Palermo's Neglected Stone

I can never claim to be a mathematician - I make too many silly mistakes to ever be trusted with calculating the compound interest on a bank account or the trajectory of a rocket heading for the moon - but nonetheless I am interested in numbers. I've read books about Pi, Fermat's Last Theorem, chaos theory and all sorts of other arcane subjects. I also have a fascination for the subject of chronology, which is why, when the Diggings Tour visited Sicily in 2007 I made a bee-line for Palermo Museum and its famous stone.

Much of Egyptian history depends on king lists - lists of kings together with details of their reigns, drawn up by priests. The most famous of these king lists is that of Manetho, even though it is the only one which has not survived! All we have of Manetho are quotations from his book in Josephus and Eusebius. Other king lists have come down to us carved on stone: the Abydos King List, the Saqqara King List, and so on. Of them all, the Palermo Stone is one of the most detailed and also the most neglected.

I had seen photographs of the Palermo Stone, of course, but I was not prepared for the small, rather shabby piece of stone housed in a revolving glass case hanging from a wall in the courtyard of the museum. I thought that at the very least such an important relic would be inside the building, surrounded by bullet-proof glass and electronic eyes to guarantee its security. Instead, it was in a quiet alcove screened from passers-by and five minutes work with my Swiss Army knife and I could have slipped it into my camera bag and made off with it. To say that I was apalled and disgusted is understatement.

|

| The Turin Museum places its replica of the Palermo Stone in a substantial glass case. |

One reason why it is not so valued, perhaps, may lie in the fact that no one knows where the stone comes from. It was acquired in 1866, in the days when such objects were curiosities in their own right and no one thought to worry about provenance. Even less were people concerned at splitting up such items, and when other parts of the same inscription were offered for sale in 1895 and 1963 the Palermo Museum didn't bother to bid for them, so they ended up in the Cairo Museum and the Petrie Museum in London.

Yet the value of the stone for the chronology of Egypt cannot be over-estimated, for it consists of a number of vertical columns, each one headed with the name of a king, with a separate column for each year of his reign and details of what happened and the height of the Nile in that year. The earliest kings mentioned come from the pre-Dynastic period and the latest are from the Fifth Dynasty. Beginning with Heinrich Schofer in 1902, thirteen major studies have been conducted on the Palermo Stone, which fall into two camps. One group accepts the Palermo Stone as a genuine historical document, the other views it as political propaganda intended to portray the chaos before Menes unified Egypt. In this view the pre-Dynastic kings are mere myths and of no historical value. (It's odd how scholars, in their conceit, are so ready to dismiss ancient records as "myths" and of no historical value!)

With any luck, however, the Palermo Museum will be according its star exhibit a bit more respect in future, because archaeologists now know that fifteen of the pre-Dynastic kings it names were actual historical characters whose existence is proven by contemporary inscriptions found in Egypt. Once we accept the historical character of the Palermo Stone, then we can begin to use its data to recreate the history of early Egypt.

Dr Toby Wilkinson of the University of Cambridge fired renewed interest in the as a result of a paper presented to the International Egyptology Conference in London back in 2000. He had the distinction of being the first scholar to examine all seven extant fragments of the original Royal Annals, which must have been about 7' long and 4.5' high before it was broken up.

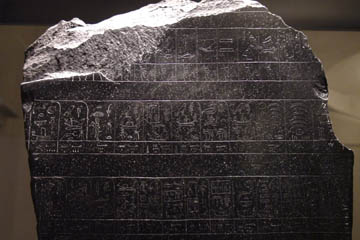

|

| Detail of the hieroglyphs on the Palermo Stone. |

The Palermo Stone is divided into horizontal sections (called "registers") which are further divided into vertical columns or boxes. Each box is divided into two: the upper part contains the name of the pharaoh and the number of years for which he reigned, below which are brief notes of important events of the pharaoh's reign, which include various religious ceremonies, the biennial counting of the cattle and significant events such as buildings completed, statues erected and wars undertaken. The lower part is a record of the height of the Nile flood, the Inundation, on which Egypt's prosperity depended. Judging by the size of these boxes and the estimated size of the original stone, there must have been hundreds of kings listed.

From the details on the stone and the details we find in Manetho, it would seem that this was one of the records which he consulted when making his list of the dynasties. The scholars who disapprove of the Palermo Stone have used this as an excuse to cast doubts on Manetho as well.

Once we accept that the Palermo Stone is a genuine historical document and not merely meaningless boasting, we can use the data it contains to gain a more detailed picture of life in pre-Dynastic Egypt. To our surprise we discover that the pharaohs travelled widely and frequently, leading expeditions into Nubia that brought back 7,000 slaves and 200,000 head of cattle; more peaceful expeditions headed forthe turquoise mines of Sinai or went on trading trips to PUnt that brought back 80,000 measures of myrrh, 6,000 of electrum, 23,020 of unguent and 2,900 logs.

In other words, the pre-Dynastic Egyptians were a vigorous, adventurous people with a thriving industry of copper smelting and with the culture and resources to undertake difficult journeys for trade and conquest.

Many of the events mentioned on the Palermo Stone and the other fragments were of a religious nature and the most intriguing of these are references to the king creating various gods such as Sheshat, Min and Anubis. It would seem that the king would visit a town or city and there erect a temple and cause an image to be carved, then he would proclaim the name of the god and give an indication of its attributes. These events were recorded as "the birth of Min" or "the birth of Anubis". Irrespective of the myths that later grew up about how the gods created the world and man, here we have evidence for man creating the gods.

Indeed, it goes further than that. By providing temples, priests and offerings, the king was doing the gods a favour, without which their worship would cease and their names be forgotten - the ultimate disaster for either god or human. This is why, in the Pyramid Texts, many of which are pre-Dynastic in origin, the king boasts that he "bestows power and takes away power and there are none that can escape".

No wonder pharaoh found it so hard to swallow Moses' demand that he submit to a God Whom he had not created.

© Kendall K. Down 2009