, was outside the city walls. That, however, is another subject.

| |

| Moses Shapira was clearly a man of substance. |

Back in the late 1800s the building with the projecting room was an antiques shop owned by a man called Moses Shapira. Born to a Polish Jewish family, Moses emmigrated to Palestine in 1856 at the age of 25 and, for reasons which are not entirely clear, stopped in Bucharest long enough to convert to Christianity and apply for German citizenship.

Once in Jerusalem, Moses set up shop in the building with the projecting room. The front of the shop opened onto Christian Quarter Road (GoogleMaps knows it by its Hebrew name of Ha Notsrim - the Nazarenes). It was a good location, almost opposite the little lane which leads past the Mosque of Omar and then down a flight of stairs to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. There would have been a constant flow of both tourists and pilgrims and Moses did well out of olive wood crosses and mother-of-pearl brooches.

He also began to dabble in antiquities and Jerusalem Arabs soon found that if they dug up an ancient oil lamp or fairly intact pottery vase, Moses Shapira would give them a good price for it. Soon demand for these antiques outstripped supply and some ingenious person realised that a little hard work and a furnace, followed by over-night burial in soil, could produce as many "antiques" as required. What is not clear is whether Shapira realised that he was selling fakes or not - that is to say, was he the victim of the unknown ingenious person(s) or the instigator?

In 1868 - that is to say, twelve years after Moses arrived in Jerusalem and set up shop - a German missionary called Frederick Klein, came across a buried stone near Dhiban, over in what is now Jordan. After various vicissitudes the stone was bought by a Frenchman called Clermont-Ganneau whose inept - or possibly malicious - interference resulted in the stone being smashed into pieces by its Arab custodians.

| |

| It is believed that this photograph shows Moabite figures for sale in Shapira's shop. |

The interest aroused by the Moabite Stone (otherwise known as the Mesha Stele) did not leave the anquities dealers of Jerusalem untouched and Shapira, with his German sympathies, lost no time in befriending Selim al-Khouri, the Arab who had been responsible for making the "squeeze" of the Stele. Selim had friends in the area of Dhiban who did their own digging and discovered a seemingly endless number of stone or pottery objects and figurines covered in Moabite writing. Shapira was soon doing good business selling the Moabite figures and he particularly favoured German purchasers. The Berlin Museum bought some 1,700 of these objects and with the proceeds Shapira was able to move to a luxurious villa - now known as Tico House after a later resident - in what is now the Israeli New Jerusalem.

There was rivalry - not to say bad blood - between the French and the Germans, which had led to Clermont-Ganneau's bungling interference in the matter of the Mesha Stele. It was gall and wormwood to Clermont-Ganneau's soul to see the Germans stealing a march on his countrymen and this led him to take a closer look at Shapira's figures. It didn't take him long to realise that the "inscriptions" on these objects, although undoubtedly Moabite characters, were a mere jumble of random letters. He jubilantly exposed them as forgeries - and after initial doubts, his conclusion was accepted.

| |

| Professor Christopher Rollston examines a Moabite forgery in the Rockerfeller Museum, Jerusalem. |

Shapira was vigorous in defending the Moabite figures until the weight of public opinion swung decisively against him and then he put all the blame on Selim al-Khouri. Most people accepted his claim to have been the innocent victim of an unscrupulous dragoman, but in view of his previous record of selling forged antiques, there were those who were suspicious - among them Clermont-Ganneau, whose attitude was tinged with both French nationalism and anti-semitism.

Ten years after the discovery of the Moabite Stone, Shapira visited a certain Sheikh Mahmud el-Arakat and conversation over coffee turned to the subject of old inscriptions. Possibly reference was made to the Moabite Stone, which had been broken up and its pieces distributed among the Dhiban Arabs as a charm. The sheikh defended this belief and one of his guests repeated a story that "proved" the efficacy of such old writings.

Some years previously a group of Beduin had been forced to flee - probably following an unsuccessful raid on their neighbours' flocks and herds - and they took refuge in a cave in the side of the Wadi Mujib. There they found several bundles of old clothes and, being Arabs, naturally assumed that they contained a treasure of gold. They ripped off the rags but to their disappointment found only strips of old leather, which they discarded on the floor. However one of their number, recognising that there was writing on the leather, gathered them up and kept them in his tent and in consequence was now become a wealthy man with a large number of sheep.

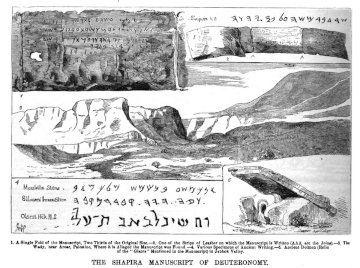

| |

| An illustration from Scientific American's report on the Shapira scroll, showing the Wadi Mujib as well as the scroll. |

It took Shapira five years to track down this lucky Arab and persuade him to part with his talismans, but this time Shapira took the trouble to have the writing translated, to be sure that it was genuine and not just random letters. The ancient scroll turned out to be part of the Biblical book of Deuteronomy, which contained some curious differences from the text as it has come down to us. In particular, there appeared to be an eleventh commandment which stated, "Thou shalt not hate thy brother in thy heart: I am God, thy God".

