A Modern "Ship of Punt"

Back in 2005 archaeologists working on the Red Sea coast of Egypt made a surprising discovery. Kathryn Bard, associate professor of archaeology at Boston University, and Chen Sian Lim, one of her students, were clearing sand away from a cliff face in the side of Wadi Gawasis, near Egypt's Port Safaga. An Egyptian archaeologist had suggested that the site held the remains of the Egyptian port of Saaw, the starting point for expeditions to the land of Punt.

They had only been working for an hour or so when the sand wall collapsed to reveal a fist-sized hole. With her eyes blinded by the harsh sunlight reflected from the burning sand, Kathryn cautiously put her arm into the hole and was astonished to discover that it was no mere animal burrow but a gaping chasm. A few more blows with the shovel enabled the pair to squirm into what turned out to be a 70' long, curiously rectangular cave. Littering the floor were coils of rope, planks of wood and a couple of wooden boxes in which Egyptian hieroglyphs were painted.

Kathryn and Chen were members of a team that included Egyptologists from Florida State University and the University of Naples as well as Boston University. When Kathryn and Chen re-emerged from the hole and starting calling people came running and soon many pairs of hands were at work clearing away the sand. Not only did they completeley uncover the entrance to the first cave, but they also found the entrance to a second - and this entrance was clearly man-made, for it was made of limestone blocks and baulks of timber!

Further work in the area uncovered several limestone stele, one of which bore the cartouche of Pharaoh Sesostris III. This which placed the caves and the objects they contained towards the end of the Middle Kingdom - and that meant that they were nearly 4,000 years old! Later on in the year the team brought ground-penetrating radar and with its help uncovered another five caves, making seven in all.

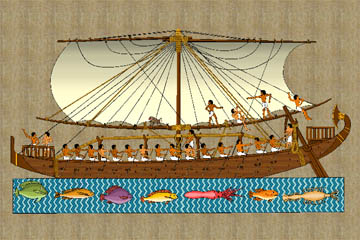

When the team came to examine the caves and their contents they were startled to find sixty ropes, neatly coiled and tied in the middle just as sailors store rope today. Each rope was about 98' long and extremely heavy - so thick and strong that the archaeologists came to the conclusion that these had a special function. Much thinner ropes would suffice for raising and managing the sails of an Egyptian ship or for tying its boards together, but depictions of Egyptian sea-going vessels show that they have a heavy rope running from stem to stern. Known as a "hogging truss", the rope stops the vessel sagging at the ends when a wave lifts it in the middle.

Somewhat more puzzling was the rope itself, for early analysis showed that it was not made of halfa grass, papyrus or palm fibre. The suspicion is that it is made of some type of reed, but the species of reed and the reason why that should be used rather than the more common materials is not known.

The caves contained a number of heavy stones with a hole bored through at one end, the ancient anchor. There was also a deal of pottery, some of which was unfamiliar to the team but which was later identified as coming from eastern Sudan, Eritrea and the Yemen.

Even more startling than the caves and the ropes were the two wooden boxes, for they not only bore the cartouche of Amenemhet IV, but the inscriptions further stated that their now vanished contents were "Wonders of Punt"! A second stele bore the name of Amanemhet III and referred to two expeditions to Punt and named the expedition leaders: brothers named Nebsu and Amenhotep.

The conclusion was irresistable: this was the Egyptian naval base from which expeditions to Punt were sent out and the caves and their contents were the remains of a naval workshop. Even back in pharaonic times the Red Sea shore was a desolate place with no trees for timber. The ships which went to Punt were brought as planks down the Nile to a point opposite Wadi Gawasis, then carried overland for ten days to these caves where they were assembled, just like the modern reassembly of Khufu's boat which stands behind the Great Pyramid.

Not only was wood scarce and expensive in Egypt, but on the Red Sea coast it must have been like gold dust. That was why these great caves were dug into the cliff, to protect the precious wood against the elements and against beduin who, from their camps out in the desert, must have viewed all this timber with covetous eyes. A single plank, stolen from the assembly site, could have provided tool handles and tent poles for a whole tribe - but the loss of that same plank could have jeopardised an entire year's trading as men set off across the desert to find a replacement for the ship's keel or hull.

