The Temple of Yaho

For once Google Earth has some decent pictures of the area in which we are interested, as well as a lot of photographs, though as usual these are scattered all over the place without any apparent rhyme or reason.

| Elephantine Island | 24 05 05.83N 32 52 08.32E | This is the area of the Jewish settlement behind the temple of Knum. |

| Our hotel | 24 04 53.60N 32 53 13.39E | Note the swimming pool with the cluster of umbrellas on either side. The much enlarged Old Cataract Hotel is just to the north-east. |

| Sahel Island | 24 03 26.44N 32 52 27.56E | The pointer should be over the rocky outcrop where the majority of inscriptions are to be found. |

| Philae | 24 01 30.82N 32 53 03.24E | Actually, this isn't Philae, which is now submerged by the dam. This is the island to which the temples were moved. |

We check in at the hotel reception desk and I hand over the room keys to each member of the Diggings tour. Finally, when everyone else is housed I take my key, pick up my luggage and cross the lobby to the lifts which, I think, must be the slowest lifts in the world. However every journey has its ending and long minutes later the lift shudders to a halt and I step out into the corridor and make my way down to my room. I slip the key in the lock and turn.

|

| The view of Elephantine Island from our hotel. The two pillars mark the Temple of Knum, behind which was the Jewish quarter. |

I put my case on the low table beside the bed, check that the air-conditioning is set as high as it will go, and then step across to the window and draw the curtain to reveal one of the most dramatic and historic views in the world. I step out onto the small verandah, ignoring the heat and lean my hands on the rail. Then I snatch them off again, for the rail is almost hot enough to raise blisters, but all the time my eyes are fixed on the view.

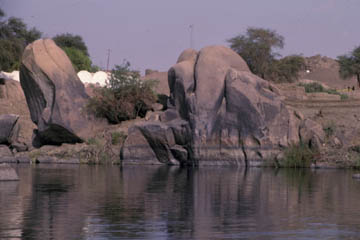

Near at hand is the Old Cataract Hotel, made famous by a scene in Agatha Christie's novel Death on the Nile. In the distance a wall of sand rises up several hundred feet in a sheer cliff that forms a yellow horizon against the pale blue of the sky. Immediately below me the Nile, deep green in colour, flows smoothly between a scattering of red granite islands and ripples over submerged reefs. One of those islands, a quarter of a mile wide and a mile long, is distinguised by water-worn boulders on the river bank that look like herds of mastodons. They give the island its name - Elphantine.

|

| The Old Cataract Hotel, made famous by Agatha Christie's novel, Death on the Nile. |

Here at Aswan the Nile is broken for the first time in its eight-hundred mile course by the First Cataract. In olden times boats wishing to go further south than here had to be towed up the rapids by teams of men hauling on ropes - and many a ship was lost when a rope broke or an unexpected swirl of the current sent it careering into some lurking boulder. Many of these islands were used in pharaonic times by people seeking relief from the burning heat: a couple of miles upstream is the island of Sahel with its many inscriptions pecked into the patina covering the granite while even further south is the famous island of Philae with its beautiful and well-preserved temples.

However it is Elephantine that always draws my eye. The ancient Egyptians called it "Abu" or "Yebu" and claimed that the Nile had its source here - despite the fact that the river quite clearly carries on south for another three thousand miles. Mind you, the priests of Philae made the same claim for their island and with as much truth!

|

| Elephant-like rocks by the riverside, which are supposed to resemble a herd of elephants drinking from the river. |

Elephantine was an important border post between Egypt and Nubia - "wretched Cush" of the inscriptions - and the governor of Syene held a responsible and difficult position. This was the point at which Egypt ended and travellers - merchants, soldiers and government officials - headed south with dread in their hearts, feeling that they were leaving civilisation behind. Many, in fact, scratched their names and prayers for a safe journey into the distinctive eroded rock overlooking the river which is now called "The Rock of Inscriptions".