Shapira seems to have entertained no doubts about the scroll's authenticity, nor of its value. He even spoke of the possibility that it was the original scroll written by Moses! The trouble was, what could he do with it? At some point Clermont-Ganneau became aware of the scroll and asked to see it. Shapira indignantly refused - but that closed off the possibility that the French might purchase it. The Germans - once bitten, twice shy - were also unwilling to make further purchases from Shapira. That only left the British and in 1883 Shapira set out for London, taking the fifteen leather pieces with him. He offered them to the British Museum for a million pounds sterling.

| |

| A lithograph of one of Shapira's scroll fragments, prepared for Christian David Ginsburg. |

The Museum did not have that amount of money and would have to rely upon an appeal to the British public. With that in mind, it persuaded Shapira to allow them to exhibit two of the fragments and there was immediate and widespread interest. Thousands of people flocked to the museum to view these ancient documents, among them the British Prime Minister William Gladstone. Also among them was Shapira's nemesis, Clermont-Ganneau, who peered at them in the glass case and promptly declared that they were forgeries. The undoubtedly ancient-looking leather, he claimed, was cut from the margins of an ancient scroll of Yemeni origins which Shapira had previous sold to the British Museum.

It is just possible that Shapira might have survived Clermont-Ganneau's pronouncement - the British had no particular love for the French either - but a little later the foremost Hebrew scholar in Britian (possibly the world), Christian David Ginsburg, also asserted that the leather fragments were forgeries.

Ginsburg was also a Polish Jew who converted to Christianity at the age of 15. His life's work was the preparation of a critical edition of the Hebrew Bible (the Masorah) and he had, in part, built his reputation by debunking the claims of various manuscripts. For example, he set out to show that the St Petersburg Codex, widely regarded as the original text of the Babylonian rescension, was actually a Palestinian text that had been altered to make it look like the Babylonian.

Unfortunately, the oldest manuscripts with which Ginsburg had to do dated from around AD 1000 and it is not clear what expertise he had in palaeo-Hebrew which would allow him to pronounce definitively on the Shapira Scrolls which may date from as early as 960 BC! There is a suspicion that both he and the Museum experts, who echoed his opinion, were basing their opinion on a belief that it was impossible for leather to survive for so long in Palestine.

Faced with the unanimous rejection of his scrolls and the loss of his hopes for wealth and - perhaps as important - a vindication of his reputation as a scholar, Shapira abandoned London and fled to Holland. There, in the Hotel Willemsbrug in Rotterdam, he shot himself on March 9, 1884.

The first biography of Moses Shapira that I read asserted that the hotel cleaners gathered his effects together and threw out what appeared to them to be worthless pieces of old leather. Wikipedia states that they were, in fact, sold at Sothebys for ten guineas (£10/10/-), but as the British Museum was the seller it is possible that it was only the two pieces that had been on display which were sold.

The purchaser was Bernard Quaritch, a London bookseller, who put the pieces up for sale for £25 - a handsome profit. They were bought by a certain Sir Charles Nicholson, a doctor who had practiced in Australia and inherited his ship-owner uncle's sizeable fortune when he drowned at sea. Nicholson's generosity led to the founding of the Nicholson Museum at the University of Sydney and a mountain in Queensland is named in his honour. Unfortunately Nicholson's house burned down in 1899 and it is believed that Shapira's scrolls were destroyed with it.

However in 2011 an Australian researcher, Matthew Hamilton, put forward the claim that in fact the scrolls were sold to a Dr Philip Brookes Mason - though whether he bought them from Quaritch or Nicholson is not clear. Dr Mason had a substantial collection of curiosities, which his wife sold at auction after his death in 1903, which raises the intriguing possibility that at least some of Moses Shapira's scrolls may still be hiding in an attic somewhere in England!

Ever since the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1948 there has been a sneaking suspicion that perhaps the world was too quick to dismiss Shapira's scrolls as forgeries. We now know that scrolls can survive for thousands of years in the hot, dry climate of the desert. We also know that Bible books are far older than was known in the late 1800s when Shapira was trying to sell his documents. Unfortunately, we will never arrive at a definite conclusion one way or the other until and unless we find at least one of the Shapira scrolls and can subject it to the usual tests - C-14 dating, paleographic analysis, and so on.

Just recently, however, Israeli scholar Idan Dershowitz has claimed that he can prove that Shapira's scrolls were authentic. Dershowitz, at present at the University of Potsdam in Germany, has spent the last couple of years building a database comprising every reference to the Shapira scrolls. These include numerous drawings and transcriptions as well as letters written by Shapira himself.

In one of those letters Shapira describes his attempts to decipher the scrolls, but by comparing his efforts with reproductions of the scrolls it is possible to see that he has made several mistakes. This, says Dershowitz, is evidence that he is not part of a conspiracy to forge; why would he be trying to decipher the text if he already knew what it said? (Of course, it could also be proof that Shapira was highly intelligent and was engaging in a huge bluff in which he pretended to decipher and pretended to make mistakes. Although Shapira was undoubtedly clever and intelligent, it is doubtful if he was quite so clever as all that!)

960 BC This date is based on the style of the letters as transcribed by various artists. Depending on their accuracy, it certainly appears that the scroll is older than the Dead Sea Scrolls, but I must admit that a date in the middle of King Solomon's reign does seem unlikely. Return

© Kendall K. Down 2021