Fingerprints at Mizpah

Tel en-Nasbeh, an archaeological site 8 miles north-west of Jerusalem, was excavated between 1926 and 1935 by William F. Badé of the Pacific School of Religion in Berkley, California. Badé, a naturalist and self-taught archaeologist, used the most up-to-date archaeological techniques in his work. He divided the site up into 10m squares which he cleared in strips, filling each completed square with spoil from the next (which was fine for archaeology but hopeless for tourism!)

|

| Professor William F. Badé excavating at Tel en-Nasbeh. His dignified suit would hardly be thought suitable garb for archaeology these days! |

He also kept meticulous records of his work, drawing plans, taking photographs and describing each find - about 23,000 of them - on individual file cards that included scale drawings. It was a tragedy that he died in 1936 and was thus unable to write up his excavation, a task that was completed by his colleagues, Chester C. McCown and Joseph C. Wampler. W. F. Albright, doyen of Palestinian archaeology, wrote Badé's epitaph:

He was easily the most versatile man who has ever been attracted to the field of Palestinian archaeology, and all who came in contact with him fell under the spell of his personal charm. His passing is a great loss to each of the many spheres of life in which he was an outstanding figure.

The excavations at Tel en-Nasbeh uncovered a small village that was first settled in the Late Chalcolithic. The village remained inhabited into the Early Bronze I period, but after that it was abandoned for some 1,500 years until Iron Age I, when it became a large agricultural village.

|

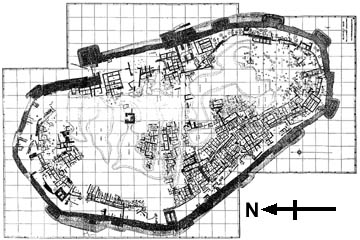

| Map of Tel en-Nasbeh during the Iron II period. Note the thick wall that surrounded the town and the gateway in the north-east quadrant. |

In Iron II the village was surrounded by a wall 2145' in circumference and 13' thick and fortified by a massive gate, probably because of its position on the frontier between the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. Badé linked that discovery to a story recounted in the Biblical book of Kings.

There was war between Asa and Baasha king of Israel throughout their reigns. Baasha king of Israel went up against Judah and fortified Ramah to prevent anyone from leaving or entering the territory of Asa king of Judah.

Asa then took all the silver and gold that was left in the treasuries of the LORD's temple and of his own palace. He entrusted it to his officials and sent them to Ben-Hadad son of Tabrimmon, the son of Hezion, the king of Aram, who was ruling in Damascus. "Let there be a treaty between me and you," he said, "as there was between my father and your father. See, I am sending you a gift of silver and gold. Now break your treaty with Baasha king of Israel so he will withdraw from me."

Ben-Hadad agreed with King Asa and sent the commanders of his forces against the towns of Israel. He conquered Ijon, Dan, Abel Beth Maacah and all Kinnereth in addition to Naphtali. When Baasha heard this, he stopped building Ramah and withdrew to Tirzah. Then King Asa issued an order to all Judah—no one was exempt—and they carried away from Ramah the stones and timber Baasha had been using there. With them King Asa built up Geba in Benjamin, and also Mizpah.

1 Kings 15:16-22

The location of Tel en-Nasbeh led Badé to identify it with the Mizpah mentioned in this passage, an identification that has stood the test of time. It is particularly significant that a new stratum was identified in the Babylonian period, and the Bible tells us that Mizpeh was the location of the short-lived quisling government of Gedaliah. In this stratum new buildings were erected over the ruins of the Iron II town, larger and finer than the preceding structures.

Perhaps the most significant difference was that during Iron I and II the dead were buried outside the town, but in the Babylonian period the dead were buried in bath-tub shaped coffins inside the dwellings, a Mesopotamian practice.

Following the Persian period Tel en-Nasbeh was deserted once again, though Greek, Roman and Byzantine pottery indicate that there was still settlement in the area, though probably scattered farm houses rather than a village. A Byzantine church was identified as well as tombs from the same period.

Unfortunately the publication of Badé's excavations was poor. The two men who undertook the work were unfamiliar with archaeology; McGowan was a New Testament expert and had only visit the site once, Wimpler was called up in the Second World War and had to rush his contributions before joining the army. The financial constraints of the Depression also played a part in limiting the work done on the report.

Perhaps more significant than either of those factors was the fact that Badé's work was pioneering and many of the features that are now familiar to us were new and unrecognised by him. The four-room house, now believed to be typical of Israelite architecture, had never been encountered before and was interpreted as a temple. Olive presses were thought to be dying installations while rock-cut wine presses were an unrecognised puzzle.

However Badé did come up with one technique that I haven't heard of elsewhere. The largest concentration of Early Bronze pottery came from the north-west corner of the tel, which may have been the centre of the village, but there was some dispute over the styles of the pottery, whether they all belonged to the same stratum or should be assigned to different strata. There was also the problem of pottery found in the tombs some distance from the tel. Badé happened to look at the pottery out in the sunlight and recognised that the fingerprints of the ancient potters were still visible in the clay! He was able to use fingerprint evidence to interpret the pottery evidence and demonstrate that the same potters were involved in both sets of pots.

© Kendall K. Down 2009