Roman Expenses Scandal

There was a good deal of excitement back in 1973 when excavators working at Vindolanda, a Roman fort along the line of Hadrian's Wall, discovered an ancient rubbish dump behind one corner of the commandant's residence. If you are puzzled by this, pop down to your local rubbish dump - most cities have a public tip where members of the public can dispose of their unwanted objects - and have a look at some of the stuff that is being thrown out. Ancient Romans may not have been as prodigal as modern people in throwing out perfectly good furniture just because fashions have changed, but their rubbish dumps are still treasure troves for the archaeologist.

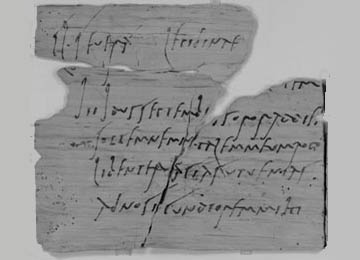

The team, lead by Professor Robin Birley, dug up the usual pot sherds, broken lamps, unidentifiable bits of charcoal and so on. Then someone found a thin sliver of wood and casually brushed the dirt off it. The next moment he was on his feet and shouting for Professor Birley: there was writing faintly visible on the wood!

The area behind the commandant's house had become waterlogged over the centuries and a little swamp had developed. In the anaerobic conditions of the water-logged soil the postcard-sized wooden tablets had been preserved so perfectly that the soot-based ink was still visible. Made of birch, alder or oak, the tablets were between 1mm and 3mm thick, so thin that in many cases the writer had folded the tablet in half so that he (or she) could write the destination address on the back!

|

| One of the Vindolanda tablets. |

The tablets contained a vast amount of the sort of information that archaeologists and historians dream about. Among the 400 so far found there were invitations to parties, requisitions for army goods and supplies, movement orders for troops, petitions for justice and writing exercises by students. Among the earth-shattering revelations in the tablets was the fact that Roman soldiers on the Wall wore underpants and that they referred dismissively to the natives as "Brittunculi" - "little Brits".

Another interesting fact revealed by the tablets was that army units could have individuals on secondments all over the place. Training - either receiving or giving - was the main reason, but providing specialist troops to other army formations was also possible. Builders, medical staff (including vets) and foragers for clay and stone, might all be absent from their parent squadron.

There was a lot of fuss over this treasure trove of information, with appearances on radio and television and interviews in the newspapers for the people who made the find and those involved in conserving and reading them, but like everything else in the media, the furore died down and for some years now there has been no news about them, though they are on display in the British Museum.

In the last week, however, the publicist at Vindolanda has seen an opportunity in the recent scandals involving various members of the British Parliament and their claims for bogus expenses. According to Professor Tony Birley, translator of the wooden tablets, there were hundreds of expense claims, many of them relating to lavish parties held for officers.

"Officers were paid very well - they could buy goods duty free so they would often fiddle expenses by buying items at a cut price then selling them at a profit," he says.

One of the longest letters is from Octavius to his brother Candidus. Among other matters he complains that "I have written to you several times that I have bought ears of grain, about 5000 modii, on account of which I need denarii - unless you send me something, I will lose what I have given as a down payment, and will be embarrassed, so I ask you: send me some denarii as soon as possible." From the wide range of deals Octavius mentions one gets the impression that these two men were rather more concerned with personal profit than with keeping the Picts in their place.

He concludes his letter with the information that "I hear that Frontinius Julius has for sale at a high price the leather goods which he bought here for five denarii each!"

In other words, there is nothing new under the sun. Human beings will seek dishonest gain whenever they see an opportunity and whether we are talking about Roman centurions or British parliamentarians, the motives and the methods bear a depressing similarity. All the more credit, therefore, to those few upright individuals who keep aloof from the surrounding morass of self-seeking corruption.

© Kendall K. Down 2009