Vegetarian Gladiators

The discovery of 67 bodies in a cemetery where the tomb reliefs depicted gladiators continues to excite archaeologists and historians. All 67 skeletons are male and show signs of fatal injuries, mostly to the head, so these are unlikely to be men who died of old age!

The bodies were found in Ephesus, buried in a 200' square plot along the road that led from the Magnesian Gate to the Temple of Artemis

The bodies were found at Ephesus, where the Austrians have been excavating for nearly a century. As a result the skeletons were handed over to Karl Grossschmidt of the Medical Univerity of Vienna and Fabian Kanz of the Austrian Archaelogical Institute for investigation. Using CT scaning and microscopic analysis of damage to the bones, the two men have been conducting forensic investigations to try and determine the cause of death.

|

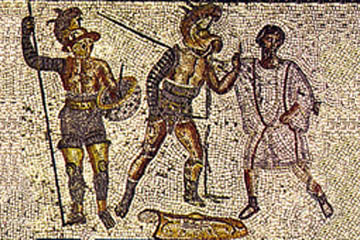

| A referee stands in the background while two gladiators fight. The man with the raised finger appears to be asking for a decision - the fact that he has dropped his shield and has no weapon indicates that he is the defeated man appealing for a "thumbs up". |

The first conclusion to emerge from the study is that the gladiators fought "by the book". There was little evidence of multiple serious injuries or mutilation, which would indicate that when a man was badly injured the fight stopped. Ancient records make mention of referees and depictions of gladiatorial combat occasionally show an unarmed figure in a toga somewhere in the background with an arm raised - almost certainly the referee declaring the winner or stopping the fight.

On the other hand, a high proportion of the wounds were to the head, which was interesting in view of the fact that all gladiators, with the exception of the lightly-armed retiarius, wore helmets. Three of the skulls had triple wounds from the trident of a retiarius, which is impressive considering that the usual opponent of the retiarius - who was armed with a trident and a net - was a murmillo who had a sword, a shield and was protected by a heavy bronze helmet with tiny eye slits. Nimbleness clearly won out over massive but ponderous protection.

On the other hand, four skeletons had deep cuts in their shoulder blades which Grossschmidt interprets as stab wounds into the heart while the victim was lying face down, either incapacitated by other wounds or tripped up in the heat of conflict. Several others had cuts on their upper thoracic vertebrae, indicative of stabbing down through the shoulder into the heart. Presumably these men had been wounded and then had their appeals for mercy refused - the traditional "thumbs down". As they knelt on the sand their executioner approached from behind and thrust down into the unprotected area between neck and shoulder, producing near instantaneous death.

Heavy sums were bet on gladiatorial fights, particularly if a favourite was involved, and the temptation to "throw" a bout must have been strong - but what financial inducement could weigh against death? You might be willing to "take a dive" and clean out the bookies, but only if you were around to enjoy the winnings. In the early days this had happened more than once and the injured fighter, well rewarded for his obliging loss, would be retired or sent off to fight in the provinces while the trainer or the bookies - whichever had organised the sham fight - banked the loot.

By the second century AD, which is the period of this cemetery, steps had been taken to preserve the "purity of the turf". A dead fighter could be assumed to be the genuine loser in the combat, but one who was merely badly injured - or appeared to be badly injured - might recover. In order to ensure that no one faked death, at the conclusion of a fight an arena official dressed as Charon, the ferryman of the Underworld, marched on accompanied by slaves carrying a brazier in which a couple of branding irons were heating. A body that didn't react when prodded with a red-hot iron could be assumed to be genuinely dead.

If the body twitched, however, Charon signalled to his attendants and the unlaced and removed the fighter's helmet. Charon then hit him on the side of the head with a hammer, ensuring that he was well and truly dead and all bets could be paid out in safety. Ten of the 67 skulls found had square holes in the side, indicating that they had twitched at the wrong moment. (Of course this was also a coup de grace as medical treatment for seriously injuries was at best rudimentary and painful and at worst merely prolonged the victim's existence in agony until he died of blood loss and infection.)

As well as looking at the external appearance of the bones, Kanz and Grossschmidt also subjected them to isotopic analysis, which reveals the chemical make up of the substance analysed, revealing trace elements like calcium, strontium and zinc. Surprisingly, the evidence from the bones shows that the ancient gladiators were not fed on meat, nor even on a meat-rich diet. Rather they, like most of their contemporaries from the poorer classes, ate a vegetarian diet, high in carbohydrates and occasionally supplemented with calcium.

The puzzling thing is that gladiators were not among the poor classes! Even if they didn't earn much, being slaves - though some gladiators became quite wealthy - their owners and trainers, like the owners and trainers of boxing and wrestling stables today, would have ensured that they received the best diet for strength and endurance.

This finding should not have been too much of a surprise. Ancient accounts of gladiators sometimes refer to them as "barley men" - and barley appears to have been priminent in the diet of those studied by Grossschmidt and Kanz. Grossschmidt speculates that fat - or at least, well-padded - gladiators made for a more spectacular show. Not only would a good layer of fat protect the fighter's vital organs such as nerves and important blood vessels, but such a non-mortal injury would provide the blood and gore that turned spectators on.

A purely vegetarian diet, however, is not particularly rich in the calcium needed to build strong bones and we know from ancient records of gladiator training that charred wood and bone ash, which are rich in calcium, were included in the fighters' diets. Neither rate high in the gourmet stakes, but I suppose that if your life is at stake you might do worse than gnawing on a charred stick. The results certainly warrented the gastronomical outrage, for calcium levels in the skeletons were "exhorbitant" compared to those of the general population.

© Kendall K. Down 2009