Modern interest in Elephantine started in 1815 when Geovanni Belzoni bought some ancient papyrii from the locals and that tipped off other collectors to the fact that such things could be found here. In the 1870s the Reverend John Greville Chester came to Aswan and purchased a fine collection of papyrii, many of which he donated to the British Museum in London and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

In the 1890s the German scholar Wilhelm Spiegelberg came here and acquired a collection of papyrii dug up by the farmers of Garb Aswan and when their importance was realised, German archaeologists came and conducted excavations on Elephantine from 1906 to 1908, uncovering the south-west portion of the temple of Knum, the ram-headed god.

|

| Telephoto view of the Temple of Knum, behind which was the Jewish quarter. |

The year after the Germans started work French archaeologists arrived and uncovered the huge courtyard of the same temple. Both groups found what they were looking for: vast quantities of papyrus and ostraca - bits of broken pottery used as note paper in ancient times. The fascinating thing about all this writing, and the reason why it was considered so exciting and important, is that it wasn't the colourful hieroglyphics for which Egypt is famous: these scrolls were written in Aramaic, the language of the Bible!

The story of the Jewish colony of Elephantine is a fascinating one. Unfortunately we don't know all the details but what we can reconstruct is that around 650 BC Pharaoh Psamtik I rebelled against the Assyrians, who had conquered Egypt, and managed to establish his independence. The Assyrians had divided Egypt up into twelve princely states and none of the other princes were willing to submit to Psamtik, so he fought long and hard to overcome them and re-unite Egypt.

Just at this time Judah was ruled by bad king Manasseh, who was pro-Assyrian in his policies and who also persecuted those who worshipped Jehovah, the god of Israel. In much the same way as Muslim religious fundamentalists flock to Iraq and Afghanistan in order to fight against the Americans, so Jewish fundamentalists flocked to Egypt, both to escape persecution at home and to fight against the "Great Satan" of their day - the hated Assyrians.

Psamtik welcomed them with open arms, for he was already employing a large number of Greek mercenaries, and when he expelled the last of the Nubian rulers of Dynasty XXV and drove them back to Nubia, he left a garrison of Jewish soldiers at Elephantine to keep the border safe. The Jewish garrison stayed here, with children following their fathers into the army, right down to 400 BC - two and a half centuries.

|

| The deep excavation which is the presumed site of the Jewish temple. |

As Manasseh's long reign of 55 years seemed never-ending, these Jews despaired of ever seeing the true worship of God re-established in their homeland and so, as soon as they could afford it, they built a temple of their own on Elephantine. It's a pity that we haven't found its ruins, for it was almost certainly a copy of the temple of Solomon in Jerusalem.

Interestingly, like the Bible writers, these Jews had no scruples about pronouncing the sacred name of God, the four letters YHWH whose pronunciation has been forgotten by traditional Judaism. Time and again they refer to or swear by their god, Yaho.

Unfortunately they did not hold to a strict monotheism, for there are also references in the papyrii to the goddess Anath-Bethel and her consort Ashim-Bethel. No wonder the Bible prophets were so strident against the infiltration of heathen ideas and practices into the true religion!

When the Persians conquered Egypt in 525 BC the Jewish mercenaries quickly changed sides and the Persians were only too happy to retreat to their cool hills and leave the mercenaries to carry out the day-to-day governing of the Egyptians. This caused considerable resentment among the Egyptians, who found that their former allies and employees were now ruling over them. However the Jews of Elephantine appear to have made themselves more unpopular than the other mercenaries: they were even unpopular with their fellow mercenaries!

In the year 410 BC Arsames, the Persian satrap of Egypt, was summoned back to Persia for consultations. The priests of Knum promptly bribed the local Persian commander, a man called Widrang, and with his connivance the non-Jewish mercenaries in Aswan crossed over the river to Elephantine and destroyed the Jewish temple. When Arsames returned a few months later the Jews had the satisfaction of seeing Widrang and his son punished and possibly even put to death.

The next step was to have the temple rebuilt and among the papyrii found here is a copy of "A Petition For Permission To Rebuild The Temple of Yaho", dated to 407 BC, which starts off by saying, "Now, our forefathers built this temple in the fortress of Elephantine back in the days of the kingdom of Egypt, and when Cambyses came to Egypt he found it built."

This put Arsames in an awkward position. The Jews clearly had right on their side but on the other hand he didn't want to upset the Egyptians. With true Oriental guile he didn't say "No"; he merely came up with a clever way of shifting the responsibility onto other shoulders and probably preventing the temple being built. He told the Jews of Elephantine that they could rebuild their temple - provided they got permission from Jerusalem.

