Balbila's Art

Ancient poets such as Horace and Ovid have, of course, been the bane of schoolboys' lives for countless generations. Less well-known are the women poets of antiquity — indeed, the only name that springs to mind is Sappho, a Greek poetess of the sixth century BC — though if modern times are anything to go by, women are not backward when it comes to rhyming "moon" with "June". Of course, women have had to face the usual prejudice against their sex which led many of them to publish under male pseudonyms.

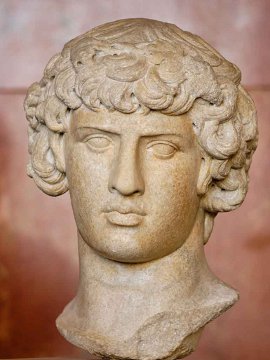

There is, however, one female poet whose name is familiar and whose works are well-known to all scholars of antiquity. In AD 130 the Roman emperor Hadrian, who visited every part of his vast empire, undertook a tour of Egypt and sailed up the Nile at least as far as modern Luxor. Among the crowd of secretaries, generals, cooks and bodyguards who accompanied him were two people whose occupations were strictly non-governmental. One was Antinoüs, an extraordinarily handsome youth in whom Hadrian took a decidedly non-paternal interest. The other was Julia Balbilla, a poetess. Both were to leave their mark on history.

| |

| Antinous, Hadrian's favourite, who was drowned in the Nile after falling overboard. |

The story of what happened to Antinoüs is a little confused. One version goes that he leaned over the side of the boat in order admire his own reflection in the water, the other holds that he was trying to catch the reflected moon. In either case, the unfortunate (and probably tipsy) young man leaned too far and toppled into the water. Needless to say, he could not swim and Hadrian was inconsolable at his loss. The obsequious Egyptians promptly earned imperial gratitude by declaring that Antinoüs had been taken by the Nile god in order to keep him company, which bestowed a certain aura of divinity on Hadrian's favourite. Statues of various gods were erected on Hadrian's orders, all bearing Antinoüs' features, temples were dedicated to him and archaeologists frequently come across the familiar face on a statue erected by some provincial town eager to win imperial favour. At the site of the accident, 26 miles south of al-Minya, Hadrian founded a city named, inevitably, Antinoöpolis. As the start of the Via Hadriana, a short-cut from the Nile valley to the Red Sea, Antinoöpolis enjoyed a certain degree of prosperity for several centuries.

The event was, of course, commemorated by Julia Balbilla in her most florid verse. It is, perhaps, fortunate for her reputation that her lament has not been preserved. Posterity has been harsh enough on what has survived, claiming that the work is trite, servile and barely worthy of the term doggerel. That it has survived at all is due more to what she wrote on than on what she wrote.

Naturally the locals were keen to show off all local attractions to their august visitor and chief among the charms at Luxor were the speaking statues of Memnon, two colossii standing in solitary splendour among the crops on the western bank of the Nile. Each morning, as the sun rose, the right-hand statue hailed almighty Ra with a loud, harsh screech and crowds of the devout and the curious gathered before dawn to witness the supernatural event. Among them came the emperor Hadrian and his entire entourage.

To the emperor's immense gratification, he had barely arrived in the pre-dawn darkness when the statue spoke, quite obviously greeting him. It spoke again when the sun rose and a little later, when Hadrian was preparing to depart, it spoke for the third time, bidding him farewell. Such an auspicious event, quite obviously, had to be suitably commemorated and Julia Balbilla stepped into history by producing three extempore poems which received general applause and some handy craftsman did some nifty work with a hammer and chisel and carved her words in elegant Greek letters on the statue's leg — which was as high as he could reach on a ladder without waiting for scaffolding.

There Julia Balbilla's words remained, a vulgar curiousity to tourists and a perpetual reminder of the folly of graffiti artists who deface the beauties of nature and art with their incoherent and irrelevant scribblings. A recent collection of women poets through the ages has, mainly because of their scarcity, prompted a re-evaluation of Julia Balbilla and somewhat to the surprise of many, the verdict has been in her favour. Her rhymes are conventional rather than daring, her scansion is correct, her language is elegant and if her subject matter does not quite reach the sublime heights of others, well, she is not the first to have been obliged to prostitute art in the service of a wealthy patron.

Epigram by Julia Balbilla carved on the legs of the Colossi

Memnon the Egyptian I learned,

When warmed by the rays of the sun,

Speaks from Theban stone.

When he saw Hadrian, the king of all, before rays of the sun

He greeted him - as far as he was able.

But when the Titan driving through the heavens with his steeds of white

Brought into shadow the second measure of hours,

Like ringing bronze Memnon again sent out his voice

Sharp-toned; he sent out his greeting and for a third time a mighty-roar.

The Emperor Hadrian then himself bid welcome to

Memnon and left on stone for generations to come

this inscription recounting all that he saw and all that he heard.

It was clear to all that the gods love him.

When with the August Sabina I stood before Memnon

Memnon, son of Aurora and holy Tithon,

seated before Thebes, city of Zeus,

Or Amenoth, Egyptian King, as learned

Priests recount from ancient stories,

Greetings, and singing, welcome her kindly,

The august wife of the Emperor Hadrian.

A barbarian man cut off your tongue and ears,

Impious Cambyses; but he paid the penalty,

With a wretched death struck by the same sword point

With which pitiless he slew the divine Apis.

But I do not believe that this statue of yours will perish,

I saved your immortal spirit forever with my mind.

For my parents were noble, and my grandfathers,

The wise Balbillus and Antiochus the king.