It wasn't only assembly, however. When the ships came back from Punt they could not be left to the tender mercies of wind and weather. Instead they were dragged ashore, taken apart and stored back in the caves where timbers riddled with shipworms could be noted and replaced. (The discovery of wood so affected is evidence that the voyage to Punt must have taken several months, perhaps as many as six.) In addition, as Khufu's boat shows us, the timbers were held together by tightened ropes which were undoubtedly damaged by the working of the ships in the waves of the open ocean and further weakened by exposure to sea air and damp. The ropes too had to be examined and replaced where necessary. Some of the Wadi Gawasis timbers, however, bore traces of being held together with copper straps. These may have been more resistant to water damage than fibre ropes, but they too would be damaged by the working of the ships in rough seas.

All this required a work force of several thousand men and the excavators, clearing the ground between the caves and the sea, were delighted to discover hundreds of clay moulds in which bread was baked, to provide food for the workmen and sailors of the naval base. Inscriptions indicate that up to 3,700 men were involved in the work of transporting, assembling and manning the fleet of five or six "ships of Punt".

Curiously, although New Kingdom pharaohs - including, famously, Queen Hatshepsut - used Saaw for their own expeditions to Punt, the caves were last used during the Middle Kingdom. It is likely that trade with Punt was interrupted as the Twelfth Dynasty collapsed and the Hyksos invaded the land. By the time Egyptians returned to Saaw the caves were buried under drifting sand and the secret of their existence had been forgotten.

Once the discovery hit the headlines creative people in the media began to consider how to exploit it for their own profit. The National Geographic, of course, made a documentary about it, but it was the French production company Sombrero and Co. who came up with the most original idea. They donated $200,000 and asked Cheryl Ward, anthropologist and principal investigator for maritime archaeology on the team, to oversee the recreation of a Punt ship and its voyage.

A good deal of research had to be done to make the best use of the opportunity. The first problem was the timber: ancient Egyptians used cedars from Lebanon, but even if the ancient port of Byblos had been active, there was no way that Ward could repeat the anguished journey of Wen Amun - the few remaining cedars are highly protected and there is no way she would have been allowed to cut any down. The best substitute turned out to be Douglas Fir.

The next step was to use the template of the Khufu boat and the evidence of the timbers uncovered at Wadi Gawasis to design the ship and in this she was helped by the university Master Craftsman Programme to build scale model ships so that she could be sure of the size, shape and lay-out of the planks. In October 2008 the full-size replica was finished, no frames, no nails, and planks that were fitted together like a jigsaw puzzle. Christened "Min of the Desert" - Min was the Egyptian god of the eastern deserts - she was launched on the Nile to give the timbers a chance to absorb water and swell shut around the joints. The calm waters of the Nile also gave the crew a chance to get used to handling the rigging, oars and steering of their 66'x16' craft.

Reproduction only goes so far, however. Both the researchers and the film crew baulked at the idea of taking their creation apart and carrying it 100 miles across the desert to the Red Sea. Instead they whistled up an Egyptian low-loader and the complete ship was carried off to Port Safaga at thirty miles an hour. (I trust that the vicious little speed humps to which the Egyptians have lately become addicted were removed, otherwise the vessel, no matter how stoutly tied together, must infallibly have fallen apart in the first thirty miles.)

The 24-person crew also baulked at the prospect of facing a peril of which Hatshepsut never dreamed - Somali pirates in fast boats and armed with heavy machine guns. Captained by Professor David Vann, assistant professor of English at Florida State University but also expert sailor, "Min of the Desert" set sail in late December 2008, heading south. The crew were surprised to discover that their ancient boat, powered by nothing more than a square sail, skipped over the water at a spritely 6 knots; at that speed the voyage to Punt - assuming that it was indeed in Somalia - would have taken little more than a month with another two months for the return journey. After a mere week and 150 miles, however, "Min of the Desert" had to put in to shore to where the low-loader was waiting at the Egyptian border.

Although far short of what the ancient Egyptians had accomplished, Cheryl Ward feels that it has been a valuable exercise.

"When it was time to raise the sail and point our bow south toward the land of Punt, we had only our crew and human energy to rely on. Whether standing and rowing over the rail, hauling on a line to hoist the sail without the help of pulleys or keeping track of our progress along the shore, we all felt connected to those ancient sailors on their epic voyages."

© Kendall K. Down 2009