It was just the luck of the Jewish mercenaries - and possibly Arsames knew this - that at this time Jerusalem was being rebuilt by a different sort of Jewish fundamentalist: Ezra and his colleague Nehemiah. These men had such a narrow view of religion that when the Samaritans, their less strict neighbours to the north, offered to help with the pious task, their offer was rejected out of hand. It was hardly likely that they would respond positively to a request to build a rival temple in Egypt, of all places.

And, of course, they did not. Actually, like Arsames, Johanan the high priest did nothing, and eventually the Jews in Elephantine got the message - but they weren't about to give up. Knowing that the Samaritans worshipped the same God, they decided to write to the Samaritan leader and get his permission to build their temple.

According to the Bible, in the book of Ezra, the Samaritan leader was a man called Sanballat. Some, who chose to regard the Bible as little more than a collection of pious and fictitious tales, were surprised to find that the papyrii found here at Elephantine record that the Jews sent their request to the Persian governor Bagoas and also to the two sons of Sanballat, who had apparently taken over from their aged father!

The Samaritans, never loathe to hurt the Jews, promptly gave permission and the Jews of Elephantine began work on their temple, though Arsames forbade them to offer animal sacrifies, as this was offensive to the Egyptians. The temple was rebuilt by 402 BC, but two years later the Egyptians revolted against the Persians and in the fighting the temple appears to have been destroyed again and the Jews of Elephantine were either wiped out or forced to flee.

This catastrophic end was lucky for us - in the sense that the destruction of Pompeii was lucky for us - for it meant that all their documents were abandoned in the ruins of their homes, to be dug up two thousand years later. We have eleven legal documents from the family archive of a woman called Mitbahiah, thirteen legal documents from the family archive of a man called Ananiah, and the archaeologists found eleven letters and a list of names kept by a man called Yedaniah, plus many other isolted documents and fragments.

Taken together, these ancient documents can just about be considered a commentary on the books of Ezra and Nehemiah; they confirm the historical details presented in those books, they mention many of the characters who feature in those books, they demonstrate that the Artaxerxes of Nehemiah is the first of that name, they clear up many of the questions raised about those books.

For example, some have decried the interest shown in Jewish religious affairs by the decree of Ezra 6, declaring that the Persian kings couldn't possibly be bothered about such finicky little details of ritual, but Elephantine has a parallel in the so-called Passover Papyrus, penned by a Jewish scribe in the Persian chancery.

"To my brother Yedoniah and his colleagues the Jewish garrison, your brother Hananiah. The welfare of my brothers may God seek at all times. Now, this year, the fifth year of King Darius, word was sent from the king to Arsames saying, 'Authorise a festival of unleavened bread for the Jewish garrison'. So do you count fourteen days of the month of Nisan and observe the passover, and from the 15th to the 21st day of Nisan observe the festival of unleavened bread. Be ritually clean and take heed. Do no work on the 15th or the 21st day, nor drink beer, nor eat anything in which there is leaven from the 14th at sundown until the 21st of Nisan. For seven days it shall not be seen among you. Do not bring it into your dwellings but seal it up between these dates. By order of King Darius."

Some scholars developed a theory that the Jews gradually adopted Persian customs and even adapted the Persian religion and so the whole Bible is really just a Jewish version of the Zoroastrian religion. According to this theory, although the Jews started out by calculating their year from autumn to autumn, they gradually adopted the Persian method of spring to spring calculation.

In a wonderful triumph of theory over common sense they claim to have found a problem in Nehemiah where chapter 1 refers to the month Chisleu in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes and chapter 2, ostensibly some time later, refers to the month Nisan, still in the twentieth year. The point is that Nisan is month 1 and Chisleu is month 9. It's a bit like saying, "Well, I came out here in September 2008 and then, a few months later, in January 2008 I returned home."

If the year runs from January to December, that would be pure gibberish, but if the year ran from August to July it would make perfect sense. Anyone with an ounce of sense would see that a spring to spring year doesn't fit the statements in Nehemiah whereas an autumn to autumn one does, but if you are determined to stick to a theory that dennigrates the Bible, fact and sense hardly matter!

The trouble was that for a long time it appeared that the Elephantine papyrii had nothing useful to say on the subject but in 1947 some new Elephantine papyrii turned up - in a tin trunk in America!

Charles Edward Wilbour was America's first Egyptologist. A fascinating man who started his career as a reporter by teaching himself shorthand, he went on to become a lawyer, a translator (he translated Victor Hugo's Les Miserables into English) and finally an Egyptologist. He made many trips to Egypt, where he collected assiduously and also received gifts from other Egyptologists as a mark of their esteem. Among the places where he bought papyrii was Elephantine, which he visited in 1893.

After he died his wife asked their children to give his collection to the Brooklyn Museum, which now houses the Wilbour Library and collection. Unbeknown to them, however, there was part of the collection missing. Wilbour had died in France in 1896 and his belongings were shipped back and stored in a New York warehouse for many years. It wasn't until 1947 that the tin trunk containing a collection of papyrii was identified and turned over to the Brooklyn Museum.

Six years later, in 1953, Professor Emile Kraeling published Papyrus no. 6 of the Brooklyn Museum Papyrii, one of the Elephantine papyrii and the one that settled the dating question in favour of common sense.

Women in the Jewish colony in Elephantine were quite emancipated. One Elephantine papyrus, a marriage contract, says:

"On the 21st of Chisleu... Masheiah ben Yedoniah, a Jew of Yeb... said to Jezaniah ben Uriah... there is the site of one house belonging to me... which I have given to your Mitbahiah, my daughter, your wife... Now I say to you, build and equip that site and dwell on it with your wife. But you may not sell that house or give it as a present to others; only your children by my daughter Mitbahiah shall have power over it after you. If... you build upon this land and then my daughter divorces you and leaves you, she shall have no power over it, in return for the work you have done..."

Notice those words: "my daughter divorces you"! Women could divorce men! This wasn't just a theoretical possibility: Mitbahiah did indeed divorce the unfortunate Jezaniah, married an native Egyptian called Pi, divorced him and then married a certain Ashor. His marriage contract states:

"... I have given you as the bride-price of your daughter Mitbahiah five shekels, royal weight. It has been received by you and your heart is content. Should Ashor die... having no child, male or female, by his wife Mitbahiah, Mitbahiah shall be entitled to the house, chattels and all other worldly goods of Ashor... Should Mitbahiah... stand up in a congregation and declare, 'I divorce my husband', the price of divorce shall be on her head; she shall... weigh out to Ashor seven shekels, but all she brought with her she shall take out and go whither she will without suit or process."

We are shocked sometimes at the ease with which Muslim men can divorce their wives: all they have to do is say three times, in the presence of witnesses, "I divorce you". Well, all Mitbahiah had to do was stand up in the synagogue - I presume that men and women worshipped together - and say "I divorce you" and yet another husband got his chips.

With all this marrying and divorcing and worries about doweries and property rights, marriage contracts in Elephantine were pretty water-tight legal documents - and that means that they had to be dated accurately. The trouble was that there were three calendars in use on Elephantine: there was the Jewish calendar, the Persian calendar and the native Egyptian one. Each had its own names for the months and its own rules for calculating the length of months and years.

Most of the documents bear a single date but some, who wished for added precision, are double dated; that is, they are dated in terms of two calendars, the Jewish and the Persian, for example, or the Jewish and the Egyptian. There are even one or two that are triple dated!

No. 6 is double dated. Only one year is mentioned, the third year of Darius, but the day and month according to the Jewish calendar only match with the Egyptian day and month in one year - July 520 BC - and then only provided that one assumes an autumn to autumn Jewish year.

Now all this is very interesting. As you would expect, it confirms the details recorded in the Bible, showing yet again how reliable that book is. In addition, however, it allows us to introduce an element of precision into the dates mentioned in Ezra and Nehmiah. Before Papyrus no. 6 turned up it was possible for people to argue that the Artaxerxes of Nehemiah was Artaxerxes I or II or even III and critics, who always seem to go for the option that will most discredit the Bible, preferred Artaxerxes II.

As a result of the Elphantine discoveries we now know that the Artaxerxes of Ezra is Artaxerxes I and that the Jews reckoned the years of his reign according to their own autumn to autumn calendar. That means that the seventh year of Artaxerxes, mentioned in Ezra chapter 7, was our year 457 BC and that in turn confirms the prophecy of chapter 9 which gives the very year in which the Messiah would be anointed.

| The Principal Jewish Archives from Elephantine | |||

| Mitbahiah | 11 legal documents | 471-410 BC | A family archive, purchased |

| Ananiah | 13 legal documents | 456-402 BC | A family archive, purchased |

| Yedaniah | 11 letters + 1 list | 419-407 BC | Communal archive, excavated |

© Kendall K. Down 2009